White Star Line's last major effort was the design and construction program of the ocean liner OCEANIC (III), which was planned to be built between 1926-1929 but ultimately left unfinished. The ship would have been an unparalalled masterpiece if she had been built and - thanks to her unique propulsion system - she would have been such a huge advance for her time that she would not have been surpassed until the ocean liner QUEEN MARY (II) was entered into servie in 2004. This article is dedicated to her story.

I.) "Twilight of the Gods" - The TITANIC disaster, and the IMMC., the WSL and the H&W, 1912-1927

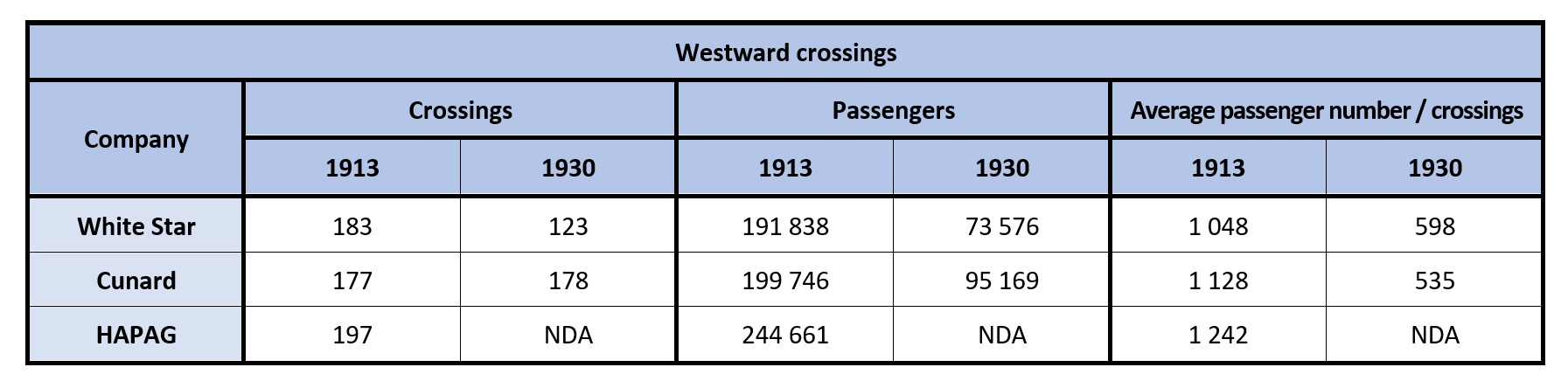

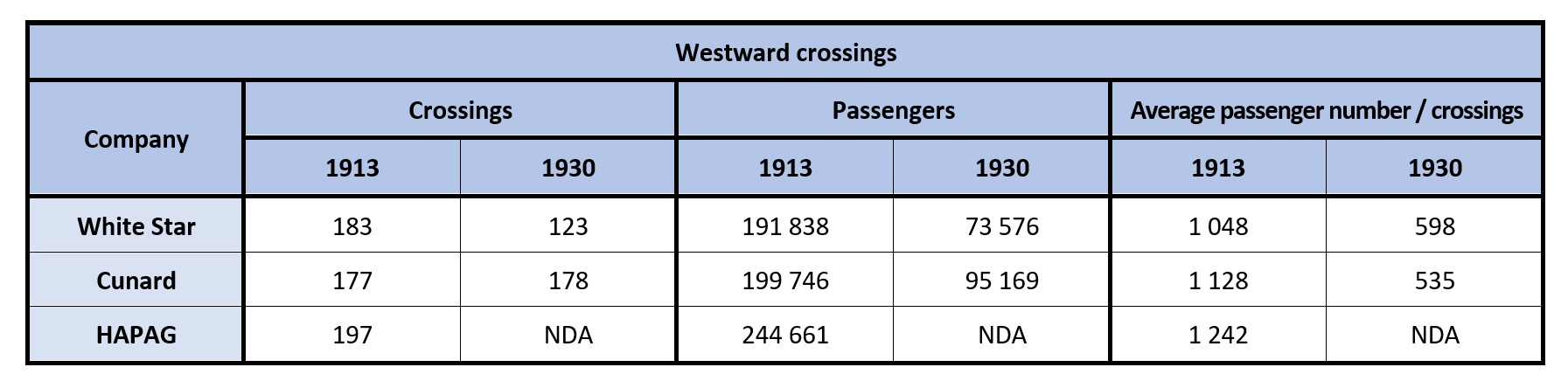

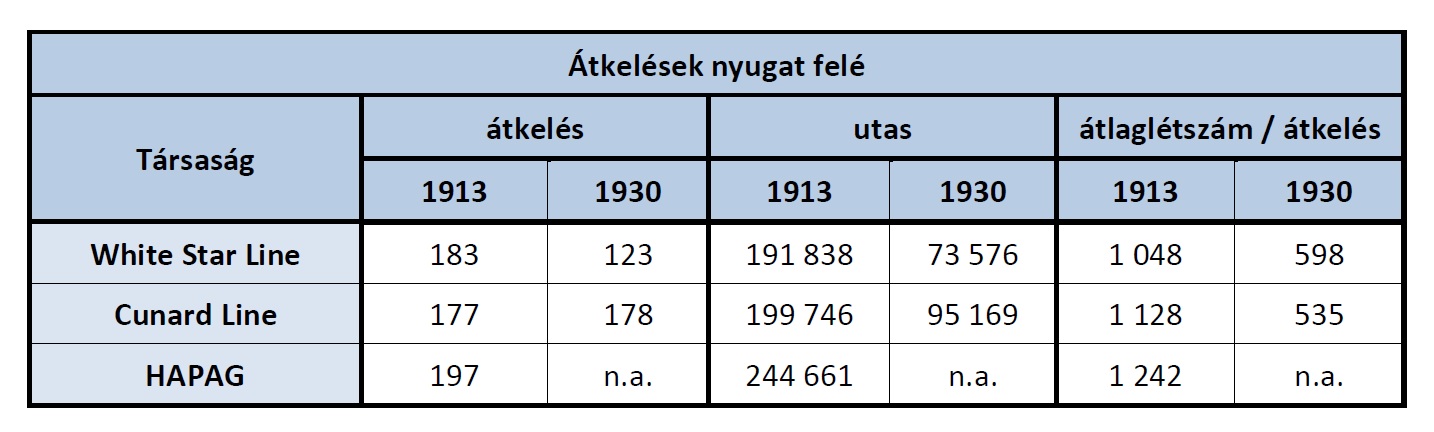

The majority of the shares of the British White Star Line shipping company, founded in 1867, were bought in April 1902 by the American financier John Pierpont Morgan, who announced the establishment ot the International Mercantile Marine Co. (IMMC) in October of the same year, that combined 7 shipping companies he owned. IMMC's fleet of 106 vessels accounted for 7% (30% including ships of the 2 partners and 1 joint venture) of the fleet of 1,555 vessels operating worldwide. 82 of the 106 ships belonged to the White Star Line, which was the only member of the group of companies that operated profitably in every year of the decade between 1904-1914 (in view of this, from 1904 the task of managing the entire IMMC was performed by the managing director of the White Star Line). The tragedy of the TITANIC occurred during the boom in passenger transport (the construction of the ship was also a result of it), which continued unabated despite the disaster: in 1913, more than 2.6 million passengers were transported across the Atlantic Ocean between Europe and America. This kind of traffic had never been achieved before, and it was never even approached again in peacetime. The White Star Line then carried 191,838 passengers compared to the Cunard Line's 199,746. White Star steamers completed 183 crossings, i.e. they transported an average of 1,048 passengers per trip, while Cunard completed 177 crossings, which means 1,128 passengers. The two British companies accounted for 7.3% of the total traffic, while the German HAPAG alone transported 244,661 passengers on 197 crossings (so an average of 1,242 passengers per trip), thereby obtaining 9.4% of the traffic. Although progress seemed unbroken despite the loss of the TITANIC, everything changed with the sinking of the flagship of the IMMC fleet. In addition to the human and material loss, the tragedy also affected the organization of the trust: As he had already decided before the sinking of the TITANIC - in January 1912 - J. Bruce Ismay retired from the position of president of the IMMC in 1913, where he was succeeded by Harold Sanderson. John Pierpont Morgan died in the same year, and in 1924 William James Pirrie, the owner and general manager of the giant shipyard serving the IMMC empire, Belfast's Harland & Wolff, succeeded him. The trust, in the form it had been known until then, had been declined.

