On August 14, 2024, one of the greatest moments of civil aviation took place 105 years ago: the first time a mail sent from land was delivered to the deck of a ship navigating on the high seas by aircraft. With this experiment, a decade-long process has come to an end, and it has been proven that combined air-sea mail delivery by plane is possible. In my latest article, I recall the details of the successful experiment and the series of events that started the process leading up to it.

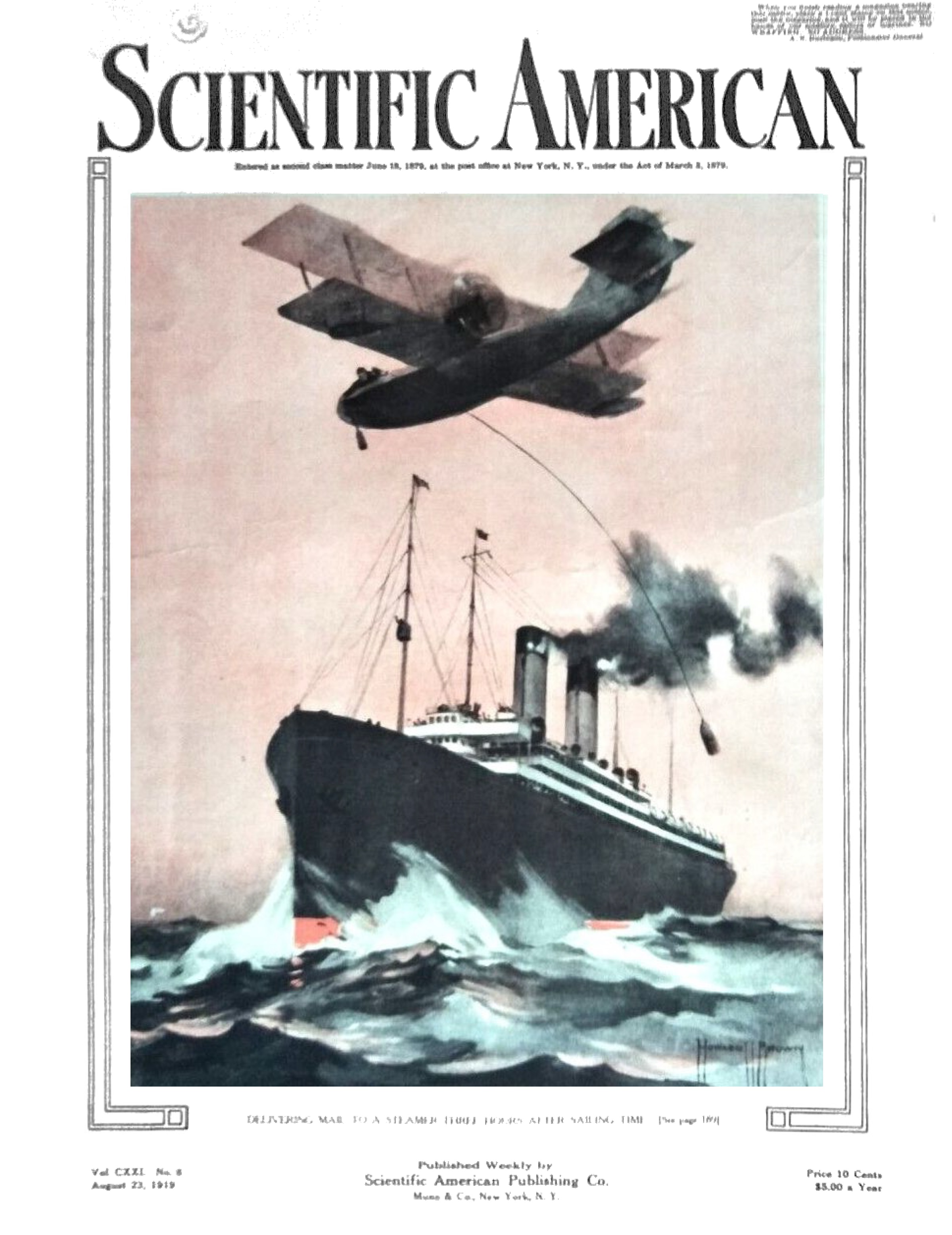

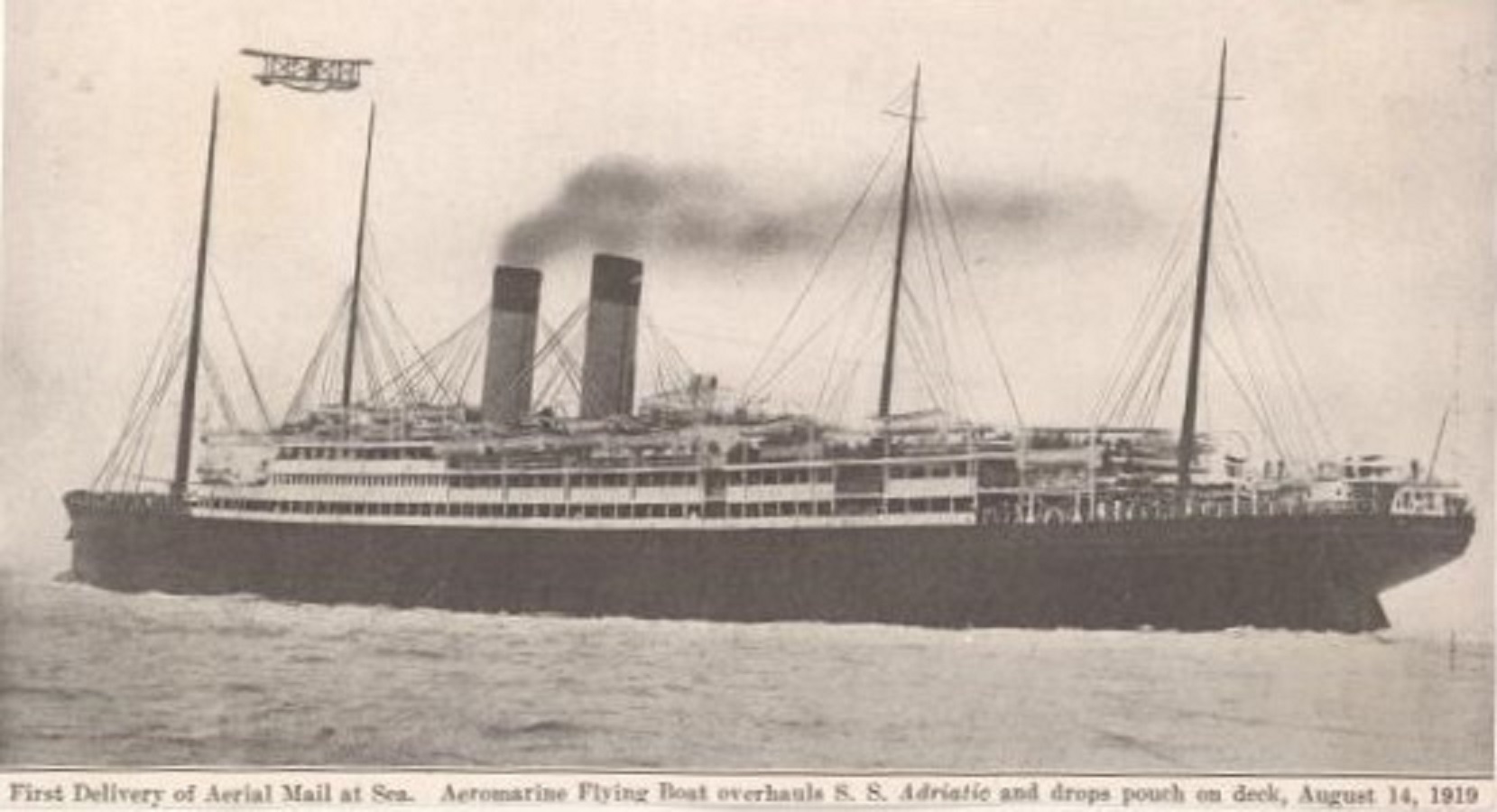

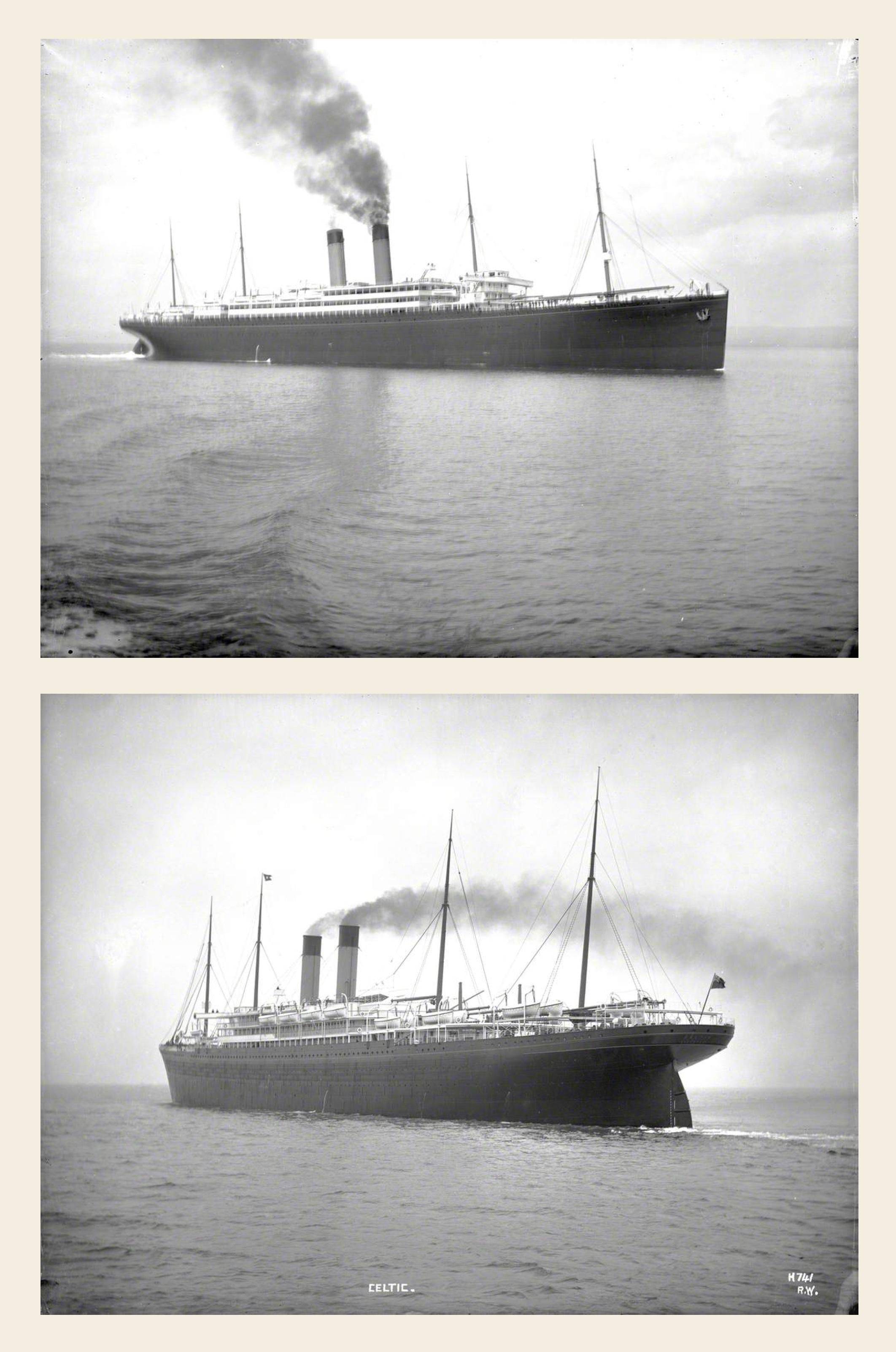

Fig. 1: White Star Line's ocean liner R.M.S. ADRIATIC - member of the famous "Big Four" - contributed to the first successful implementation of air-sea mail delivery. Depiction of the successful experiment carried out on August 14, 1919 on the front page of the "Scientific American" magazine (source).