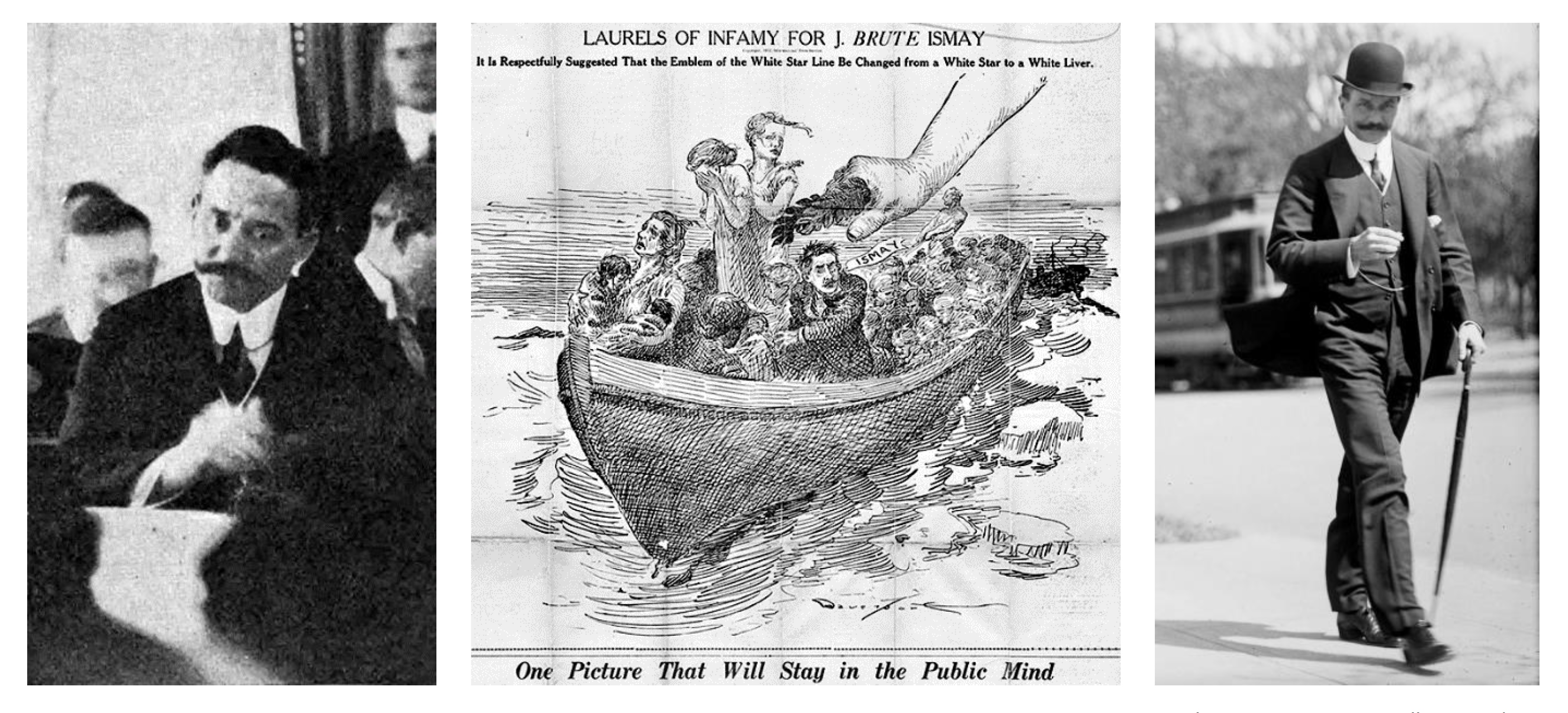

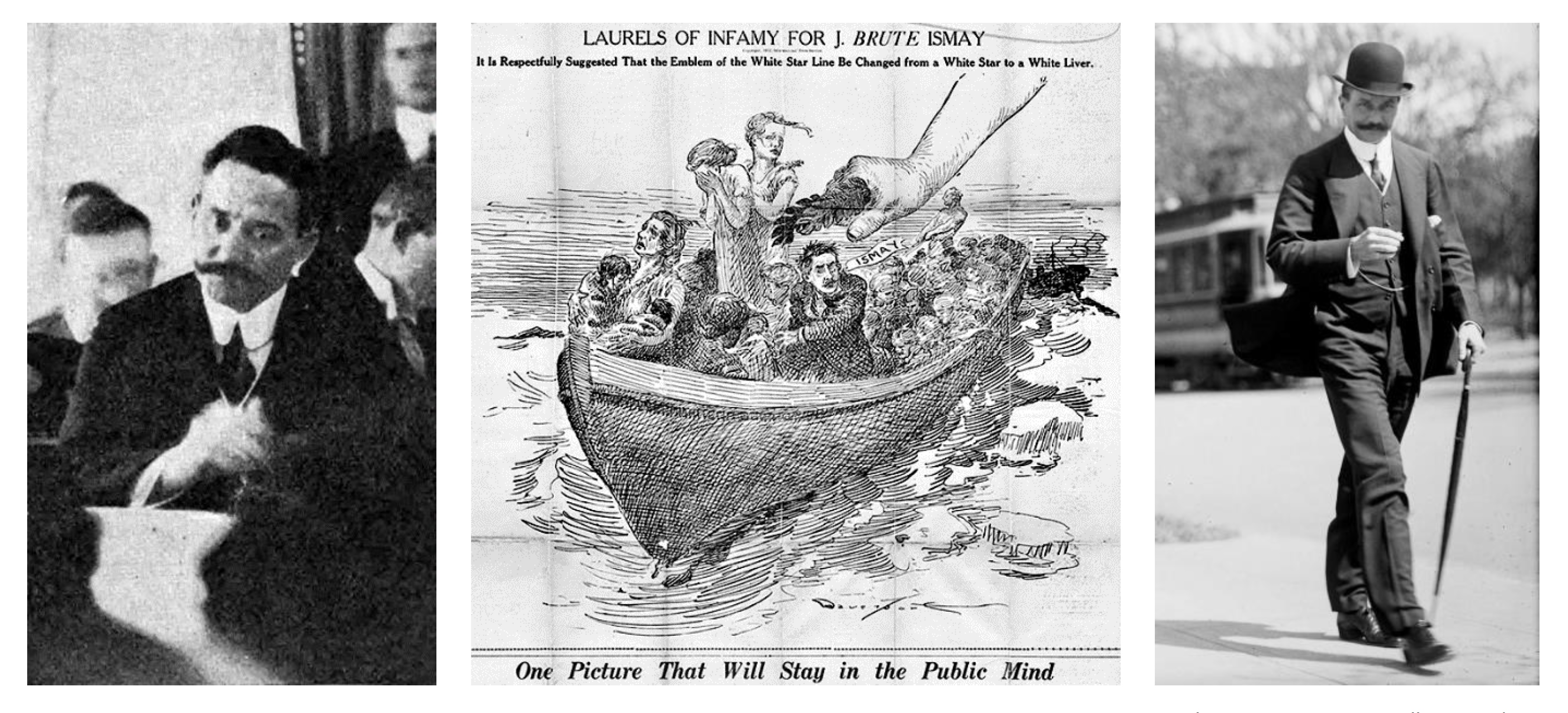

As for Ismay, he was labeled a coward and ostracized by London society despite the fact that, according to the commission investigating the circumstances of the tragedy, he helped many other passengers before finding a place for himself in the last lifeboat that left the starboard side of the ship. On December 31, 1912, Ismay therefore confirmed that, in accordance with his decision in January, he would resign from the post of president of the IMMC with effect from June 30, 1913. His decision was accepted on January 2, 1913, but his request to remain general manager of the White Star Line was rejected. He was succeeded in both positions by former Vice President Harold Sanderson. And Ismay remained a member of the board of directors of IMMC for another 4 years (in the British Commission chaired by Edward Charles Grenfell, the first baron of Saint Just, alongside William James Pirrie and Harold Arthur Sanderson), but when he finally gave up all hope of being elected to head the White Star Line again, he also resigned from this position in 1916. He never recovered from the shock caused by the TITANIC disaster and the subsequent American press campaign against him. Even before his trip on the TITANIC, he was emotionally insecure, but the tragedy pushed him into a deep depression from which he never truly recovered. Most of his work was then given to the cases of The Liverpool & London Steamship Protection & Indemnity Association Ltd (the insurance company founded by his father): Hundreds of thousands of pounds were paid out as compensation to the relatives of the TITANIC victims. Ismay handled the plight of the applicants with great fortitude, despite the fact that he could have easily shied away from responsibility and resigned from the board of directors of this company. Still, he persevered with the difficult task, even though during the remaining years of his presidency it is difficult to find even a single page in the papers of the company that did not mention the TITANIC. What's more: he donated £11,000 from his private fortune to create a relief fund to support the relatives of the many shipwrecked survivors, and in 1919 another £25,000 to support merchant seamen who served in the First World War. Although his wife, Florence, consistently made sure that the TITANIC was never discussed in the family again, it still haunted Ismay, who tormented himself with useless speculations about how he could have avoided the disaster.

Fig. 1: J. Bruce Ismay in front of the US Congressional Commission of Inquiry and in the US press as "J. Brute Ismay". (Source: Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. digital ID cph.3b15542, file no. LC-DIG-hec-00933, New York American)

At Christmas 1936, at a family gathering, one of his grandchildren, Evelyn, who had learned that Ismay had also worked in shipping, asked him if he had ever been shipwrecked. Ismay then broke his quarter-century silence about the tragedy that ruined his life and replied: "Yes, I was once on a ship that was thought to be unsinkable." On October 14, 1937, Ismay, who had already been suffering from diabetes for several years (whose right leg had to be amputated below the knee in 1936), suffered a stroke on October 14, 1937, as a result of which he lost consciousness, became blind and mute. He died three days later.

Morgan died in his sleep in his hotel room on March 31, 1913, during a trip to Rome. Corpse stake in s.s. FRANCE transported him back to New York, where the flags were lowered to half-mast and the stock exchange closed for two hours. His company empire was taken over by his son, John Pierpont ("Jack") Morgan, Jr., who did not have nearly as much influence as his father. Based on the antitrust laws, the company empire had to be divided into three smaller companies in 1933, but the shipping interests were no longer among them. IMMC was an over-leveraged company that borrowed too much money compared to its solvency (it also bought up the debts of its member companies), so it went bankrupt, when the news of the outbreak of the First World War caused prices to collapse and the group's solvency was shaken: in September 1914 the directors of IMMC announced that the October 1 interest payment on the 4.5% bonds would be postponed due to the disruption and uncertainty caused by the outbreak of war. The bond foreclosure stipulated that the six-month deferral would not constitute default, but by the spring of 1915, IMMC was bankrupt with $3.3 million in interest debt, and on April 3, a receiver was appointed in a person of Philip Albright Small Franklin, the White Star Line's representative in New York at the time of the TITANIC tragedy. After the years of bankruptcy trusteeship in 1915/16, he succeeded Sanderson as president of IMMC and was determined to save the group of companies. Under his leadership, the IMMC was able to recover when the war economy boosted shipping again (and despite the losses it suffered, the IMMC, which still had the largest fleet, was able to benefit the most from this, since its steamers accounted for a quarter of the entire American expeditionary force and nearly 15 million tons of munitions were delivered to France). By the end of the war, future trade conditions had become unpredictable, as North Atlantic liner shipping was affected by two circumstances that no one would have considered before the war. One was the elimination of the German ships confiscated as war reparations from the competition, and the other was the huge increase in the tonnage of American merchant shipping through the Emergency Shipbuilding Program and the seizure of German ships (the latter represented approximately 300,000 gross register tons of passenger space). For the first time since the dawn the Age of steam, the United States was in a position to challenge Britain's world dominance of maritime commerce, at least in terms of carrying capacity. However, IMMC found itself in an awkward position. After all, although he wanted to share in the expected renaissance of American shipping, most of his income came from the income of British ships it owned.