Preface:

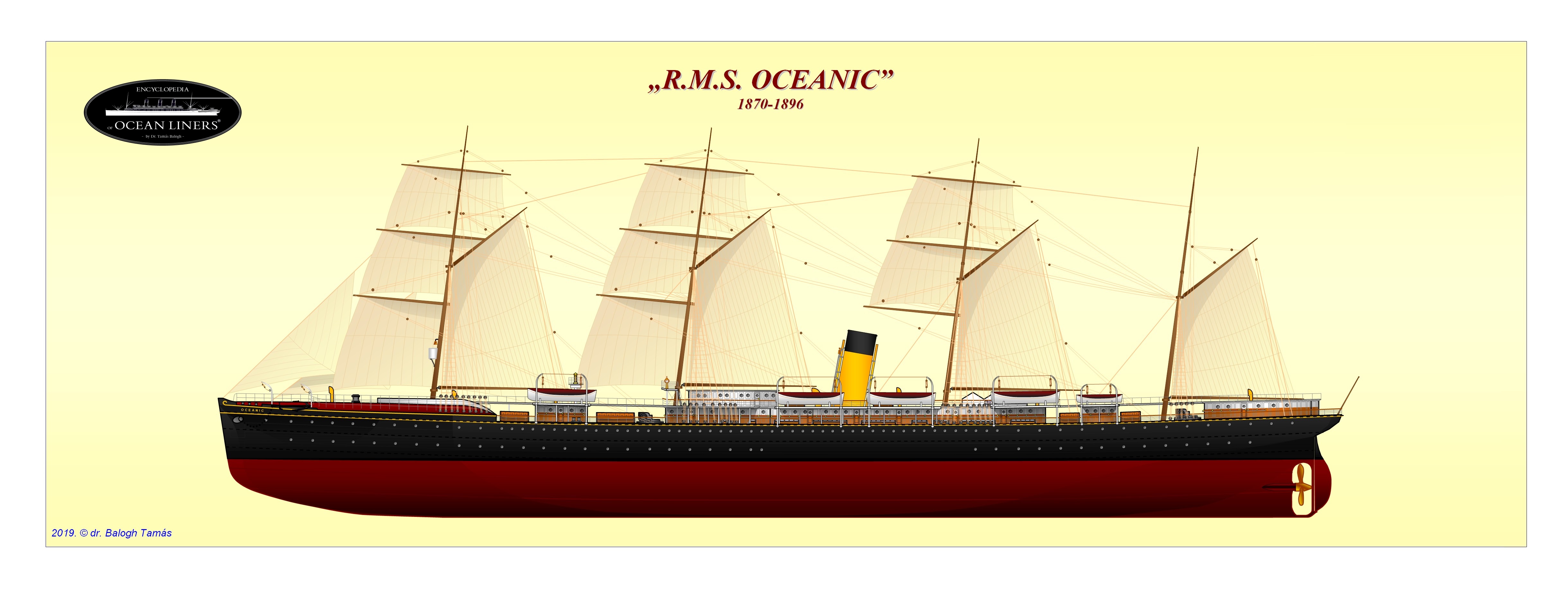

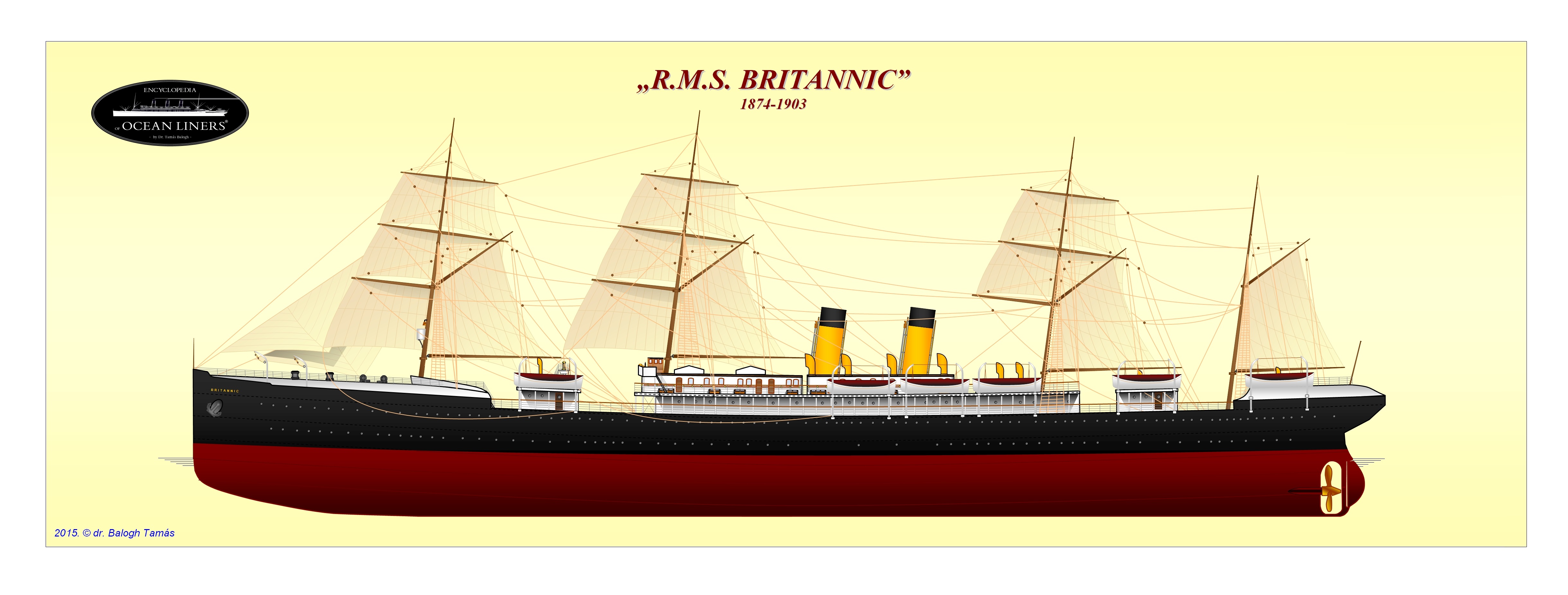

The American Wright brothers - small engine and bicycle mechanic Orville and Wilbur (both enthusiastic gliders, followers of the German Otto Lilienthal) - performed their first test flight on December 14, 1903, the 121st anniversary of Montgolfier's first hot air balloon flight and then three days later the first sustained flight with their heavier-than-air, guided aircraft, which they had been working on for years to develop. However, they managed to make the first full circle - 1.2 km long - only one year later, on December 20, 1904, with their perfected airplane. The American public was moderately enthusiastic about the invention, but the French Alero Club (which had been actively experimenting with the implementation of machine-powered aeronautics for some time) recognized the significance of the invention. In its own country, the airplane only gained more publicity in the context of the Hudson-Fulton Celebration held between September 25 and October 9, 1909, when a spectacular demonstration was organized for the various modes of transportation, and within this framework - as the latest achievement of steam navigation technology - the the British ocean liner LUSITANIA was also exhibited at the ceremony, which also included the public flight of Wilbur Wright, who gained world fame with his demonstration flights in Europe at the end of 1908 and the spring of 1909. As part of the celebrations, a demonstration flight from Governor's Island to the grave of General Ulysses S. Grant and back took place on September 29 and October 4. About one million New Yorkers were able to see the 33-minute flights and the LUSITANIA, although probably only a few of them suspected that they were witnessing the meeting of the past and the future, as fragile airplanes completely supplanted the celebrated mammoth ocean liners just 60 years later from transcontinental passenger transport. But until then, the two modes of transport existed side by side, and between the two world wars, their unique cooperation was also realized in the form of air-sea mail deliveries from land to ships and back.

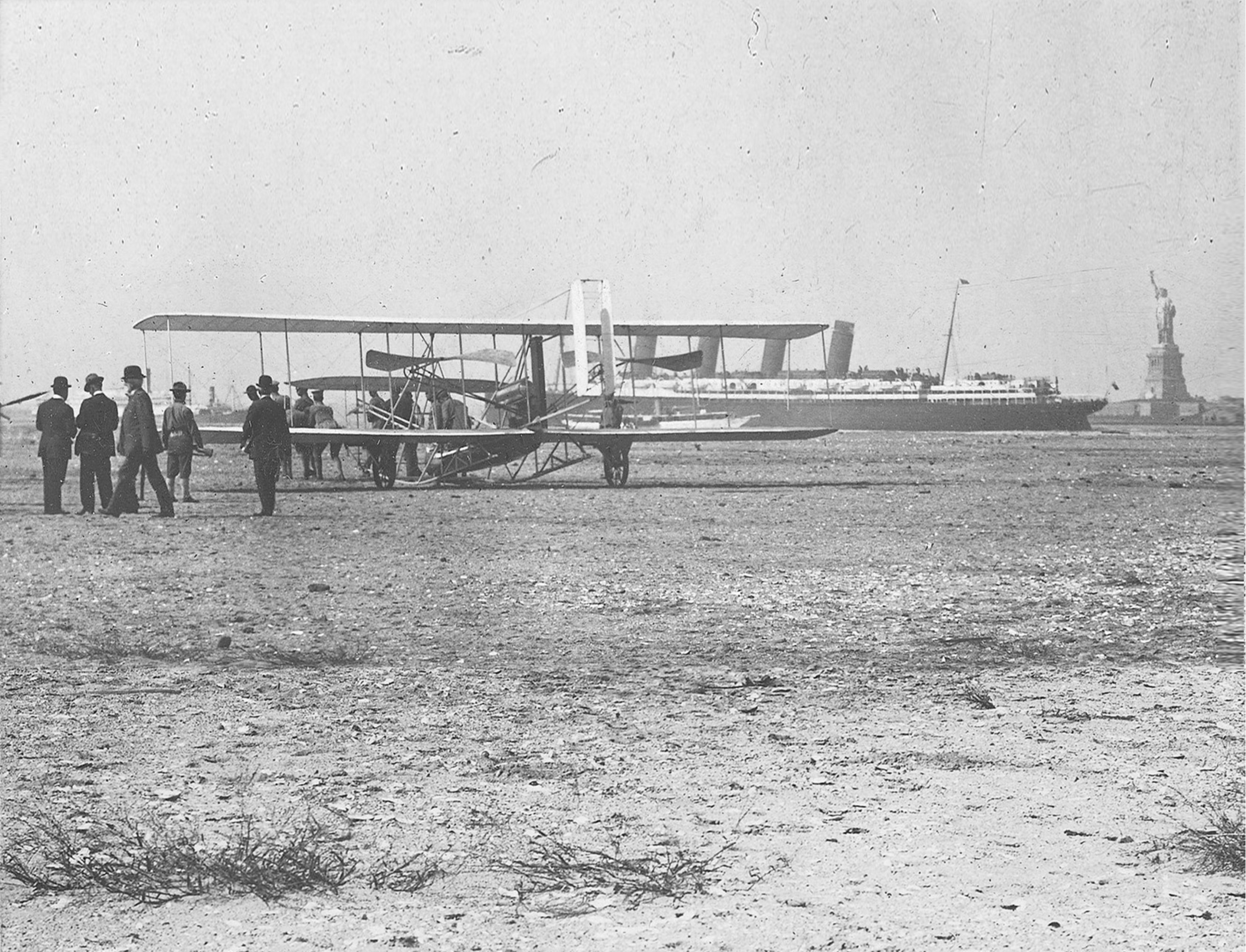

Fig. 2: Pilot Wilbur Wright and mechanic Charlie Taylor prepare to fly around the Statue of Liberty using the Wright "A" Flyer (the Wright brothers' fourth aircraft design) using Governor's Island Airport on September 29, 1909. In the background, the mighty LUSITANIA, speed record-holder of the oceans. (Source)

Introduction:

The beginnings of civil aviation can be traced back not only to the invention of aircraft before the First World War, but also to their develpoment during the war (i.e. for the spread of more and more reliable monoplanes, made of light metal - aluminum -, equipped with increasingly powerful engines, replacing older biplanes made of wood and canvas), and to the insatiable passion for flying of the trained pilots who survived the war. The experienced fighter pilots, who were left without a job due to the disarmament after the end of war, were happy to demonstrate their skills in public in order to earn money after their dismissal from the service, and at the same time indulge their passion. Many American pilots became members of various flying circuses (so-called "barnstorming"), which flew across the country in small and large cities, holding spectacular shows and entertaining paying passengers. The individual initiatives eventually turned into organized, group shows, and big airshows started all over the country, with air competitions, acrobatic stunts and imitation of aerial combat scenes (which also inspired Hollywood when filming movies about the First World War). In fact, the practice of today's Red Bull Air Race also has its roots in flying circuses. And one more thing: the continuous development. The aerial acrobats of the flying circuses also competed with each other for first place (who was more successful, faster, etc.), so their operation stimulated the development of controls, engines and airframes. The Schneider Prize, which was founded in 1913 and promised a reward of 1,000 pounds, and similar prizes led to a series of increasingly faster and slimmer monoplane designs: the pilots competing for the various prizes encouraged progress. One element of this was the expansion of civilian use of aircraft. Although transcontinental flight was the desired goal, it proved to be unattainable for a long time. On the other hand, the first, still isolated, attempts at airmail delivery took place before and during the First World War, namely in the United States.