Fig. 2: The news of the death of J.P. Morgan - the "uncrowned king" of the stock market - in the American newspapers and Morgan at the White Star pier in New York at the arrival of the OLYMPIC on her maiden voyage in 1911. (Source: Morgan Library)

In the atmosphere of fierce nationalism that developed in the United States after the war, Morgan's promise in 1903 that he would "not pursue a policy injurious to British merchant shipping or injurious to British commerce" was effectively used to prevent the trust from purchasing ships in the United States. Thus, the paradoxical situation arose that the only American company that had enough capital, management experience, and agent network to manage European traffic, essentially could not participate in it. The IMMC was thus still maintained by the White Star Line, which, with the exception of 1917, maintained its Atlantic voyages throughout the war years (102 in 1914, 61 in 1915, 44 in 1916, 41 in 1918, 1919 and 47 passengers arrived to America on board of the company's ships). The scheduled Southampton-New York service was reopened in 1920 with OLYMPIC and ADRIATIC, for which they completed 37 crossings, carrying a total of 60,120 passengers - an average of 1,624 per voyage. At the same time, Cunard's steamers MAURETANIA and AQUITANIA completed 57 crossings with a total of 88,295 passengers (an average of 1,549 per voyage). Taking advantage of the respite to avoid another insolvency, the IMMC Act sold its foreign subsidiaries in the 1920s and 1930s. In 1920, they first bought all the ordinary shares of the Leyland Line that they did not yet own, then the steamers of the Red Star Line were also transferred to the property of the Leyland Line (they no longer operated under the Belgian but the British flag), while the names of the Dominion Line and the Red Star Line were kept for commercial purposes only. By 1924, the White Star Line - which was still the second largest passenger carrier on the North Atlantic - was already making a loss. This was related to the United States re-regulating immigration in 1924 and established quotas per ethnic group on the number of foreigners that can be admitted each year, the number of people who can still be accommodated in a given ethnic group in one year, which was maximized at 2% of the number of people belonging to the given ethnic group, according to the 1890 census data. All this had a drastic effect on emigrant traffic, so in 1926 the shareholders of IMMC accepted the British offer to buy back the White Star Line for the equivalent of 33.9 million dollars. The buyer was the Royal Mail Steam Packet Co., which took over in January 1927.

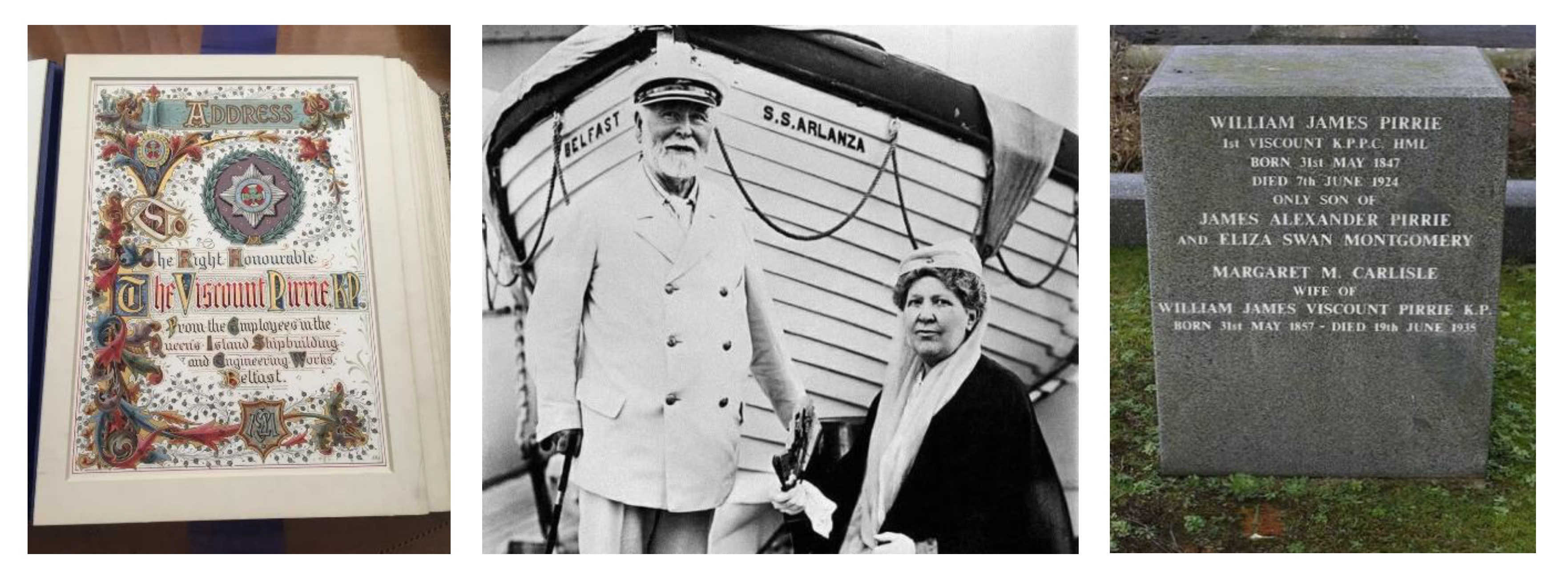

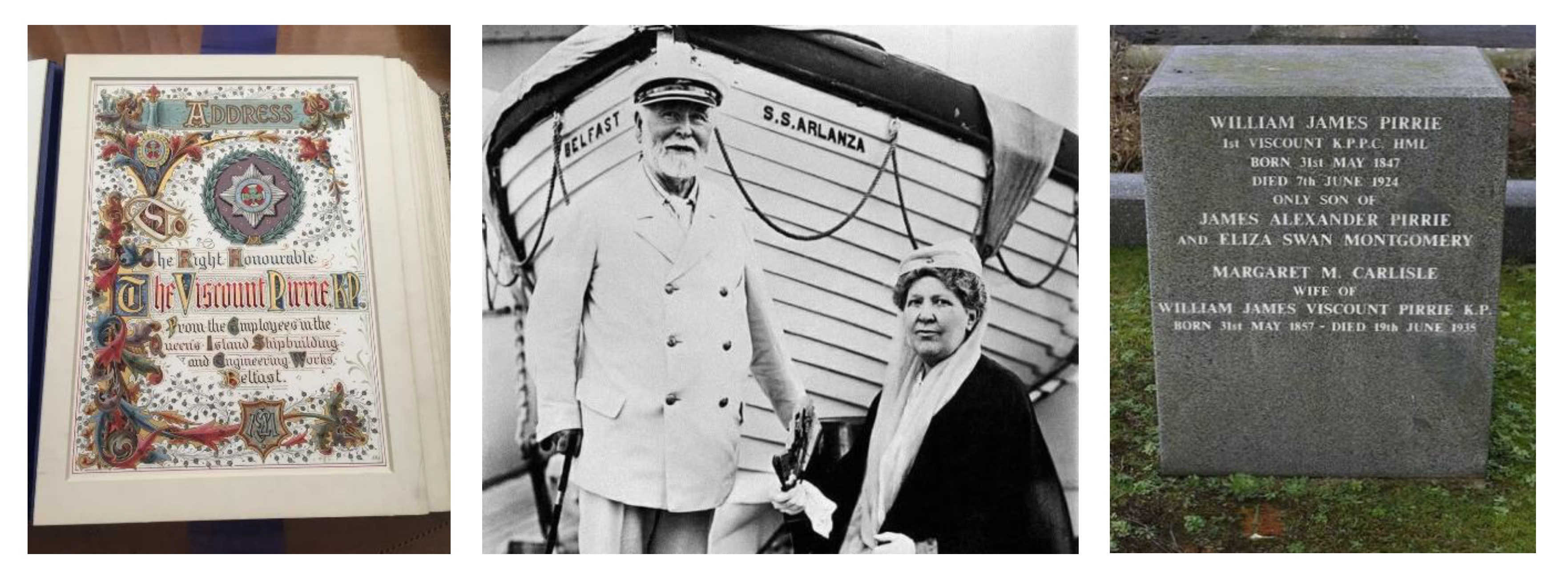

Pirrie and Harland & Wolff could not escape their fate either. Lord Pirrie was really in his element during the war years, as the Royal Navy heaped the shipyard with orders, but with the end of the war, the orders also dried up, and with this Pirrie felt that his position within the company was shaken. He tried to demobilize disobedient workers with social measures - the establishment of recreation parks - and the higher-ranking workers were still fairly regularly given gifts by his wife every Christmas. The first signs that all was not well came when they discovered that the directors were holding their own event in 1920, separate from the Pirrie couple's Christmas party. Pirrie didn't want to stay away from the affairs of the shipyard even for a minute, so he kept putting off taking the advice of his doctors, who had been recommending long-term rest for a long time. He finally gave in in the spring of 1924, when he agreed to go on a tour of South America and Europe with his wife to assess whether the infrastructure of the ports of the countries concerned was developed enough to serve the ships of the yard's largest partners, the Royal Mail Line, Pacific Steam Navigation Co. and Lamport & Holt Line companies, and can also take a summer and winter trip, combining the comfortable with the useful. On March 21, they left for Buenos Aires on board the ARLANZA Royal Mail liner built by Harland & Wolff and from there they extended the trip to Valparaiso, Chile by going around Cape Horn. While they were waiting for the connection in Valparaiso, Pirrie caught a cold, and the cold soon turned into pneumonia. They sailed from Antofagasta on board the EBRO towards the Panama Canal. Pirrie was already convalescing when they reached the canal, and against the advice of his doctors, even on his sickbed in his usual dictatorial manner, he ordered to be taken on board because he wanted to see the canal. It was a fatal decision. Despite the heroic struggle of the ship's medical and nursing staff, the 78-year-old shipbuilder died on the night of June 7, 1924, at 11:30 p.m. When EBRO arrived in New York, his embalmed body was transferred aboard his masterpiece, the OLYMPIC, which took him to Europe (he was given what Morgan was not, whose powder pod was only transported as a piece of cargo in the refrigerated hold of a ship that didn't even belong to the huge ocean-going fleet he created). He was laid to rest in Belfast on June 23, 1924, the day he joined the company's workforce 62 years earlier. He did not make any preparations for his retirement or his death, so the members of the board of directors did not even know what new tonnage construction he was discussing before the trip started. He took his secrets, if any, to the grave, as his ambition and exclusive management style blinded him to training his directors in the methods he used to acquire business and manage the company. He surrounded himself only with people who tried to imitate his lifestyle, but were weak to contradict him: George Cuming was dead, Edward Wilding was suffering from a nervous breakdown (Pirrie took back direct control of the drawing office tasks at his expense in February 1924), and Robert Crighton was also ill; John Westbeech Kempster was a nice old gentleman who spent more time in the university cloister than in the business world, J.P. Dickinson, the manager of the Govan site, was incompetent and weak, and Charles Payne from Belfast was a showman. Among the directors, only F. E. Rebbeck had the necessary skills, but he was regularly voted out by his senior colleagues. Apart from him, only William Tawsee, the chief accountant, and John Phillip, the chief executive's secretary, had any idea of what and how Pirrie was doing. In any case, all directors agreed that the position of president and CEO held by Pirrie would be abolished and the management of the factory would be taken over by the board of directors. Having only a sketchy knowledge of the factory's finances and knowing nothing about which of the oral negotiations on new constructions had led to results, the members of the board of directors could not rise to their responsibilities. Harland & Wolff, the largest shipyard in the world, was left without effective leadership on the brink of its biggest economic crisis...

Fig. 3: 'Lord Pirrie's Book' – a gift from the shipyard workers to Pirrie on his 1921 ennoblement (left), Pirrie and his wife at the start of the fatal voyage on the steamer ARLANZA (centre) and Pirrie's tombstone in Belfast (right). (Source: Maritime Belfast Trust, Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, J146580607, Find a grave/Paul Fryer)

II.) Lord Kylsant, the new favorite:

However, the Harland & Wolff Shipyard soon had a new owner. Namely, the same man who was behind the repurchase of the White Star Line into exclusive British ownership: Owen Cosby Phillips (1863-1937), 1st Baron of Kylsant.

Owen Phillips was born in the rectory at Warminster, Wiltshire, the third of five sons of Rev. Sir James Erasmus Philllips - 12th Baron of Picton Castle - and his wife Mary Margaret Best. After his schooling in Devon, in 1880 he entered the Dent & Co. Shipping Company in Newcastle upon Tyne as an apprentice, and in 1886 he joined the Allen Line in Glasgow. In 1888, he founded his own shipping company under the name Phillips & Co. with the financial support of his eldest brother, John Phillips. Their first ship was purchased in 1889, but by 1900 the two brothers owned two shipping companies (the King Line and the Scottish Steamship Co.), an investment company (the London Maritime Investment Co.), and the London and Thames Haven Petrol Port. In 1902 - when J.P. Morgan bought the majority of shares in the White Star Line - taking advantage of the low share prices, the Phillips brothers also acquired a dominant share in the Royal Mail Steam Packet Co. (RMSPC), of which 39-year-old Owen Phillips became the president and managing director.

RMSPC was founded in 1839 by the Scotsman James MacQueen, and originally transported mail and passengers to the ports of the Caribbean and South America with the firm intention of supporting the abolition of slavery in the British colonies of the Caribbean by launching the first steamship in the region. The government trying to master political and social instability through British economic hegemony in achieving its goals. The support was generously rewarded by the government - with a subsidy of £240,000 per annum - which provided ample funding for RMSPC to grow into one of the leading companies in British shipping, both financially and technically (a convincing example of the latter being that RMSPC was the first British shipping company to equip its ships with compound steam engines developed by John Elder in the 1850s and perfected since then in the 1870s). Between 1902 and 1922, under the management of Owen Phillips, the RMSPC acquired a decisive share in more than twenty other shipping companies, including those such as the Union-Castle Line, which ran to the British colonies in Africa, or the Peninsular & Orient, which maintained maritime links with the Far East and Australian colonies. (P&O).

Owen Cosby Phillips was also a Member of Parliament between 1906-1922 (between 1906-1910 for the Liberal Party for Pembroke and Haverfordwest, and between 1916-1922 for the Conservative Party, as a delegate for Chester). In 1922, he received a knighthood (he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George), and in 1923 he was ennobled, when the king made him the first baron of Kylsant, and awarded him with the Commander's Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George. From then on, Phillips participated in the legislature as a member of the House of Lords. Owen Cosby Phillips did not meet William James Pirrie for the first time here, as they had been in contact since he first ordered ships for his company from Harland & Wolff as the President and CEO of RMSPC. Between 1904 and 1916, 17 ships of the company were built in Belfast, while only 15 ships were built for the White Star Line (Oceanic Steam Navigation Co. - OSNC) in the same period[1]. This made Phillips Pirrie's most important customer. It is therefore hardly a coincidence that already in 1914 Pirrie stated as part of a private conversation with Edward Holten that according to his plans after his death "Phillips will be in charge of everything".

Apart from the fact that Kylsant owned the majority of Harland & Wolff's shares from 1919 onwards, the similarity of the two men's uncompromising, violent and autocratic characters, which made him appear much more suitable from the beginning, therefore made him more sympathetic in the eyes of Pirrie, who perhaps saw him as a first-generation "empire builder" similar to himself (as Pirrie liked to see himself, generously forgetting that his shipyard, of which he was so proud, was created by Sir Edward Harland's engineering knowledge and Gustav Wilhelm Wolff's financial prowess). Bruce Ismay, who was born with a silver spoon and inherited his business empire from his father, was not respected by Pirrie, which is clearly shown by the fact that he did not let him know when he started negotiations with J.P. Morgan about the sale of White Star Line behind his back. (Perhaps it was precisely for this reason that he later prevented his return to the head of the White Star Line, as he was able to personally see that Ismay was a man from whose hands even the family company had been wrested out. He apparently did not care that this could not have been done without him.)

It is not known how seriously Lord Pirrie thought about having Lord Kylsant manage the Harland & Wolff Shipyard after his death, as he did not shared the content of his conversation with Edward Holten to either the vice-president, Robert Crighton, or to his lawyer, Charles Crisp. At the meeting of the board of directors of Harland & Wolff Shipyard held three days after Pirrie's death, something happened however, because Pirrie's London office with all its accessories was available to Kylsant within days, where he declared himself the new president and CEO of Harland & Wolff Shipyard. We are hardly disappointed if we guess the fear of responsibility of the largely incompetent board members selected by Pirrie in the background. As Crighton (himself reluctant to take on the chairmanship) reminded the board members: 'hitherto Lord Pirrie has been approached individually to do certain works, to adopt certain policies, or to authorize various expenditures, but in future all must consult the with others because of the shared responsibility". Of course, Lady Pirrie must have known of her husband's intention (if he had such an intention), but in any case she was in no hurry to confirm it, as she disliked the lord of Kylsant. He found her arrogant and aloof, although she believed that this had more to do with Phillips's extraordinary height of more than 2 meters, his maypole appearance and his stammer, rather than his deliberate attitude towards her. At the same time, she steadfastly avoided being seen in the company of either Kylsant or his wife.

Despite this with a generous gesture, Kylsant offered Lady Pirrie the position of chairman of Harland & Wolff for the entire period of her life. Nevertheless, Lady Pirrie wanted Lord Inverforth to be elected as president (mistakenly thinking that as administrator of the Pirrie estate and her husband's heir, she also had a decisive say in corporate decision-making, which had not been the case since 1919, since, the majority of the shares were owned by Kylsant). Kylsant's first task was to investigate the shipyard's finances. While Pirrie was first and foremost an engineer with a thorough knowledge of every sub-process of shipbuilding, who had the attitude that "whether for profit or loss, it doesn't matter, just let the shipyard produce", Kylasnt was primarily a financial specialist who (even though he worked with shipping companies) did not have a similar background knowledge in shipbuilding, but - perhaps influenced by the upbringing of his father, who held an ecclesiastical profession - he threw himself into the business with an almost missionary zeal, seeing it as his moral obligation to give work to people (who respected him for this in the midst of the ever-increasing unemployment situation). However, he quickly saw through the disastrous finances of Harland & Wolff: Pirrie's generous way of life almost brought the company to financial ruin. He overdrawn his line of credit with the Midland Bank, for which he offered the Witley Court estate as collateral, worth some £325,000, and undertook to personally buy back £473,260 worth of Harland & Wolff preference shares from members of the Colville family. His most important financial assets were the shares he owned in the Harland & Wolff Shipyard and in the Elder Dempster shipping company. However, Kylsant knew full well that these would not provide any serious dividends to shareholders in the near future (not even the annuity due to Pirrie's testamentary heirs could be paid from them). The company's finances looked so bleak that Kylsant's first reaction was to suggest to the estate's trustees that they file for bankruptcy (which would also have allowed them to ignore Pirrie's will, which was to take the privately owned shipyard public—that is, shares for public trading on the stock exchange - and stipulated the mandatory continued employment of the directors for that case). Kylsant was only willing to desist from this intention at the persuasion of Pirrie's two closest friends - Lord Inchcape and Lord Inverforth.

Fig. 4: Lord Kylsant (painting by Philip Tennyson Cole in Carmarthenshire County Museum).

Inchcape reasoned that surely Kylsant didn't want the bankrupt widow to cause him various inconveniences as she traveled around London. Kylsant thus finally persuaded the boards of directors of the companies previously owned by Pirrie to combine the annuities for Lady Pirrie and the other beneficiaries of the will. However, the biggest concern was not Lady Pirrie, but Harland & Wolff's finances, which were in an shocking state.