Attempts to implement regular air and the first air-sea mail delivery:

1) The very first - unofficial - attempt was made before the invention of airplanes, on August 17, 1859, when John Wise tried to deliver 100 letters in his airship from Lafayette, Indiana, to New York. However, the attempt failed after a short flight of 60 km due to the lack of suitable wind, and after the forced landing, the mail was finally delivered by rail.

2) Had to wait for a good fifty years until the next attempt: A federal bill authorizing the US Postmaster General to investigate the practical applicability of airplanes in mail delivery was presented by Texas Representative Morris Sheppard on June 14, 1910. The proposal was not accepted, and the New York Telegraph mocked it like this: "Love letters will be carried in a rose-pink aeroplane, steered by Cupid’s wings and operated by perfumed gasoline. … [and] postmen will wear wired coat tails and on their feet will be wings."

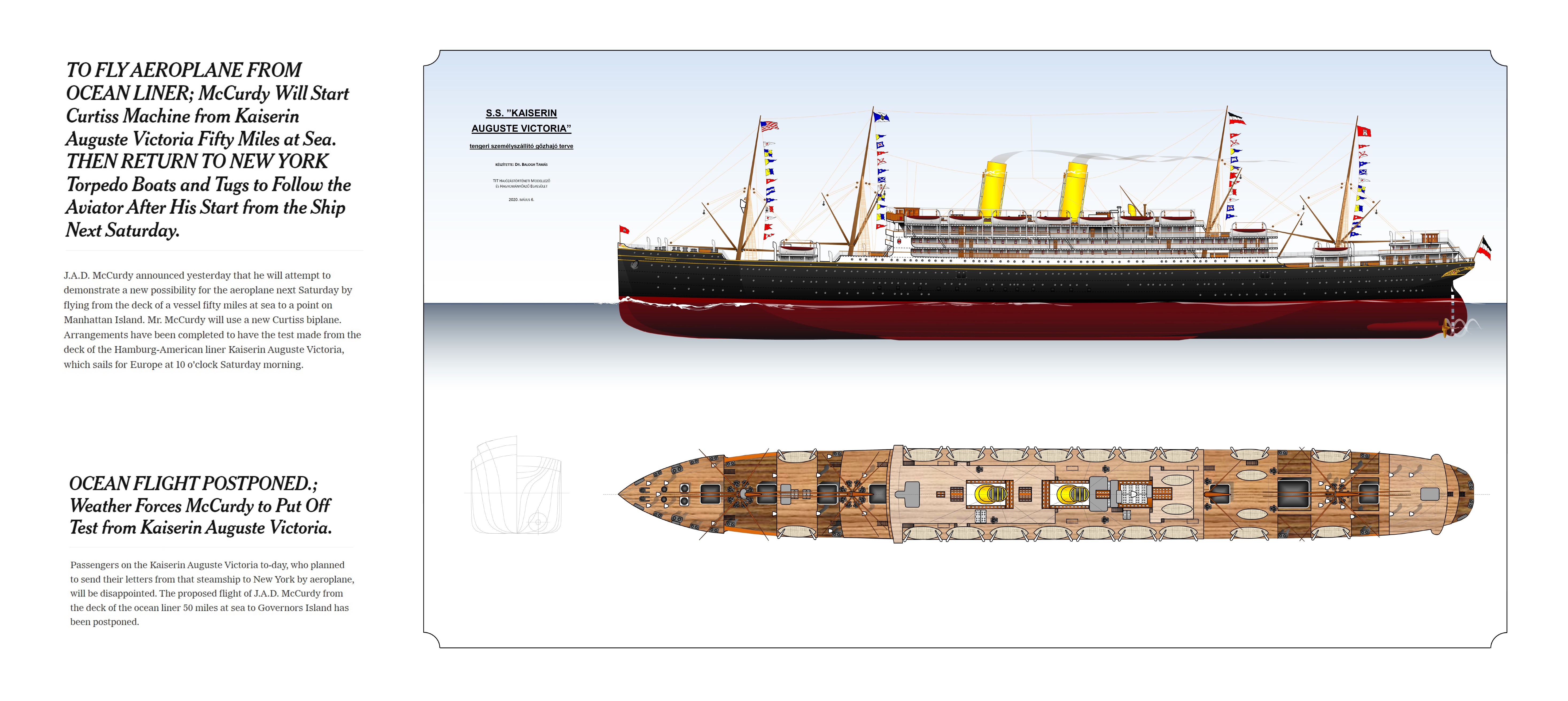

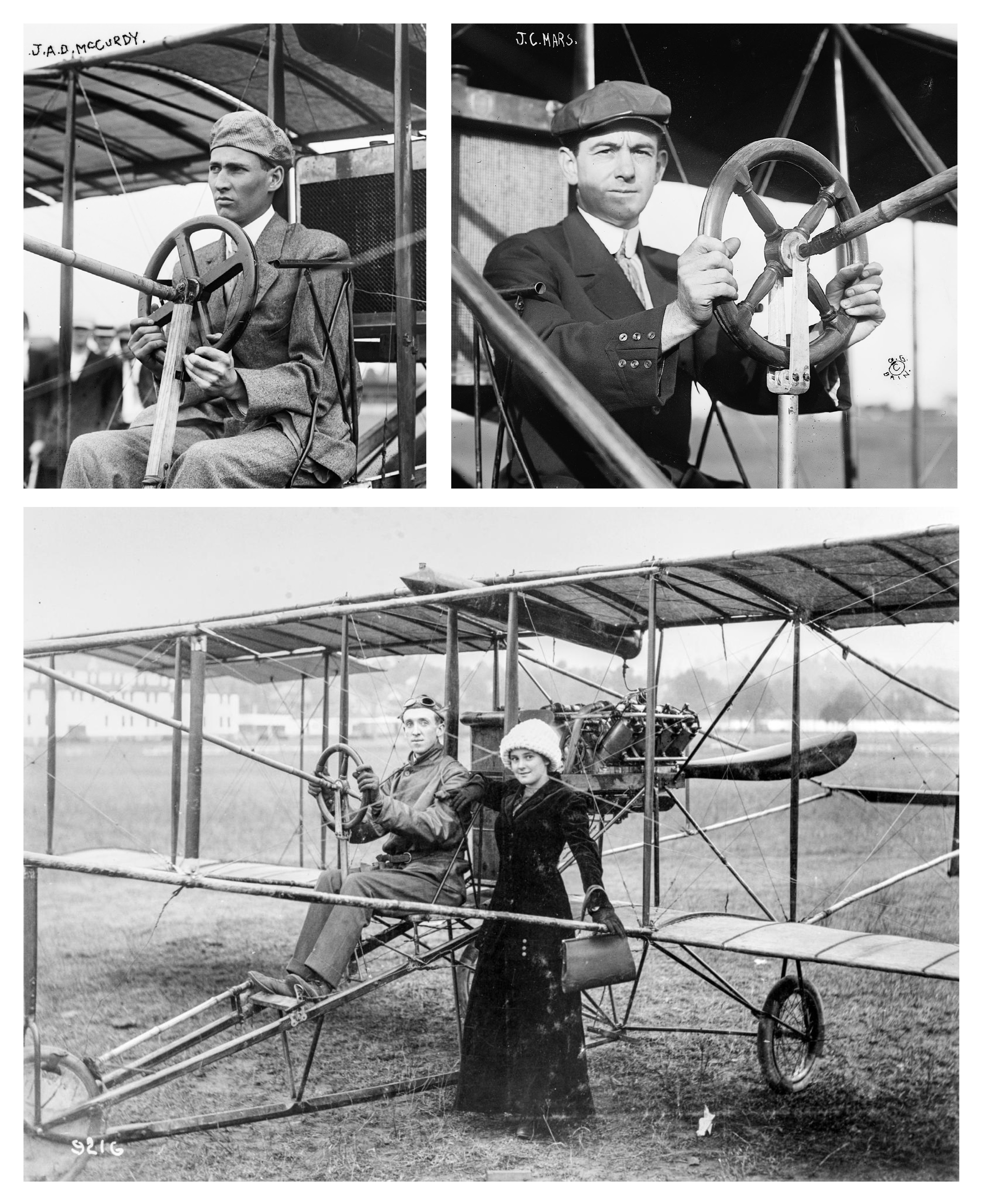

3) Despite this, Postmaster General Frank Hitchcock - a great fan of aviation - personally undertook to be a passenger in a Blériot monoplane at the air parade held in Baltimore on November 1, 1910. After the landing, he declared: "It will not be long before we are carrying the mails this way, that is certain", and on the same day he authorized the first official airmail delivery attempt, from aboard the German KAISERIN AUGUSTE VICTORIA, an ocean liner traveling on the high seas from America to Europe. Based on an agreement between an American daily newspaper "New York World" and the Hamburg-America Line shipping company, the Canadian John Alexander Douglas McCurdy (son of Alexander Graham Bell's secretary) had to lift an American-made Curtiss airplane into the air, from a 100-foot (30.5 m) long platform, installed on the bow of the ship navigating in 50 miles (92.5 km) distance from the shore. The platform was built on the bow of the ship, because the speed of the ship and the plane going in the same direction were added together, which shortened the take-off distance and increased the chance of a successful take-off. However, the attempt scheduled for November 5 was canceled due to bad weather (a fierce north-easterly gale damaged all the aircraft in the air parade, including McCurdy's, so he could not carry out the task), even though - if successful - this would have been the first case in history for an aircraft to take off from a ship's deck.

Fig. 3: Contemporary newspaper articles in The New York Times about the KAISERIN AUGUSTE VICTORIA and the experimental flight to be carried out on her board (source: here and here, drawing: Dr. Tamás Balogh © 2020).