As an experienced investor, Kylsant was horrified by the shipyard's fragile financial situation, as he clearly saw that the demands for repayment of unsecured loans would not be met if the creditors demanded them at the same time during a possible crisis. The danger was not just a theoretical possibility at all, since the John Brown Shipyard had already submitted a claim for unpaid debts worth 252,000 pounds, but before the end of the financial year there was no other option than to cover up the serious situation. In particular, Harland & Wolff actually made a loss with every ship it delivered. With the steamers KATHIAWAR and INVERBANK recently built in Govan, £160,000, but even after the ocean liners MOOLTAN, MALOJA and MINNETONKA, the income was only 4% of the total purchase price, which was also taken into account in the previous year's closing accounts. The payment of the depreciation provision of £224,013 was again deferred, bringing the total shortfall to £643,173. The repayment of the interest on the loans was also postponed, while the nearly £262,000 in dividends could only be paid by borrowing another £360,000. This increased the company's total loan stock to nearly £3,000,000. All this was shown in the annual financial statement presented to the shareholders under the heading "Miscellaneous creditors, including bank overdrafts" together with a further £240,000 which was shown as a reserve under "Miscellaneous extraordinary accounts and pending sums". However, Kylsant knew exactly that he could not be smart forever, and the misery of Harland & Wolff could bring the entire Royal Mail empire to ruin.

Fig. 5: Lord Kylsant (centre), Duchess of Abercorn (left), Charles Payne (right) and Lady Kylsant (far right) in company on July 7, 1925, at the launching ceremony of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Co. ocean liner ASTURIAS, in Belfast (Source: Moss and Hume, p. 246.).

Kylsant therefore tried to run forward and, terminating the private nature of Harland & Wolff Shipyard, decided to take it to the stock market in order to stabilize the company's finances, which had been shaken by the abnormal management of the previous period, by involving publicly available investor capital. However, the share subscription that started on July 4, 1924 did not bring the expected results: out of the 4,000,000 pounds worth of 6% preference shares issued (with a face value of 1 pound) - as a result of the devastating news about other shipyards and machine factories - only 750 000 pounds of shares were subscribed (just under 19% of the total stock package). After the failure, the board was left with no other option than to introduce new operating and tender procedures to reduce overheads and boost competitiveness (as virtually no one knew the full details of the previous negotiation and pricing procedures introduced by Pirrie). Meanwhile - between the beginning of February and the end of August 1924 - Harland & Wolff received orders for a total of 10 new ships, but the construction of only 1 of these ships, Belfast Steamship Co.'s 9,000-ton steamer APAPA, did not result in a loss. During this period, the shipyard practically only received orders to retain workers. Kylsant held the first meeting of the board of directors between January 8-10, 1925. Revealed that the directors leading individual departments had handled the general and development costs with excessive carelessness until now. When Kylsant asked, for example, how the construction of the two large ocean liners for P&O (the MOOLTAN and the MALOJA) could have been unprofitable, he was met by the directors only to blame Pirrie's high quality expectations. After that, it was decided to explore all indispensable expenses, to reduce or freeze wages, and to reduce stocks by 25%, but no one could draw the conclusion that the Queen's Island site might have to be closed for a while. The cost reduction also resulted in a saving of only 25,000 pounds per year, the 1924 closing accounts had to be cosmeticized in this way: the annual income of 307,392 pounds on paper was then supplemented with 380,000 pounds transferred from the published company reserve, which thus hid the factory's 600,000 important loss. Despite Kylsant's best efforts, the final accounts were also evaluated by Price Waterhouse & Coopers, the shipyard's auditor, and stated the following: "depending on the adequacy of the reserves, we believe that the balance sheet has been properly drawn up to give a true and fair view of the state of the company's affairs give a correct picture”. This meant some respite…

It turned out to be an encouraging turn for both Kylsant and Harland & Wolff when, in August 1925, the White Star Line came forward with an order for the construction of a new, large ocean liner. Back in 1922, Pirrie suggested to Kylsant that he buy back the patina shipping company (who knows, maybe it hurt his British pride that Harland & Wolff could only become the world's largest shipyard by American capital, and by the transfer from British to American majority ownership of its biggest customer, White Star Line, of which it was the main shareholder, what might have disturbed his conscience, so he wanted to retrieve his honour). However, Kylsant's purchase offer at the time was personally vetoed by US President Warren G. Harding. In 1926, the British shipping company Furness Withy & Co. also came forward with a purchase offer. (Sir Cristofer, the first baron of Furness, the owner of Furness Withy & Co., founded in 1891, requested government support in 1900 in order to establish a British counter-combinate against the Americans initiated by J.P. Morgan, without success. After his death in 1912, the Furness family sold their interests in the company in 1919 to a consortium led by the former managing director, Frederick Lewis.) The agreement was reached, but the contract contained a stipulation that the contract was invalid if a general strike breaks out in Great Britain before the sale is completed. Although the biggest work stoppage of the 1920s - which was announced by the unions due to the continuous deterioration of the situation of coal miners and in order to stop the reduction of wages - only held between May 4-12, 1926., thwarted the hopes of the Furness company. Kylsant then re-entered the scene and by November bought all the shares of the White Star Line, together with all its financial and other assets, for which he paid a total of 33.9 million dollars, i.e. 7 million pounds at the 1926 exchange rate. Taking into account the financial deterioration that had occurred in the meantime, this means that the company was bought back for less than half of its 1902 purchase price (J.P. Morgan paid £10 million for the White Star Line in 1902, which was worth 20 million pounds at the exchange rate of 1926).

III.) New ocean liner designs in the 1920s and their impact on the White Star Line

When Harland & Wolff, taken over by Lord Kylsant, began to design the latest ocean liner of the White Star Line, which returned to exclusive British ownership, its construction has been on the agenda for more than a decade (with technical content redefined and redefined periodically according to the ever-changing needs), as the White Star Line had been considering the construction of a large new ocean liner since 1914.

What's more, on July 9, 1914, the giant steamer for the Liverpool-New York route, considered the second most important in the company's business policy, began to be built at the Harland & Wolff Shipyard, with production number 470. The ship was first named GERMANIC, after a successful ship built for the White Star Line in 1875 (sistership of BRITANNIC I), which left the company's fleet during the construction of the TITANIC (when it was also sold to the Ottoman Empire, where it was entered into service as GÜLCEMAL), so her name became usable again. Since this was the first ship to be built for the White Star Line after the loss of the TITANIC, many people think that its task was to replace the lost TITANIC, but this is contradicted by its technical data and intended use, which the IMMC's 1913 annual business report and IMMC director Harold Sanderson's June 1914 press statement make it clear beyond any doubt. According to the report: "Directors have authorized the construction of a steamer of about 33,600 tons and 19 knots speed for the New York-Liverpool service of the White Star Line, to be named GERMANIC, and to be of the ADRIATIC type, with such alterations and improvements as experience has suggested and as are made possible by her greater size. It is expected that the GERMANIC will be completed in time to enter the service in 1916, and that she will be an exceedingly attractive steamer” more spacious than before - equipped with private bathrooms, with finer furnishings - first-class accommodations and a larger swimming pool. Sanderson's statement went into further detail: "She will be a larger ship than the ADRIATIC but would be smaller than OLYMPIC." Her length overall would be about 746 feet and 88 feet wide (that is, her gross tonnage would have exceeded that of the LUSTIANIA and MAURETANIA), and she would have been fitted with three propellers, the two extremes of which would have been driven by reciprocating steam engines, the middle by a low-pressure steam turbine, that is, the In all likelihood, the ship was planned to be built based on the first preliminary design for the OLYMPIC-class, but nothing came of the plans: The name of the ship was changed from GERMANIC to HOMERIC at the outbreak of the First World War, and then at the end of 1914 the double bottoms completed until then dismantled to make way for urgent naval orders on Falcon Square. On May 27, 1916, the ship's keel was laid down again, but on May 13, 1917, the construction was interrupted for the second time - this time for good - and at the end of August 1917, they began to dismantle the hull that had been completed until then.