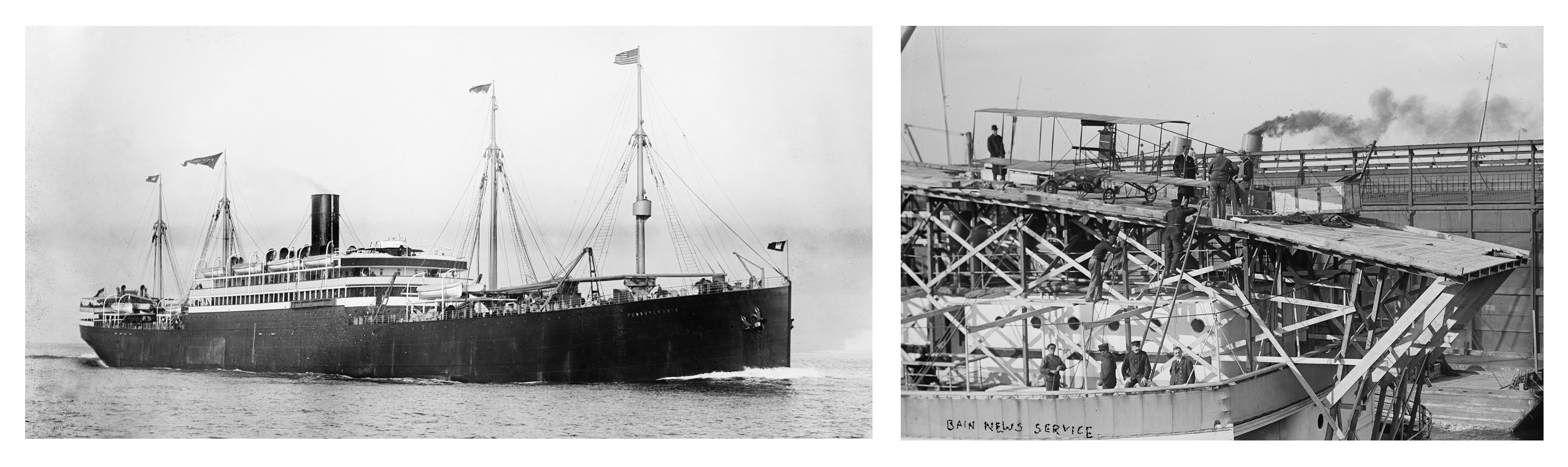

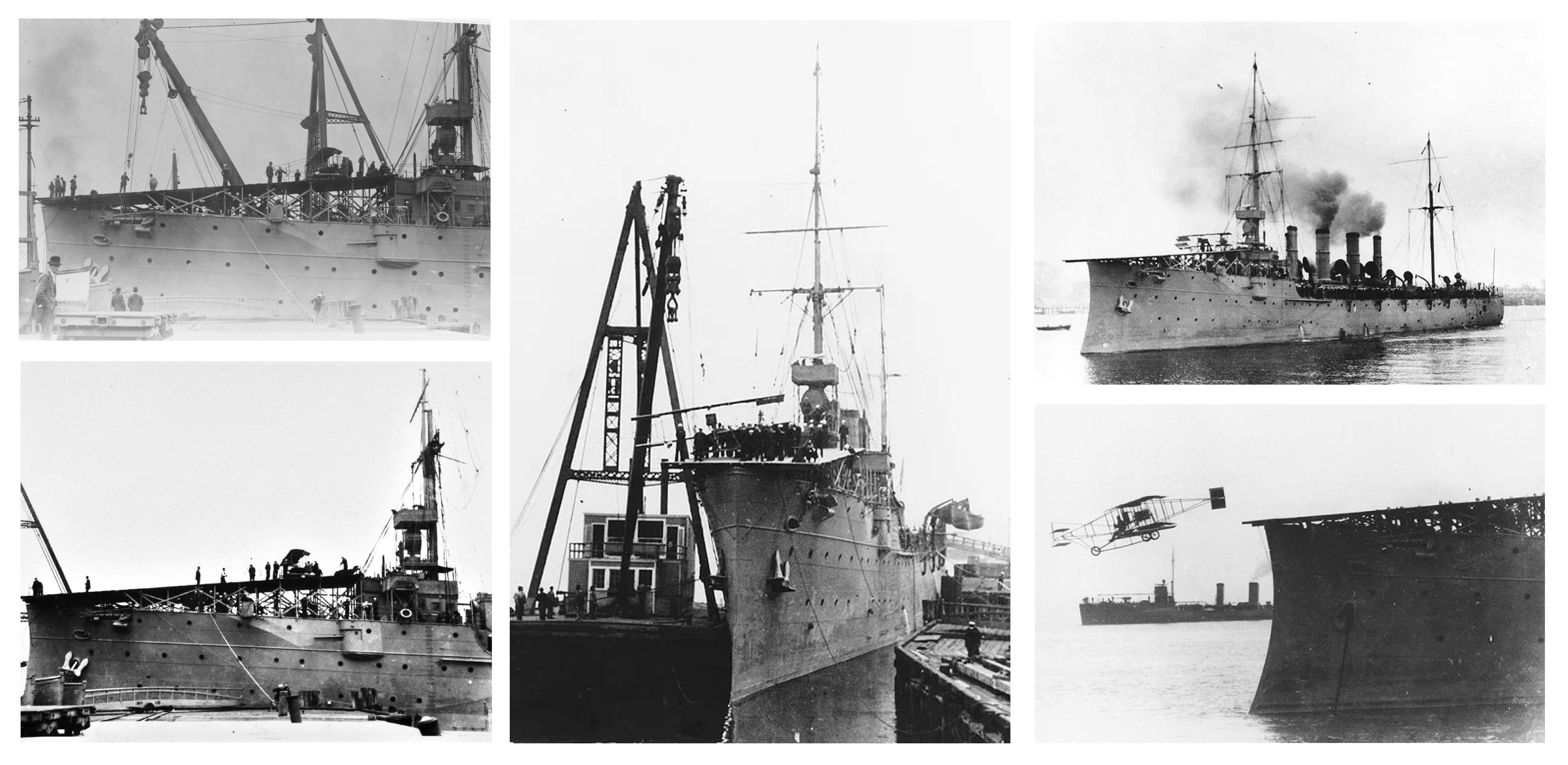

4) Since the experiment also had a hidden military aspect - the Curtiss company, which provided the aircraft for the experiment, hoped to get a naval order due tot the demonstration of its efficiency: "an aircraft can be launched from the deck of a ship while the ship is in motion." – Curtiss had no intention of giving up the priority, so on November 7 it was announced that the attempt would be repeated 5 days later on board another German ocean liner, PENNSYLVANIA, which was about to set sail. However, this ship was not only significantly smaller and slower than KAISERIN AUGUSTE VICTORIA, but her design only allowed for an 85-foot (26 m) long launch platform to be built on the top of her stern superstructure instead of the ship's bow. This meant that the ship's engines, 8 miles (15 km) east of Fire Island, had to be put into reverse to allow McCurdy to take off safely in a 10-knot (18.5 km/h) headwind. The plane then had to follow a 50-mile (92.6 km) route along the coast of Long Island to Governors Island, New York, where it could collect a $500 prize offered by businessman John Barry Ryan. The tension was heightened by the fact that, on November 9, the US Navy also prepared for the first successful shipboard aircraft launch, when, at the suggestion of the other faction of the Curtiss company in direct negotiations with the Navy, preparations were made for the construction of a launch platform on board the cruiser USS BIRMINGHAM (At the initiative of Admiral George Dewey, who became famous in the Battle of Manila in 1898, the Navy purchased its first aircraft in June 1909, and from October 1909 it actively investigated the possibility of involving aircraft in the execution of the reconnaissance tasks of the fleet, for the first time in a period when the whole world was still 50 aircraft were in military service, but no one had ever managed to take off from a ship). On November 11 – one day before the scheduled date of the experiment – McCurdy crashed at an air show and, although not seriously injured, was unable to reach the Hoboken pier of the Hamburg-America Line in time, so Curtiss sent the 34-year-old James Cairn Mars, instead of McCurdy.

Fig. 4: The steamer PENNSYLVANIA and the launc platform installeed on her stern superstructure in Hoboken. Source: here and here.

On November 11, one day before the test was scheduled to take place, McCurdy crashed at an air show, and although he was not seriously injured, he was unable to make it to the Hoboken pier of the Hamburg-America Line in time. So the 34-year-old James Cairn Mars co-pilot was alerted, who made a name for himself with his parachute jumps and as a pioneer pilot (he was the owner of the eleventh flying licence in the USA). The weather conditions turned out to be ideal this time, but a rubber tube – forgotten on the lower right wing of the plane – crashed into one of the wooden propeller wings in the vortex created after the propeller was started and broke off two smaller pieces, which flew out with great force and injured a sailor standing nearby, and they broke the steel wire leading to the aileron of the aircraft, making the plane uncontrollable and failing to take off. This is how it happened that the world's first successful shipboard aircraft launch finally took place 2 days later, when Eugene Burton Ely took off from the deck of the cruiser USS BIRMINGHAM, and then - in another attempt - made the first successful landing on the deck of the cruiser USS PENNSYLVANIA , on January 28, 1911, from which he took off again a few hours later that day.

Fig. 5: Pilots who were selected to be the first: J.A.D. McCurdy (1886-1961), J.C. Mars (1875-1944) and E.B. Ely (1886-1911), here were photographed together with his wife Mabel (source: here, here and here).

Fig. 6: Preparation of the cruiser USS BIRMINGHAM for the test, and E.B. Ely's first take-off from a ship (source: here, here, here, here and here).

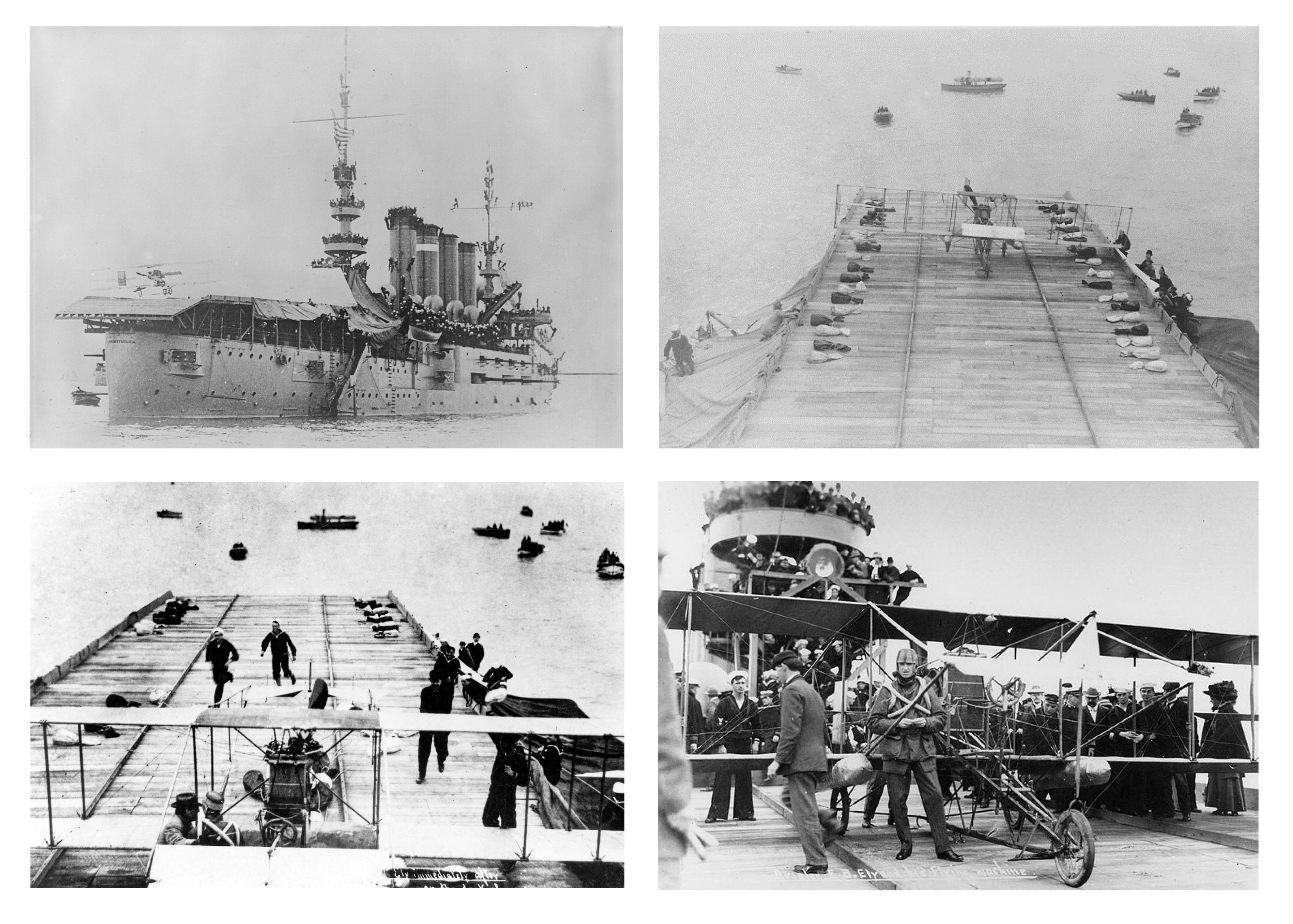

Fig. 7: USS PENNSYLVANIA and E.B. Ely's first shipboard landing (source: here, here, here and here). As an interesting fact, in the second and third pictures you can see the sandbags placed opposite each other on the edge of the platform, which - more precisely, the ropes stretched between them - braked the landing plane. This type of cable brake system (together with the steam catapult shown in Fig. 9) is still a basic element of the operation of modern aircraft carriers.

5) However, Postmaster General Hitchcock remained resolute. Pilot Earle Ovington was thus able to deliver the first airmail he had officially sent over a year later, on September 23, 1911 - but only on land instead of sea. Over the next few years, dozens of test flights were authorized at fairs, carnivals and air shows in more than 20 states. These flights convinced officials that airplanes could indeed carry mail. Beginning in 1912, therefore, postal officials petitioned Congress for the appropriation of funds to start an airmail service, which finally authorized the use of $50,000 in 1916 for this purpose. The government then issued requests for bids to contract providers in Massachusetts and Alaska, but received no acceptable responses. In 1917, the budget to establish an experimental airmail service was increased to $100,000 for the following fiscal year. So finally, in February 1918, the US Post Office issued a call for proposals for the purchase of airplanes, but the call was withdrawn a few weeks later, as the air mail service wanted to be operated by the Army Signal Corps in order to increase the number of flight hours and to improve training of its pilots. The scheduled air mail service finally started following the agreement of the postmaster general and the secretary of war on May 15, 1918, with planes and their pilots lent by the army.