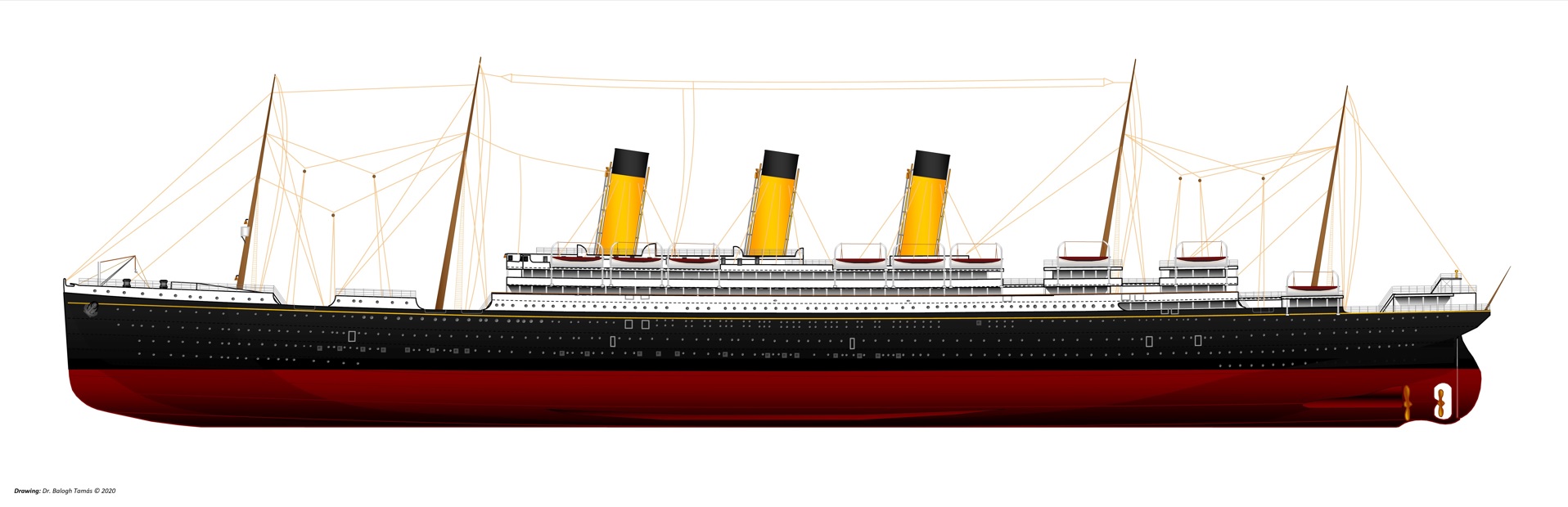

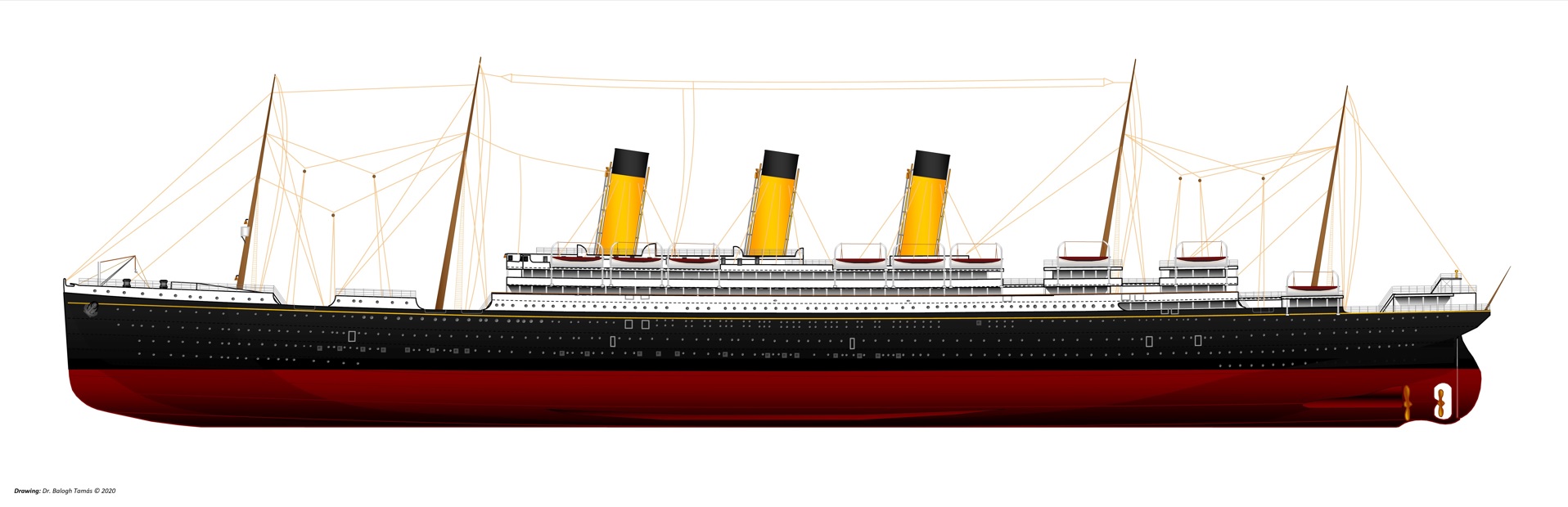

Fig. 6: The first draft of the OLYMPIC class from June 1907. Perhaps this design - which also evokes the main characteristics of the ADRIATIC - was considered as a basis for the design of GERMANIC. (Drawing by Dr. Tamás Balogh).

The second occasion took place already after the First World War, when Philip Albright Small Franklin, president of the IMMC, announced in 1919 that, as part of the White Star Line's post-war construction program, a new 35,000-ton ship would be built at Harland & Wolff " with a speed of 21 knots, and each cabin on the two upper decks has its own bathroom". Since the features mentioned in the announcement are very similar to those of the HOMERIC (ex-GERMANIC II.) built during the war and then abandoned (35,000 tons compared to 33,600 and first-class cabins with private bathrooms), it is hardly an exaggeration to assume that In 1919, they did not announce a brand new ship design, but that they would start again and this time try to complete the project, which had been forced to be interrupted in 1917. Soon, however, this plan also failed, this time due to war reparations.

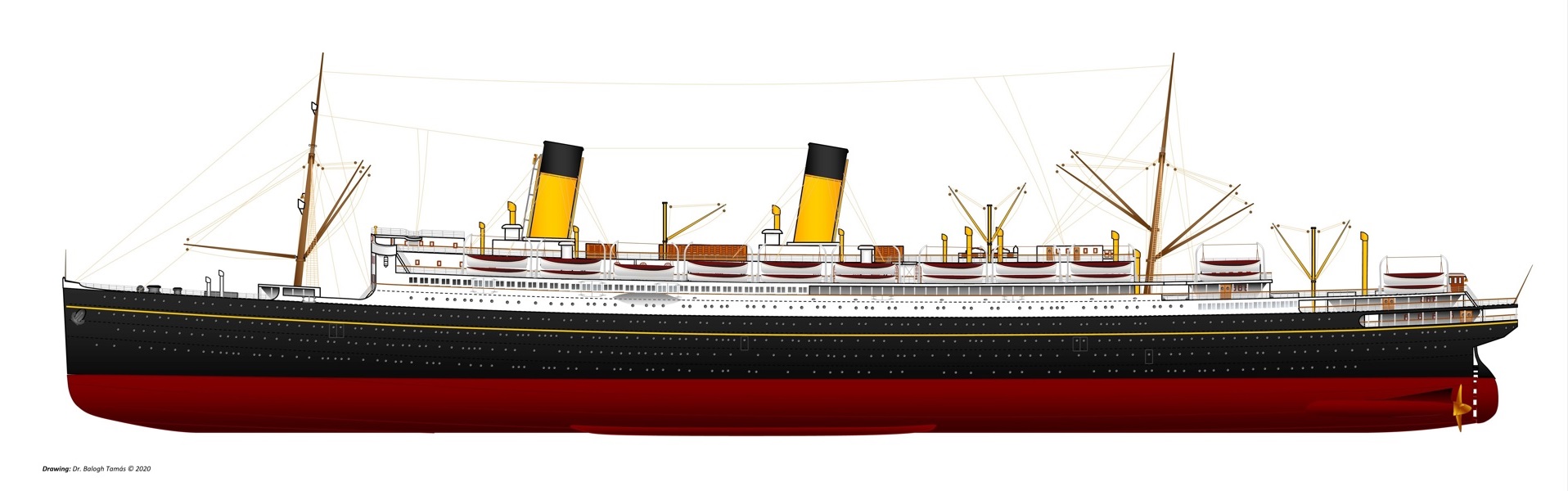

Fig. 7: The R.M.S. HOMERIC (ex-COLUMBUS), 1913-1935 (drawing by Dr. Tamás Balogh).

Due to the sinking of the TITANIC and then the GIGANTIC (later BRITANNIC II.), the new express service planned by White Star Line with the OLYMPIC trio could only be realized after the First World War, when the German ocean liners MAJESTIC (ex-BISMARCK) and HOMERIC (ex-COLUMBUS), seized as war reparations, replaced the sunken ships. The size of the 34,000-ton COLUMBUS just matched the size category of the previously designed ships, but it was driven by only two propellers, which were moved by piston steam engines (making COLUMBUS the world's largest ship powered by a conventional steam engine). As the ship was still half-finished in Danzig, Germany (now Gdansk, Poland) when it was handed over to the White Star Line, its completion could only take place a year later, at the end of 1921, and the first voyage could not be started until February 15, 1922. The White Star Line's biggest rival, the British Cunard Line, was also needed seized tonnage to able to maintain its three-ship service with seized ship - the BERENGARIA (ex-IMPERATOR) - which was put into service alongside MAURETANIA and AQUITANIA to compensate for the loss of LUSITANIA. While MAJESTIC surpassed BERENGARIA's speed (23.9 knots against 20.4 knots) and OLYMPIC competed relatively successfully with AQUITANIA (21.4 knots against 23.1 knots), HOMERIC's 18.1 knots speed was far below the MAURETANIA's average speed of 23.9 knots typical of the 1920s, so even though she was a newer and larger ship, fewer passengers bought tickets for her. By 1926, the differences became obvious: in the MAJESTIC-OLYMPIC-HOMERIC trio, MAJESTIC carried 50% of all passengers, OLYMPIC 33%, HOMERIC 17% (MAJESTIC transported as many passengers in its first 4 years of its service as HOMERIC did during its entire service period up to 1935). On the Southampton-New York route, the HOMERIC competed in a service for which, compared to her competitors, she was not suited, so it became clear to White Star Line that they needed another new ship of at least comparable performance to the OLYMPIC but more to the MAJESTIC.

What this new ship should be like, it was defined by the design starting points of the era. In the period between the two world wars, three circumstances had a fundamental impact on the design and construction of ocean liners: 1) the transition from burning coal to burning oil, 2) the entry into force of American immigration laws and the corresponding change in travel habits, and 3) the use of diesel-electric motors as the main engine of large ocean liners.

1) Transition from coal to oil burning

The liquid fuel that was first used to generate heat in ship boilers was petroleum produced by distilling crude oil, either in its original crude form, but more often in its syrupy (viscous) black tarry form after refining (so-called: "C-type bunker oil"). The calorific value of the fuel is characterized by the amount of heat that can be extracted from 1 kg of fuel (without the heat of vaporization of the amount of water leaving in the form of steam together with the flue gases), its unit of measure is MJ/Kg (Megajoule / kilogram). While the calorific value of coal used for ships was 14.24 MJ/Kg, that of contemporary heating oils was 19.51 MJ/Kg (5.4 kWh/kg).

The first ships equipped with oil-burning boilers - made by Spakovsky - (on which oil was injected into the combustion chamber of the coal-burning boilers as a combustion accelerator and heat enhancer), the cargo ships IRAN and CONSTANTINOPLE, were put into service in Russia on the oil-rich coast of the Caspian Sea in 1870 in , and then the vessel KHIVENYEC of the Caspian Sea fleet of the Tsarist Russian Navy was converted to oil-burner in 1874. They also burned a low-quality crude oil derivative that was left over as a by-product of oil refining - called mazut - but available in large quantities and cheaply (15 oil refineries were operating on the Abseron Peninsula near Baku, so mazut was an easily accessible fuel). The first ocean-going ship to be equipped with boilers available for oil-burning as well was the British tanker S.S. BAKU STANDARD sailing between Newcastle and New York in 1894, and the first ship equipped exclusively for oil-burning was the destroyer HMS SPITEFUL after she converted to oil burning in 1904. The very first ocean liner to cross the Atlantic using oil was the American-Belgian Red Star Line ocean liner KENSINGTON, created to transport American crude oil to Europe, in 1903.