Fig. 8: Postmaster General Frank Hitchcock hands pilot Earle Ovington the first official United States airmail shipment (top left), delivered by the pilot in his Blériot monoplane (top right). The first scheduled airmail shipment leaves Philadelphia (below left) and is picked up by local postmaster Thomas G. Patten from Lt. Tory Webb in New York (below right). Source: for all images here.

The idea arise again:

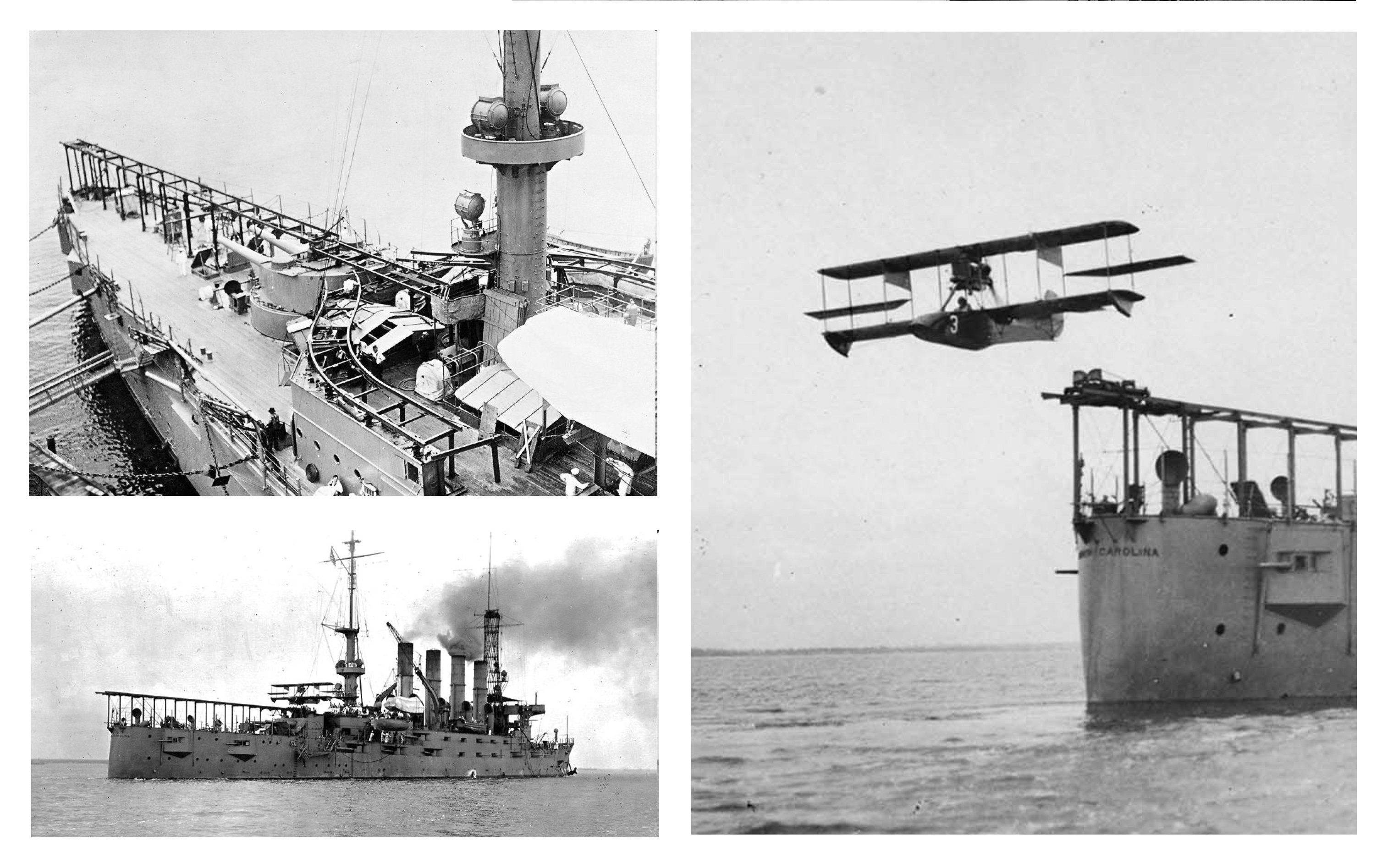

Airmail delivery started and became regular on the continent, but the problem of airmail delivery from shore to ships on the high seas, and from ships to shore, remained unsolved. In the First World War, warplanes serving with the navies, but without on-board radios, were sometimes forced to drop important message to their own warships in battle, but this solution was considered more of a feat and a particularly lucky coincidence than a reliable technical solution. (In the naval battle at the Otranto Strait on May 15, 1917, for example, the Austro-Hungarian naval flying boat K-195 (piloted by Emmanuel Lerch and Béla Lenti) dropped a report in a tin box on the position of the cruiser NOVARA, damaged in the battle, barely from the altitude of 5 m onto board the armored cruiser SANKT GEORG, the lead ship of the relief forces, rushing to the scene of the battle with full steam. Thanks to the courage and knowledge of the pilots, the report reached its destination despite the strong wind blowing at the site.) The development and implementation of such a solution was made difficult by the fact that, although the very first airplane takeoff from a ship's deck took place in 1910, no one had yet taken off from a moving ship (the USS BIRMINGHAM was at anchor at the time of E.B. Ely's experiment). Nevertheless, the new world record did not have to wait long. Although the first Curtiss experiments which were planned with the involvement of German ocean liners already wanted to carry out the task of taking off from ships that were in motion, during the war, for understandable reasons, the Germans could not really be persuaded to do such a thing. The United States, on the other hand, did not have ocean liners large enough to continue the experiments independently. Thus, the cruiser USS NORTH CAROLINA became the first ship in history to launch an airplane while underway, using its onboard steam catapult, in Pensacola, Florida on November 5, 1915. Designed by Glenn Curtiss of San Diego, AB2 was piloted by Corvette Captain Henry C. Mustin. (Eugene B. Ely's takeoffs on November 14, 1910 and January 8, 1911 did take place from a ship deck launch platform, but his takeoff was not assisted by a catapult). The experiments carried out on the cruiser proved that with the help of platforms of suitable size installed on board ships, not only the launch of aircraft on the ship deck, but also their landing - thus the transport of passengers and/or goods (mail) by air and sea - can be ensured.

Fig. 9: Take-off assisted by a steam catapult from the deck of the USS NORTH CAROLINA. Although the airplane is an American invention, the domestic public was initially uninterested in it, and the Wright brothers were distracted from further development by the multitude of patent lawsuits. As a result, America entered the First World War without having its own planes that could be used reliably, it had to buy French planes, and they tried to make up for the backlog with military-initiated developments (source: here, here and here).

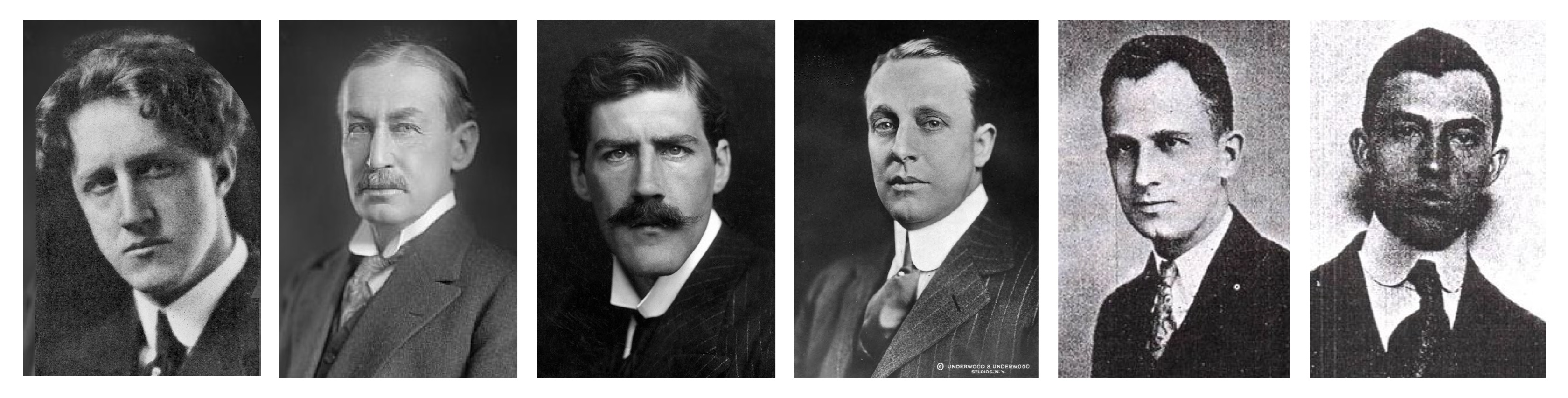

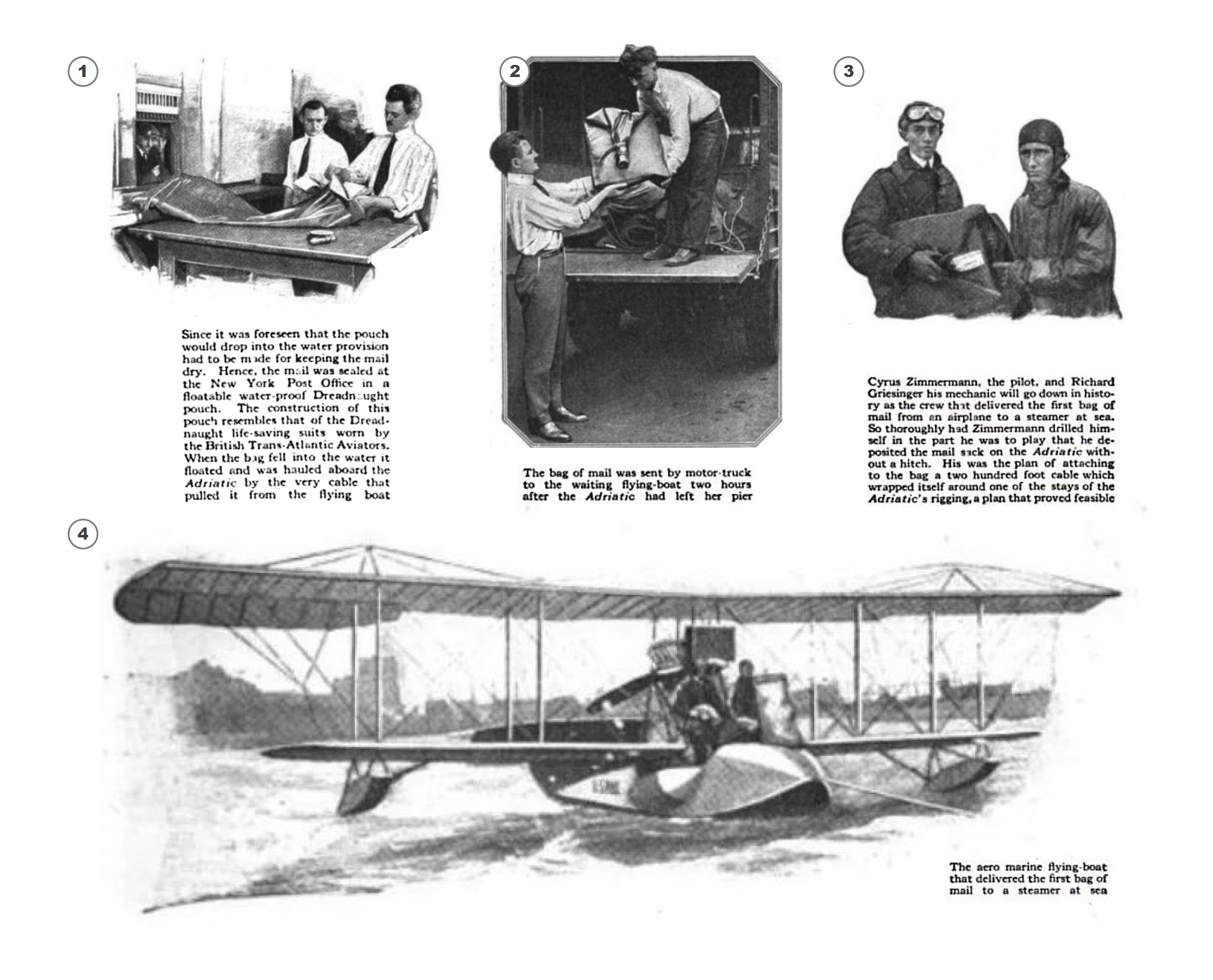

The idea came from Waldemar Kaempffert, the editor-in-chief of Popular Science Monthly, the American science popularization magazine of the time, who turned to Postmaster General Albert Sidney Burleson, who had been in office since 1913. The postmaster supported the initiative and ordered his second deputy, Otto Praeger, to carry out the necessary organizational tasks. Praeger entered into a relationship with New York postmaster Thomas G. Patten, who proved to be an ideal partner for the attempt: he won the support of David Lindsay, executive of the International Mercantile Marine Co. (IMMC) - the American-owned group that owns the White Star Line shipping company registered under British law - and Governor of the Maritime Transport Associationby. In the meantime, Kaempffert made an agreement with the famed American businessman of the time, Inglis Moore Uppercu, an investor in aircraft, car and motorcycle production, who founded the first regular passenger transport airline in 1919, Aeromarine Airways, and recognized the excellent advertising opportunity. The task of implementing the idea was given to Paul Gerhard Zimmermann (1890-1962), chief engineer of the Aeromarine company, and his brother, pilot Cyrus Johnston Zimmermann (1892-?), took the main role in the implementation. They both started in the automotive industry, and during the First World War they started working in aviation. In 1917 they were employed by the Curtiss Airplane and Motor Co., Buffalo, and in 1918 joined the Aeromarine Plane and Motor Co., where Paul became chief engineer and Cyrus became chief test pilot.

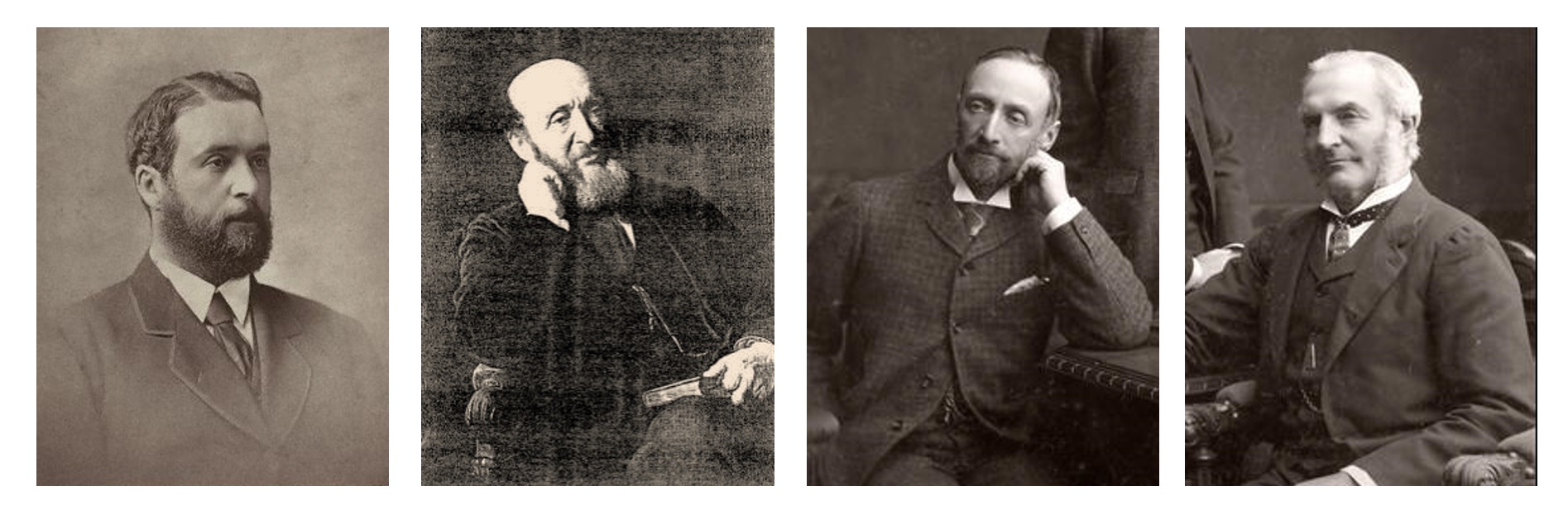

Fig. 10: The key figures of the experiment: Waldemar Kämpffert, editor-in-chief of Popular Science Monthly; Thomas G. Patten, Congressman, Postmaster of New York; David Lindsay, 27th Earl of Crawford, British Secretary of State for Transport 1916-1920; Inglis Moore Uppercu, Owner-CEO of Aeromarine; Chief designer Paul Gerhard Zimmermann and test pilot Cyrus Johnston Zimmermann (source: here, here, here, here, here and here).

The big experiment:

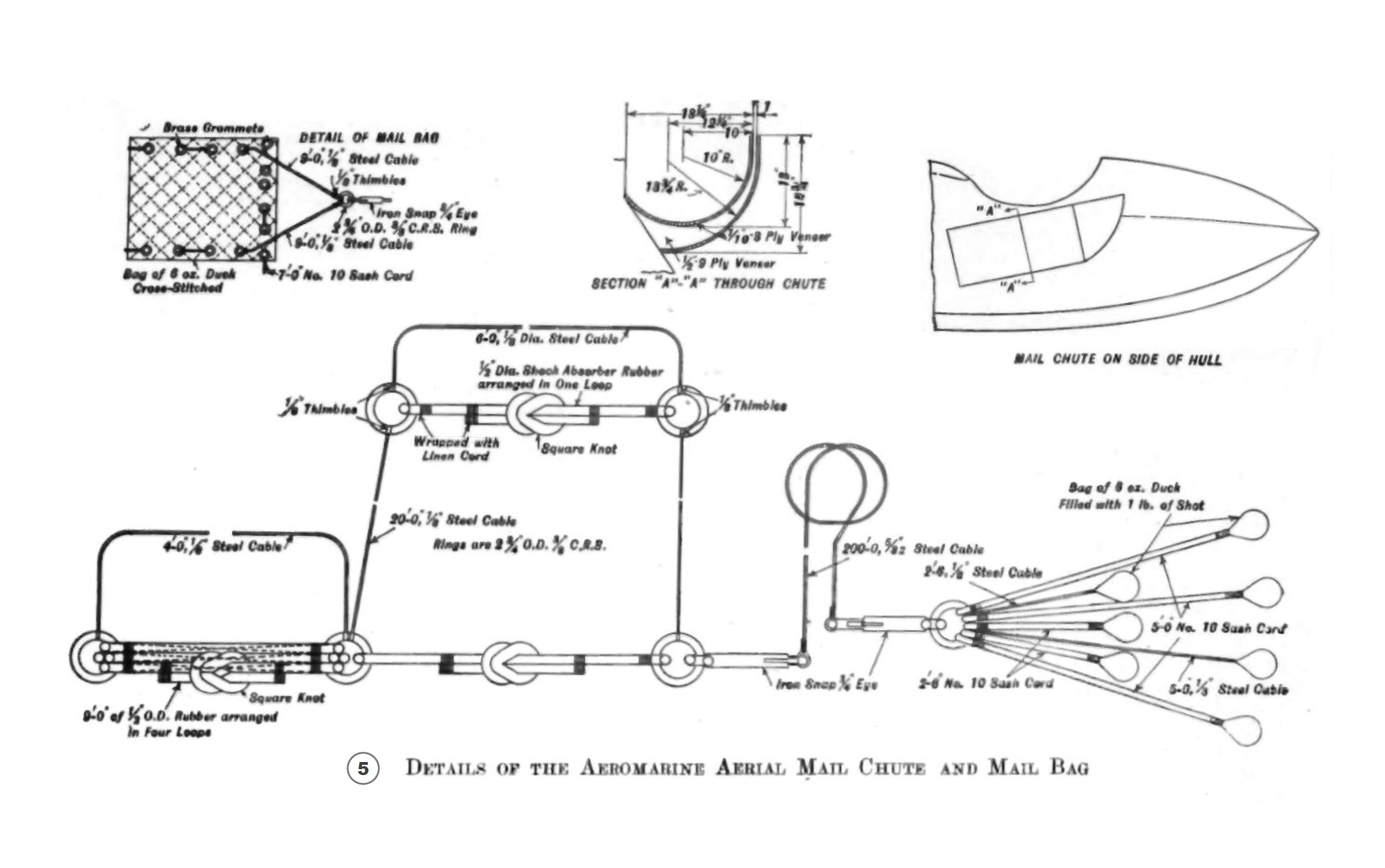

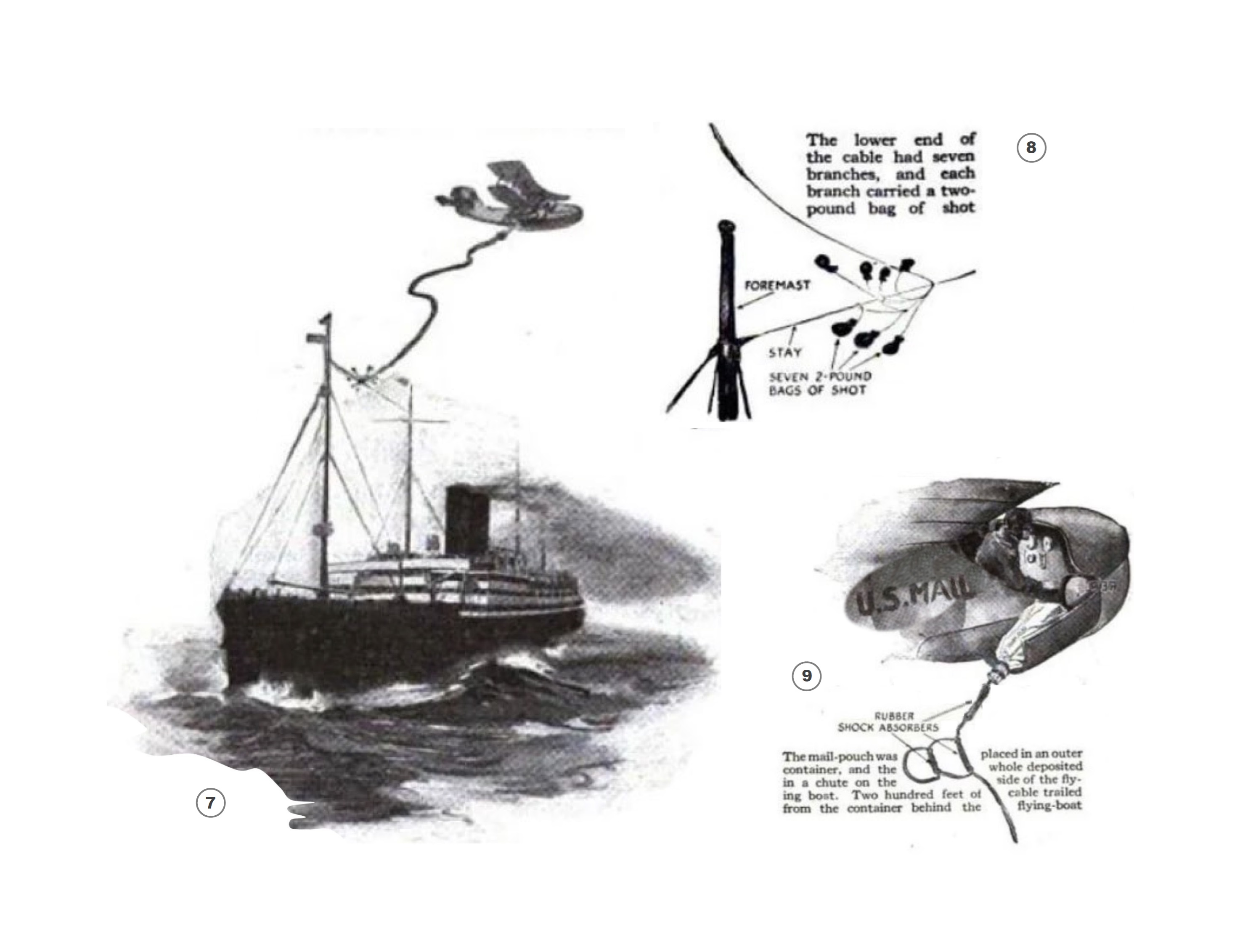

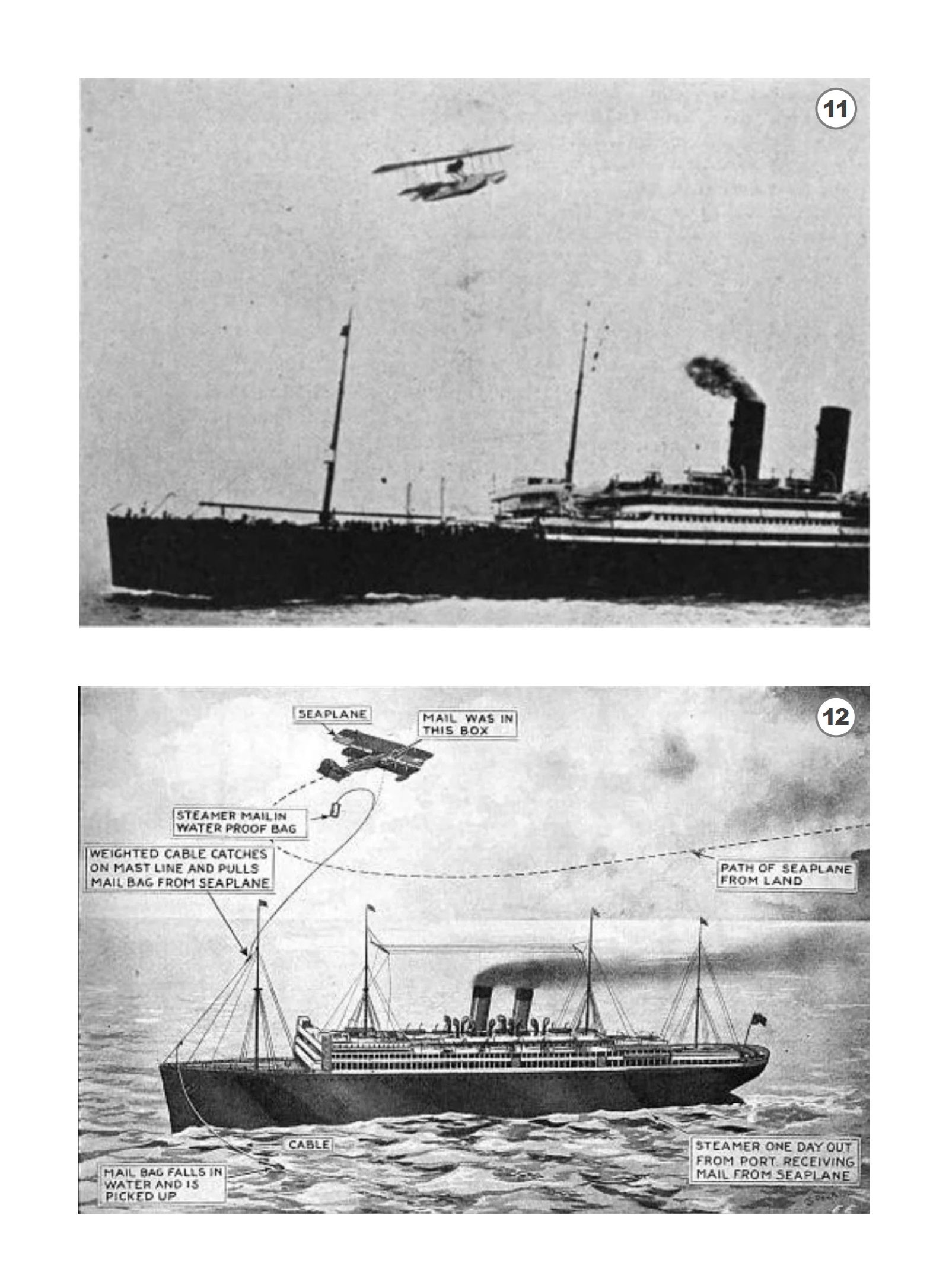

To prepare the experiment, the stakeholders formed committee to determine the details of the implementation. IMMC undertook to involve White Star Line's steamer ADRIATIC (which was arriving in New York on her first civilian voyage after World War I) in the experiment, while the Aeromarine company offered one of its newest flying boats (8.8 m long, 14.8 m span, biplane model 40C equipped with a 100 HP Curtiss engine, which could fly 403 km at a speed of 114 km/h). The organizing committee finally decided on an action to be carried out with the cooperation of the ship and the aircraft. The essence of this was that the aircraft crew should not simply drop the mail bag onto the ship (since the almost 50 kilo mail bag could have caused serious personal injury if it fell onto a deck crowded with passengers), but attach it to a cable, and only connect the cable on the ship, and let the bag at the other end of the cable fall into the water near the ship, from where the ADRIATIC's crew will be able to take him on board easily by the cable attached to the ship. For the idea to work, it was necessary to design the cable in such a way that it could be attached to the ship, the mail bag had to be waterproof, and perfect timing also required from the pilots.

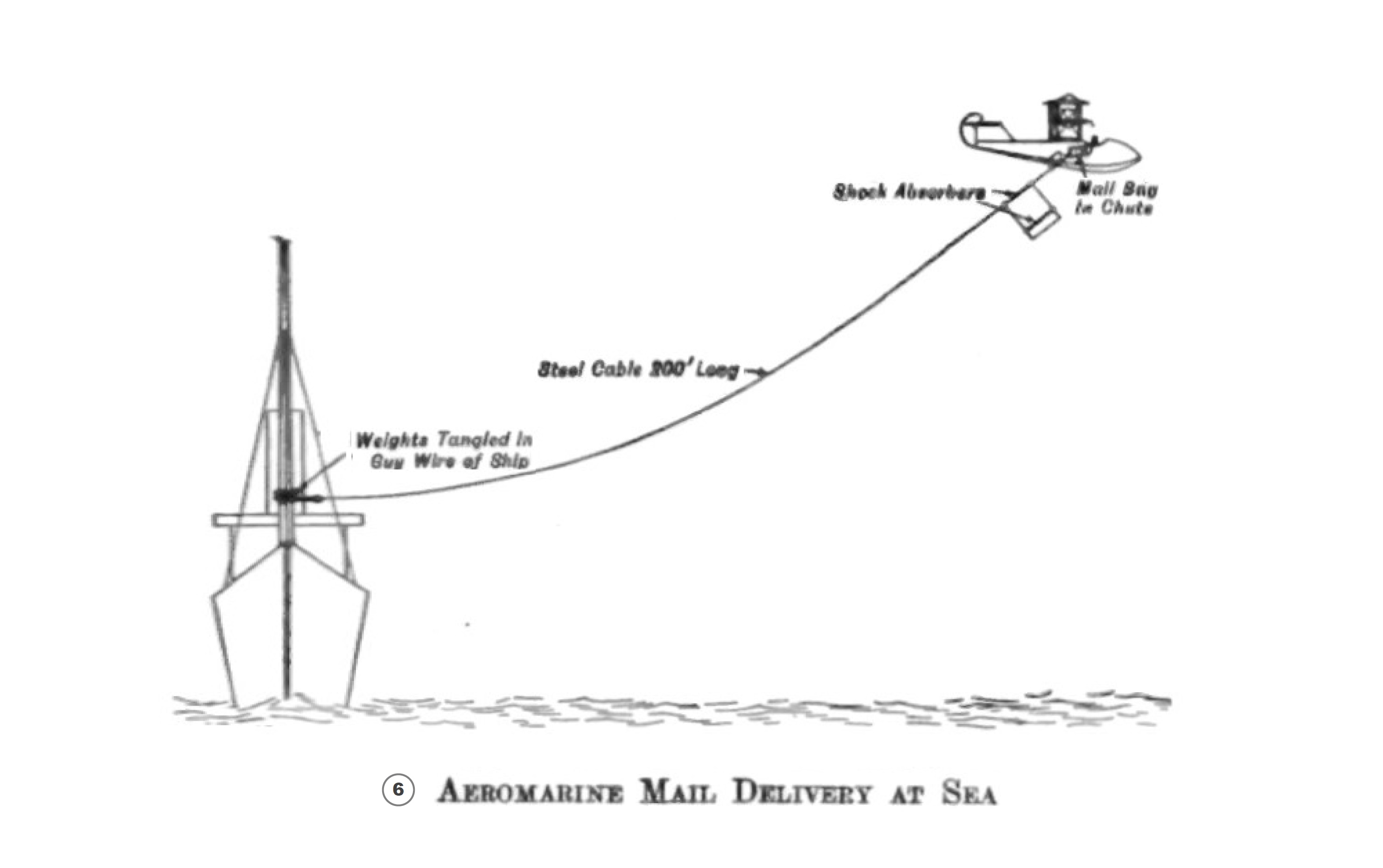

The proper design of the cable was ensured with two solutions: On the one hand, the free end of the cable was designed as divided into seven branches, and shot-filled 1 kg bags was attached to each branch as a counterweight. On the other hand, a strong rubber shock absorber was mounted on the other end of the cable attached to the mail bag. The idea was for the aircraft to fly across over the ship, while hangs the 60 m long cable down and tows it behind itself at a low altitude. As soon as the cable hits the rigging of the ADRIATIC, the seven branches of the free cable end with the attached counterweights, obeying the force effect resulting from the sudden stop - in the direction opposite to the plane's direction of travel - are wrapped around the ship's rigging, in this way creating the necessary connection between the ship and the mail bag attached to the other end of the cable on an airplane. As the plane flies further and further away from the ship, the cable entangled in the rigging tightens, and finally pulls the mail bag placed there from the chute-like container on the side of the plane, which falls under its own weight into the water next to the ship, from where the cable entangled in the rigging can be picked up by the ADRIATIC's crew. The shock absorber at the other end of the cable attached to the mail bag was used to prevent the breaking off the towed cable from the mail bag, during the suddenly stop when it hits the ship's rigging (or at the accompanying fast and strong jerk). For this purpose the shock absorber was made of solid rubber like the wheels of airplanes. This solution alowed the slight stretching of the cable without having to worry about breaking it off.

The integrity of the postal items was ensured by a waterproof pouch made of vulcanized rubber that could be closed with a buckle and a padlock, in which the mail bag was packed. The cable used for the delivery was attached to this pouch. The pouch was made in such a way that the thicker and heavier layer of rubber placed on the bottom served as a float to keep the pouch in a vertical position while floating in the water. In the floating position, two-thirds of the pouch was submerged and only one-third rose above the water level. Around 400 letters could be placed in the mail bag.

The functionality of the plan depended on the pilot, who had to descend so low with his plane that the 60-meter-long cable being towed behind it could come into contact with the rigging of the ADRIATIC. In other words, the pilot had to get dangerously close to the ocean liner without crashing his plane.