Oil-burning in shipping had several significant advantages compared to coal-burning. On the one hand, the hydrogen content of oil is 11% higher than that of coal, which results in a much higher calorific value. On the other hand, liquid oil can also be stored in places on the ship where coal is not (e.g.: in the double bottom, in the narrowing space in the underwater parts of the bow and stern, etc.). In addition, the continuous oil injection kept the combustion of the oil (and thus the vapor pressure) constant and provided uninterrupted heat development throughout the journey (unlike the combustion of coal, which had to be interrupted while the resulting ash was removed). The handling of the oil involved much less time, noise and pollution, and required a much smaller staff. After all, while on a coal-fired ship 1 heater could attend to a maximum of 3 furnaces (i.e. 1 boiler), on an oil-burner ship 12 (i.e. 4 boilers), with much less physical work (on an oil-fired ship, all the work processes of fuel handling are 75% compared to a coal-fired ship)! With this, an average of around 200 members of the crew of a large ocean liner became dispensable.

The savings in labor and fuel costs more than covered the costs of the conversion investments. The conversion of coal-burner ocean liners to oil-burner ones primarily required the conversion of boilers and former coal bunkers. In the latter, the convex-headed rivets had to be replaced with smooth-headed ones in order to create a completely leak-free space, in which heaters had to be installed in order to prevent the oil from thickening due to cooling. In addition, the walls of the tanks had to be modified in such a way that they could withstand the hydraulic shock that might occur with the drop in the liquid level. However, there was no need to build new storage facilities, since much less oil was needed to travel the same distance compared to coal. The average time required for such a transformation was about 8 months.

Fig. 8: Stokers and trimmers in the boiler room of a coal-burner ocean liner in 1910 (left) and the boiler room of NORMANDIE in 1936 (right). The often illiterate members of the coal-dusted "Black Gang" were replaced by fuelmen, trained mechanics in white (!) overalls. The engine and boiler room personnel were reduced to a tenth and hundreds of thousands of people were lost their job and put on the streets in the course of a few years. (Sources: Richard P. de Kerbrech, Gamma-Keystones/Getty Collection, K006377-A4)

The solution therefore had many advantages, despite this, it had to wait from the 1870s until the 1920s before it became widespread. There were several reasons for this: on the one hand, obtaining oil outside the Caspian Sea was expensive at first (until the discovery of the American oil fields), and on the other hand, the efficiency of early burners remained low for a long time. Oil as a general fuel for commercial shipping thus only really spread with the development of marine diesel engines. By the second half of the 1920s, however, most ocean liners were converted to oil-burning. As a result, many of the masses (the former stokers and trimmers) who went out on the streets and were left without jobs and their ability to pay (the disappearance of the demand they generated) were later considered by many to be a sign and one of the causes of the Great Depression of 1929...

2) Changes in travel habits

In 1926, Major Frank Bustard, director of passenger traffic for the White Star Line, gave a lecture at the Liverpool Commercial School on the six classes of service offered on North Atlantic passenger ships, adapted to the identified needs of passengers. According to this, the services of ocean liners are usually used by passengers with the following needs:

„a) First class by the express steamers from Southampton, used particularly by businessmen and others to whom time is of monetary consideration; also by members of the theatrical profession and film industry who, for publicity purposes, cannot afford to travel other than in the ‘monster’ steamers.

b) Some of the companies are still running similar steamers, though not quite so large or fast and at slightly lower rates, from other ports, especially Liverpool. Their patrons atre mainly business travellers and the American tourist class, to whom time is not of primary importance and who have learnt by experience the estimable sea-going qualities that prevail on the type of steamer of 20.000-30.000 tons making the passage to and from New York in just over a week.

c) Cabin class. This class is supported by mainly passengers who formerly travelled First class, but who desire to combine economy with their travels, and there are also many travellers who previously crossed Second class in the three-class ships, who prefer Cabin accommodation because in no better class above them on the ship. The Cabin fares are only slighter higher than the Second class rates.

d) Second class retains its popularity, particularly on the 'monster' steamers.

e) Tourist Third Cabin is an entirely new class, and it is to this particular traffic thet the steamship lines look to take the place of the reduced emigration movement brought about by the US Quota Restrictions (United States Immigration Act, 1924). The Tourist Third Cabin quarters afford most comfortable accommodation to passengers to whom economy in travel is the primary consideration; and the development of this travel since 1925 shows clearly the possibilities of an increase in this movement of Americans desiring to visit Europe. Efforts are also being made to encourage the Tourist Third Cabin movement from Great Britain and Ireland to the United States, but it is expected that the bulk of this traffic will emanate from America.

f) Third class continues to be maintained more particularly for the emigrant type of passenger, and the worker in the United States or Canada when returning home on seasonal or occasional visits.”

3) Application of desel-electric motors as main power plant of ocean liners

Diesel engines with compression ignition (i.e. igniting the liquid fuel with the increase in temperature occurring during the mechanical compression of the air in the cylinder space) are the most efficient types of internal combustion engines due to the simplicity of their operating principle, as well as their size and fuel economy. The first commercial ship powered by a diesel engine was the Russian oil carrier VANDAL, launched in 1903, whose diesel-electric drive train enabled a shallow dive in contrast to the space requirements of earlier long-stroke piston steam engines, therefore, the ship could travel in the Volga River waterway system, from the Caspian Sea to the Baltic Sea. However, after their first use in 1903, marine diesel engines operated with a lower power/space ratio for several years, and only the appearance of turbocharging in 1907, which ensured higher power density, accelerated their spread, as they could now operate with greater efficiency than steam turbines. From 1911, the new power source was installed in submarines, and from 1912 in ocean liners. The first diesel-powered ocean liner was the Danish SELANDIA. The possible prospects of the development were discussed by several engineers, including Dr. Ernst Förster, the designer of the largest ships of the time, the LEVIATHAN (ex-VATERLAND) and the MAJESTIC (ex-BISMARCK), whose study entitled "Big and Fast Liners of the Future" was published on April 23, 1923 in a technical journal 'Scientific American'. Förster also analyzed the issues of the main dimensions and propulsion and came to an interesting conclusion, insofar as he saw the solution in increasing the height instead of the length and width, without increasing the draft, but the diesel propulsion was strangely not considered seriously and the steam turbines counted on its long-term survival as the main engine of large ocean liners:

„With respect to the modern and most economical design of turbines and boilers, as well as maximum passenger accommodation and maximum dimensions of the vessels, the Majestic and the Leviathan have to be regarded as marking the hight level of development in the North Atlantic trade, distinctly showing the extreme limit under present conditions in the way of further progress. The draught being almost 39 feet may not be increased for the next 10 or 15 years by much more than one foot, the draft being controlled by the depth of the main entrances to New York harbor as well as to Plymouth, Southampton and Cherbourg. The length of the biggest vessel being 954 feet over all, cannot reasonably be increased by any considerable amount; for it is limited by the present length of the piers in the North River. Furthermore, any increase in length, draft, and size will increase the difficulties of handling and navigation. Even stronger is the argument against much larger and aster ships on the grounds of economy.

[…] The most important technical question bearing on progress is that of the propelling machinery. The promising development o the internal-combustion engine (on the Diesel-principle) has in some quarters created illusions with respect to future possibilities, which, in the direction of Diesel reciprocating engines, do not appear to be based upon sufficient grounds. As to the gas turbine, there is nothing in the success so far achieved in experimental work to warrant the conclusion that this type can be applied for many years to come as a drive or large and fast Atlantic liners. However, the development of the geared steam turbine has reached a point where it would be possible to build a Mauretania, a Majestic, or a Leviathan that would show an economy of operation far superior to the existing vessels that carry those names. The saving in weight and space, as well as the smaller consumption of fuel oil on account of the far higher speed of revolution of the main turbines, has established, without any doubt, the wisdom and practicability of applying the geared drive to the big liners of the future.

Profiting by the advantages of the reduction gear, there are two diverging directions for future development: one aiming at a higher speed, the other economizing the management to the highest possible degree. In considering the question of higher speed, the question is, how far may this be carried; what will be the saving of time accomplished; and will this shortening of the passage justify the far greater cost of construction and operation? Adopting a maximum possible speed of 29.12 knots and an average ocean speed o 28.35 knots, we get the following results: On the Winter Course, the passage between Ambrose Channel and Cherbourg would be made in 4 days 15 hours; between Ambrose Channel and Plymouth in 4 days 13 hours. On the Summer Course the AMbrose Channel-Cherbourg course would be covered in 4 days 12 hours, and the Ambrose Channel-Plymouth course in 4 days 10 hours. Going eastward in summer time it may be desirable to leave New York for Plymouth (or Cherbourg) one, (or three) hours later, in order to utilize the day o departure as a whole working day. In this case the average speed would have to be increased to 28.6 or 29.12 miles an hour.”