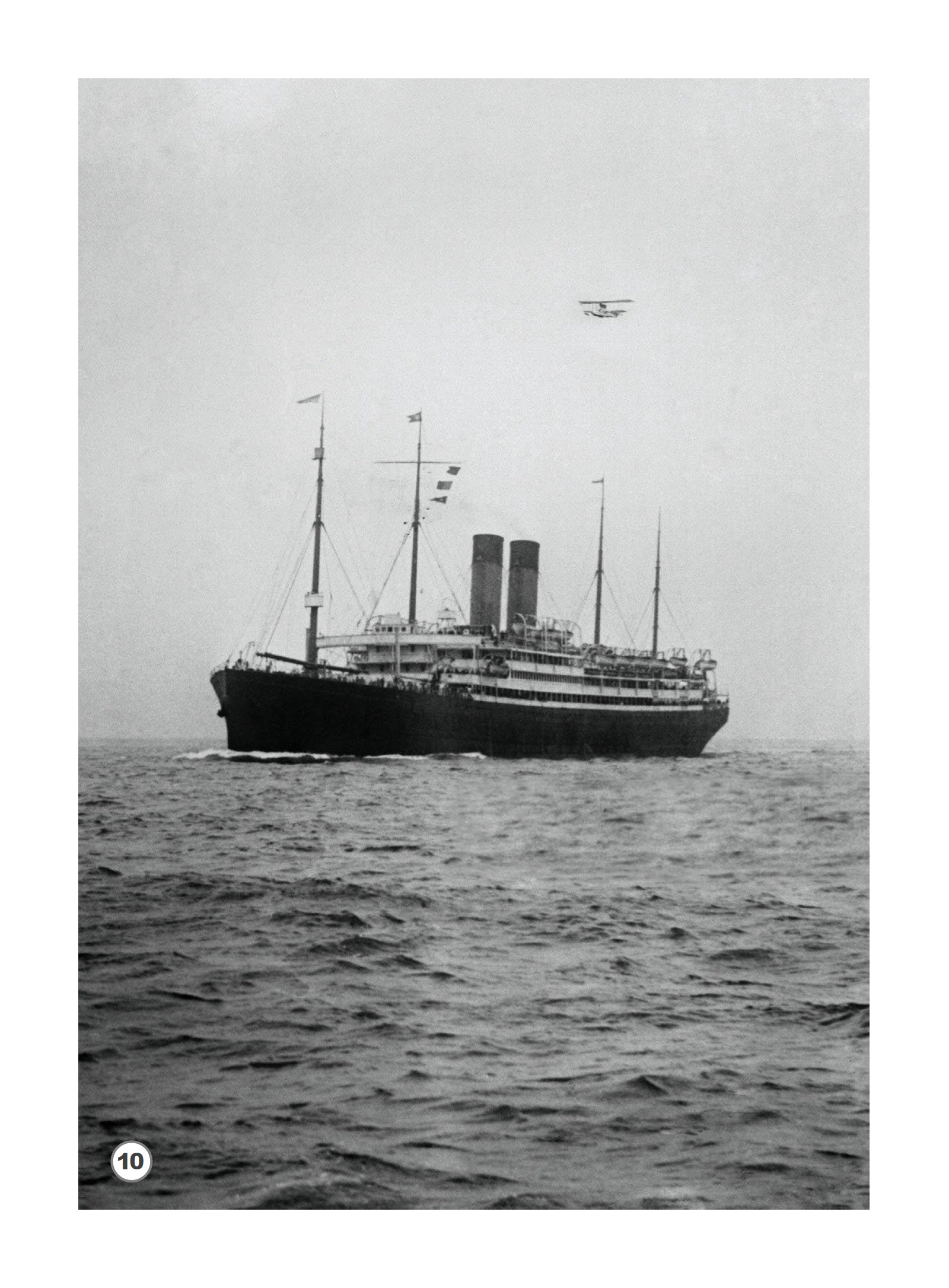

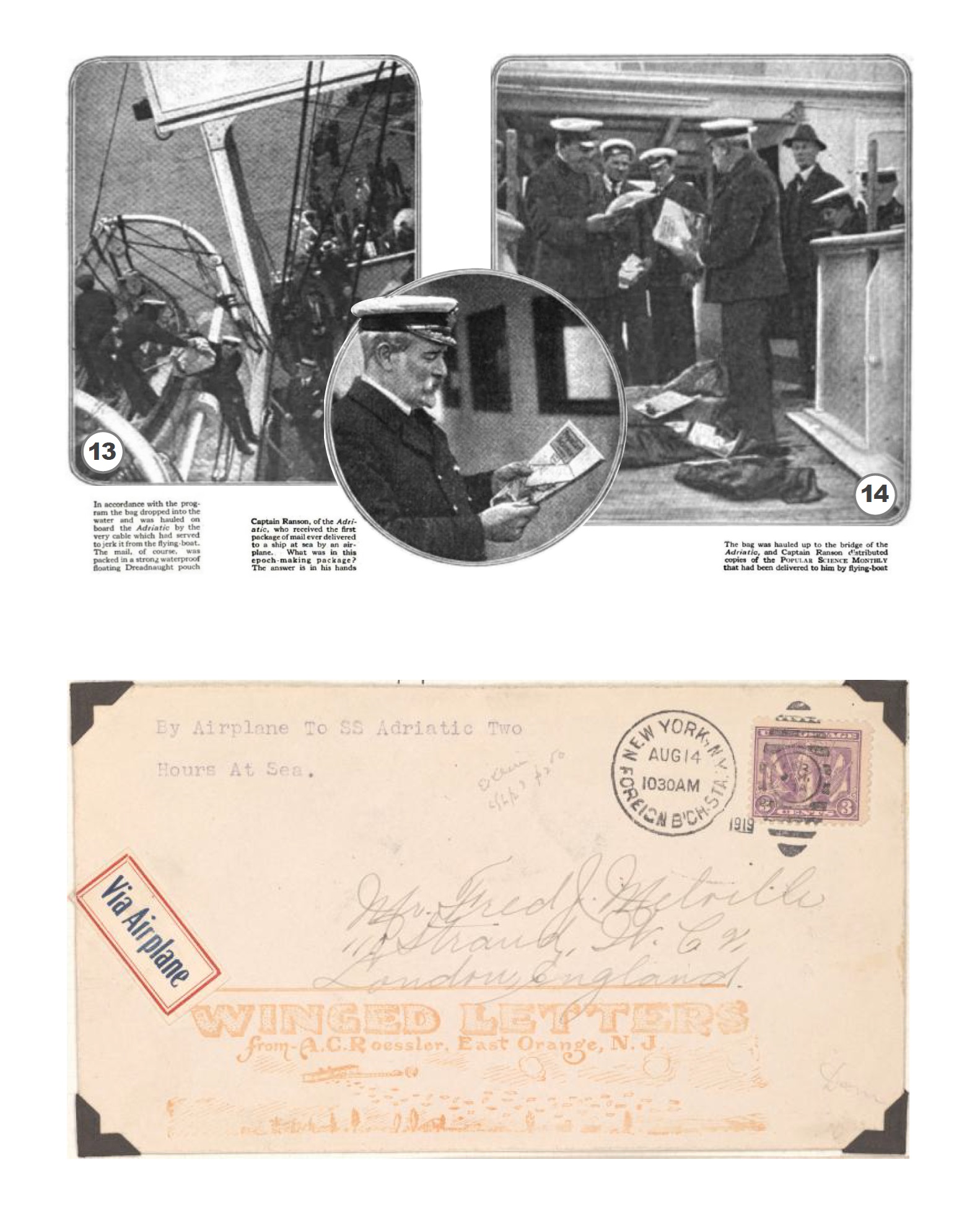

The experiment was carried out on August 14, 1919. ADRIATIC left New York half an hour late after the announced departure time of 12:00 noon. The Aeromarine 40C took off almost two hours after the steamer's departure, in strong gale, but overtook the ADRIATIC just as it was passing out of the Ambrose Channel. The plane made two circles above the liner, then decreased its altitude and when it approached the ocean liner to within 30 meters, pilot Zimmermann released the cable, which, during the flight across over the ship, wound itself on the ship's rigging as planned, pulling the mail bag packed in a waterproof pouch out from the chute attached to the side of the aircraft. The mail bag fell into the water next to the ADRIATIC, from where the ship's sailors fished it out and brought it to the bridge in front of the captain.

Fig. 11: Illustrations of the contemporary press (source: here).

Fig. 12: Devices designed for air-sea mail delivery: the waterproof pouch, the chute attached to the side of the airplane and the weighted branch rope (source: here)

Fig. 13: Illustration of the experiment: 6) A branch rope with a counterweight at the lower end is wrapped around the rigging of the ship, the force of the pulling of the 60 m long cable is eliminated by shock absorbers at the upper end of the cable, at the same time pulling the pouch containing the mail bag out of the chute-like container attached to the side of the aircraft (source: here).

Fig. 14: Illustrations of the contemporary press (source: here).

Fig. 15: The seaplane catches up and overtakes the ADRIATIC (source: here).

Fig. 16. and 17: Above: The moment of the flight across over the ship and the release of the cable (source: here). Below: Illustration of the experiment in "Electrical Experimenter" magazine (source: here).

Fig. 16. and 17: Above: The moment of the flight across over the ship and the release of the cable (source: here). Below: Illustration of the experiment in "Electrical Experimenter" magazine (source: here).

Fig. 18. and 19.: Above: Shots of the mail delivery (source: here). Below: A letter from the mail bag of the first air-sea mail delivery (source: here).

Fig. 18. and 19.: Above: Shots of the mail delivery (source: here). Below: A letter from the mail bag of the first air-sea mail delivery (source: here).

The Aeromarine company benefited from the success of the experiment according to the plans of the owners: on August 21, 1919 (a week after the successful completion of the experiment), its flying boats were already carrying out civilian passenger transport (a New York businessman in a hurry was transported from New York to Poughkeepsie along the Hudson River and back), they undertook the same thing in October, but already between New York and Havana, and by the end of the year they also opened the first New York city sightseeing flights. The company grew rapidly: in 1920, it acquired the Florida-West Indies Airlines, and then entered into a contract with the government to deliver airmail to Cuba (this was the very first international airmail contract in US history). Aeromarine developed the AM-1, 2, and 3 types of aircraft to take advantage of rapidly expanding opportunities (such as the night flights for mail delivery).

Following the success of the experiment, White Star Line put forward the prospect of making the solution regular on its ships. Seeing the significant difference in speed between a fast airplane and a ship that only trudges along in comparison, some expressed the possibility that airplanes could soon make passenger ships obsolete in intercontinental traffic (as soon as they become capable of transoceanic flight). However, more sober-minded professionals already warned that ships will always remain indispensable in the transport of large quantities of bulk goods. Although they could not predict when the transition in passenger transport would take place (when the very first long-distance aircraft, capable of flying across the Atlantic Ocean and carrying many passengers at the same time could be built), but they declared that seaplanes certainly will be useful additions to the equipment of ocean-going passenger vessels.

They were right: it really happened that way. However, this is another story.

Fig. 20: Cyrus Johnston Zimmermann flies his plane directly opposite the ADRIATIC after catching up with her and just before starting the turn that ended with the successful delivery of the mail (source: here).

It would be great if you like the article and pictures shared. If you are interested in the works of the author, you can find more information about the author and his work on the Encyclopedia of Ocean Liners Fb-page.

If you would like to share the pictures, please do so by always mentioning the artist's name in a credit in your posts. Thank You!

Sorurces:

[1] Phillippa Stewart (2015): Barnstorming used to be way more dangerous…

https://www.redbull.com/gb-en/barnstorming-used-to-be-way-more-dangeros

[2] Stephen Kochersperger (2018): Airmail – a Brief History, https://about.usps.com/who-we-are/postal-history/airmail.pdf

[3] Sz.n. (1910): To Fly Aeroplane from Ocean Liner [New York Times, 3 November 1910], https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss46706.05003463/?sp=1&st=image&pdfPage=1&r=-1.293,4.345,3.586,1.633,0

[4] Dr. Greg Bradsher (2020): The First Aeroplane Take Off from a Ship, November 14, 1910., https://text-message.blogs.archives.gov/2020/08/11/the-first-aeroplane-take-off-from-a-ship-november-14-1910-part-i/

[5] M. C. Farrington (2016): How One Piece of FOD Changed Naval Aviation History, https://hamptonroadsnavalmuseum.blogspot.com/2016/11/how-one-piece-of-fod-changed-naval.html

[6] John Hammond Moore (1981): The Short, Eventful Life of Eugene B. Ely, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1981/january/short-eventful-life-eugene-b-ely

[7] Sz.n. (1919): Air mail delivered for First Time to Steamship at Sea, in.: The New York Tribune, August 15, 1919, Page 16, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1919-08-15/ed-1/seq-16/

[8] Sz.n. (1919): Delivering Mail to Steamer After It Has Sailed, in. Scientific American Vol. CXXI. No. 8 August 23. 1919, https://ia802308.us.archive.org/7/items/sim_scientific-american_1919-08-23_121_8/sim_scientific-american_1919-08-23_121_8.pdf

[9] Paul G. Zimmermann (1919): The Aeromarine Aerial Mail Delivery System, in. Aviation and Aeronautical Engineering 1919.10.15, https://ia903404.us.archive.org/23/items/sim_aviation-week-space-technology_1919-10-15_7_6/sim_aviation-week-space-technology_1919-10-15_7_6.pdf,

[10] Sz.n. (1919): Seaplane delivers Ship Mail at Sea, in. Electrical Experimenter, 1919.10., https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Archive-Electrical-Experimenter/EE-1919-10.pdf,

[11] Sz.n. (1920): The Log of an Aeromarine. A Modern Adventure in Pathfinding, https://www.blindhorsebooks.com/pages/books/16340/aeromarine-plane-motor-company/the-log-of-an-aeromarine-a-modern-adventure-in-pathfinding-aviation-history

[12] Sz.n.: Aircraft Journal 1919 August 23, https://www.reddit.com/r/Oceanlinerporn/comments/zml4t9/information_about_rms_adriatics_air_mail_delivery/#lightbox

[13] Waldemar Kaempffert (1919): How the Popular Science Monthly dropped Mail on a Liner’s Deck, in.: Popular Science Monthly, October, 1919, https://archive.org/details/sim_popular-science_1919-10_95_4/page/84/mode/2up

[14] Sz.n.: Photos of Aeromarine aircraft, https://www.timetableimages.com/ttimages/aerompha.htm#miami

[15] Biographies of Aeromarine personalities, https://www.timetableimages.com/ttimages/aerombi1.htm#czim

[16] Sz.n. (1919): A Pioneering Experiment in Shore-to-Ship Mail Delivery, https://transportationhistory.org/2023/08/14/1919-a-pioneering-experiment-in-shore-to-ship-mail-delivery/

[17] 1919 first airplane delivery, shore to ship at sea cover,

https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-c560-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Utolsó kommentek