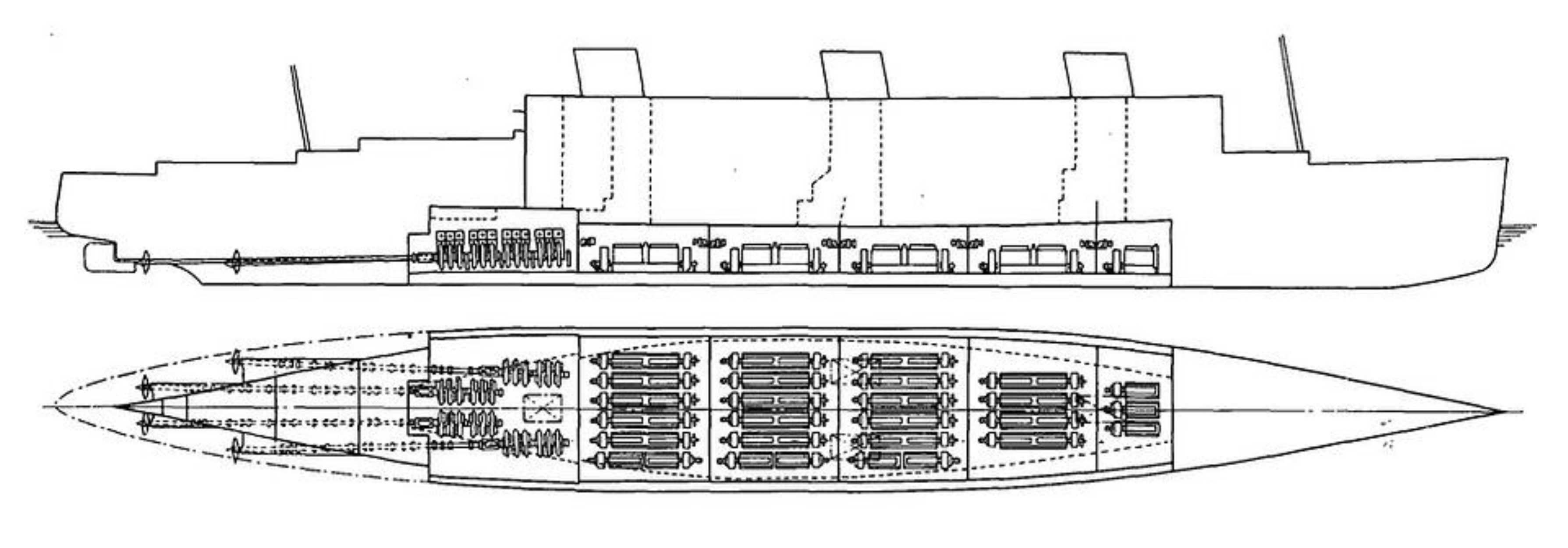

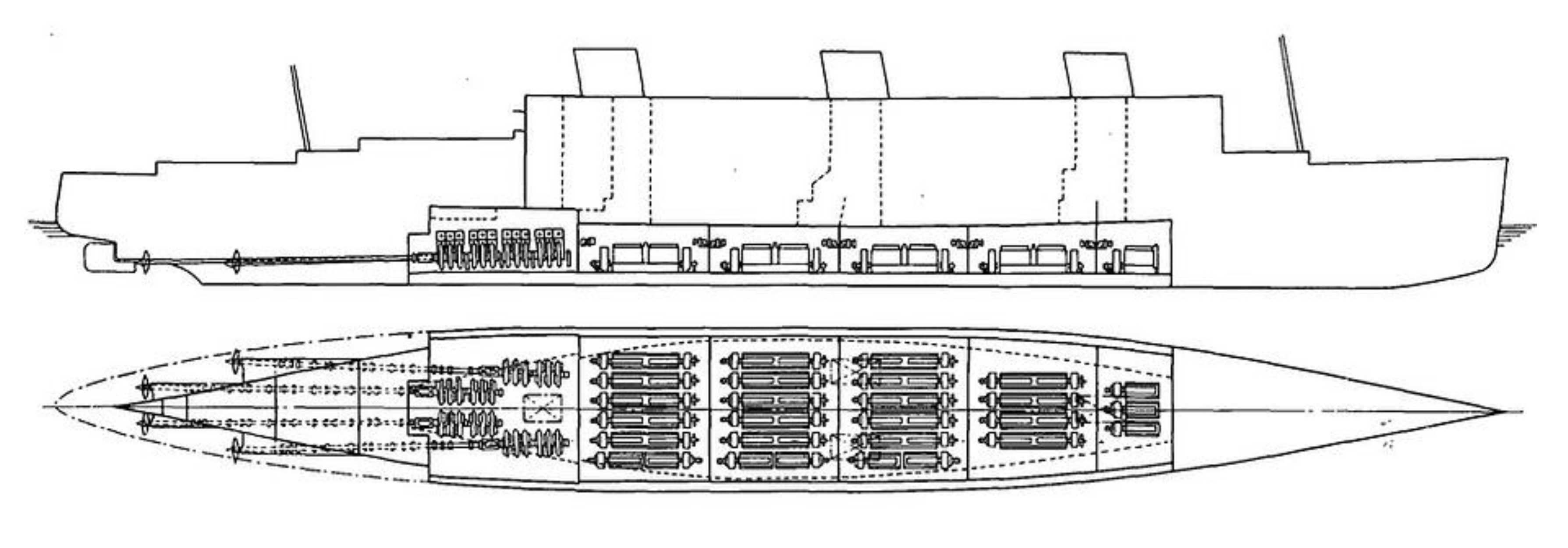

The article included a diagram showing the features of the planned "improved MAJESTIC".

Fig. 9: Design (top), cross-section (bottom left), side and top view of the boiler and engine room (bottom right) of the "improved MAJESTIC". Captions are as follows: “Above: Although the ship shown above would be of 6.900 tons less displacement and 11.000 less horsepower than the MAJESTIC, and would require 1.135 tons less oil each trip, she would carry 1.146 more passengers at the same sea speed of 23 knots. Bottom left: Midship section showing the bulges at the waterline, which afford sufficient stability to permit the use of one deck more for passengers (shown shaded) than there are in the MAJESTIC. By this means the passenger accommodation is raised from 3.100 in the MAJESTIC to 4.246 in the proposed ship, the speed (23 knots) being the same. Bottom right: Elevation showing engine and boiler rooms necessary to drive an enlarged MAJESTIC at 28.35 knots sustained sea speed. (For plan view see below). Plan view of the engine and boiler plant necessary to drive an enlarged MAJESTIC across the Atlantic at 28.35 knots. To supply steam for the turbines of 165.000 horsepower would require 64 water-tube boilers.” (Source: Scientific American)

Fig. 10: The arrangement of the superstructure in the "improved MAJESTIC", which at first seems unusual, is not without precedent. The White Star steamer CALGARIC, launched in 1917 at the Harland & Wolff Shipyard, had a similar one. (Source: Dr. Tamás Balogh)

IV.) Design-variants of the OCEANIC (III):

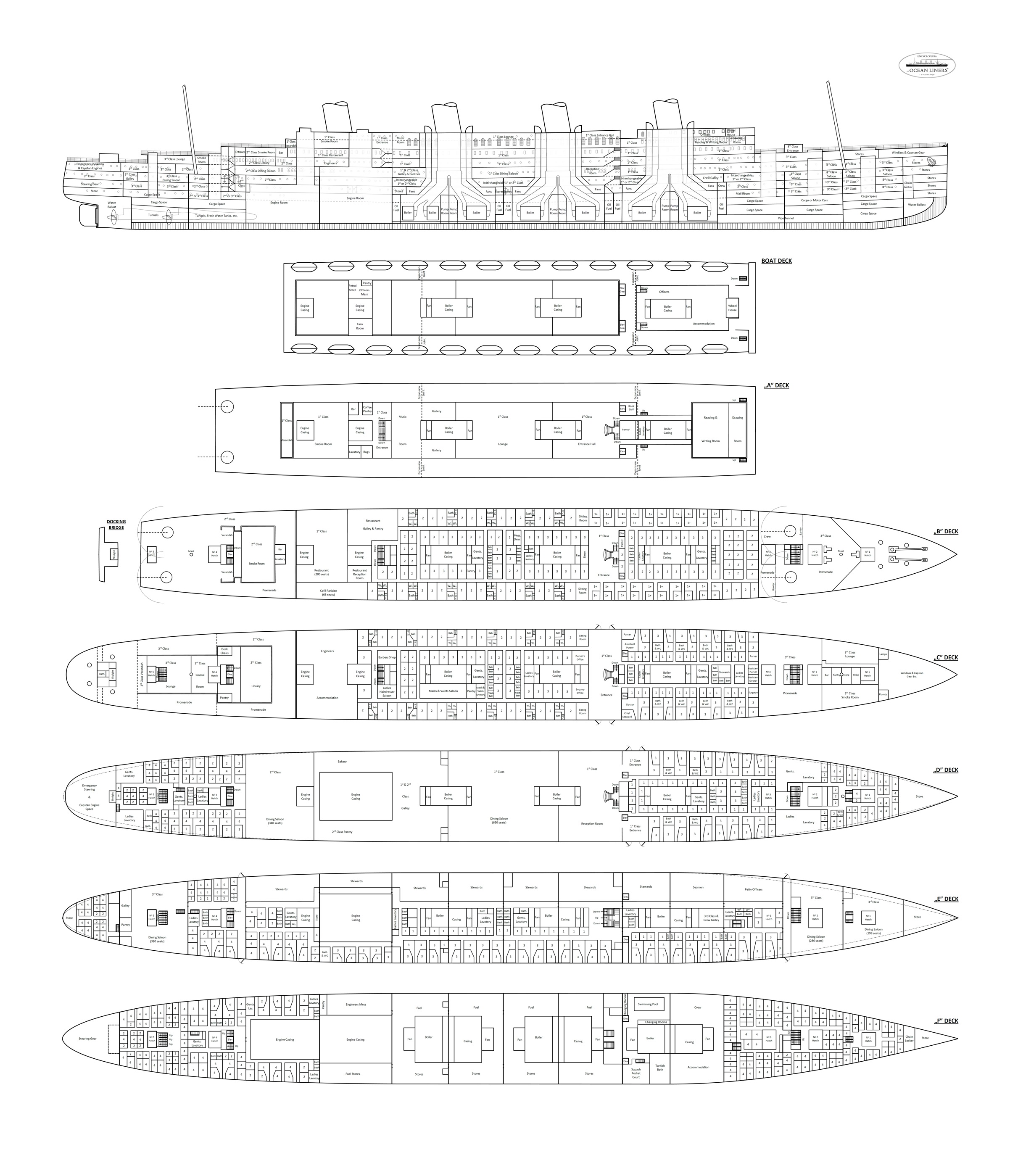

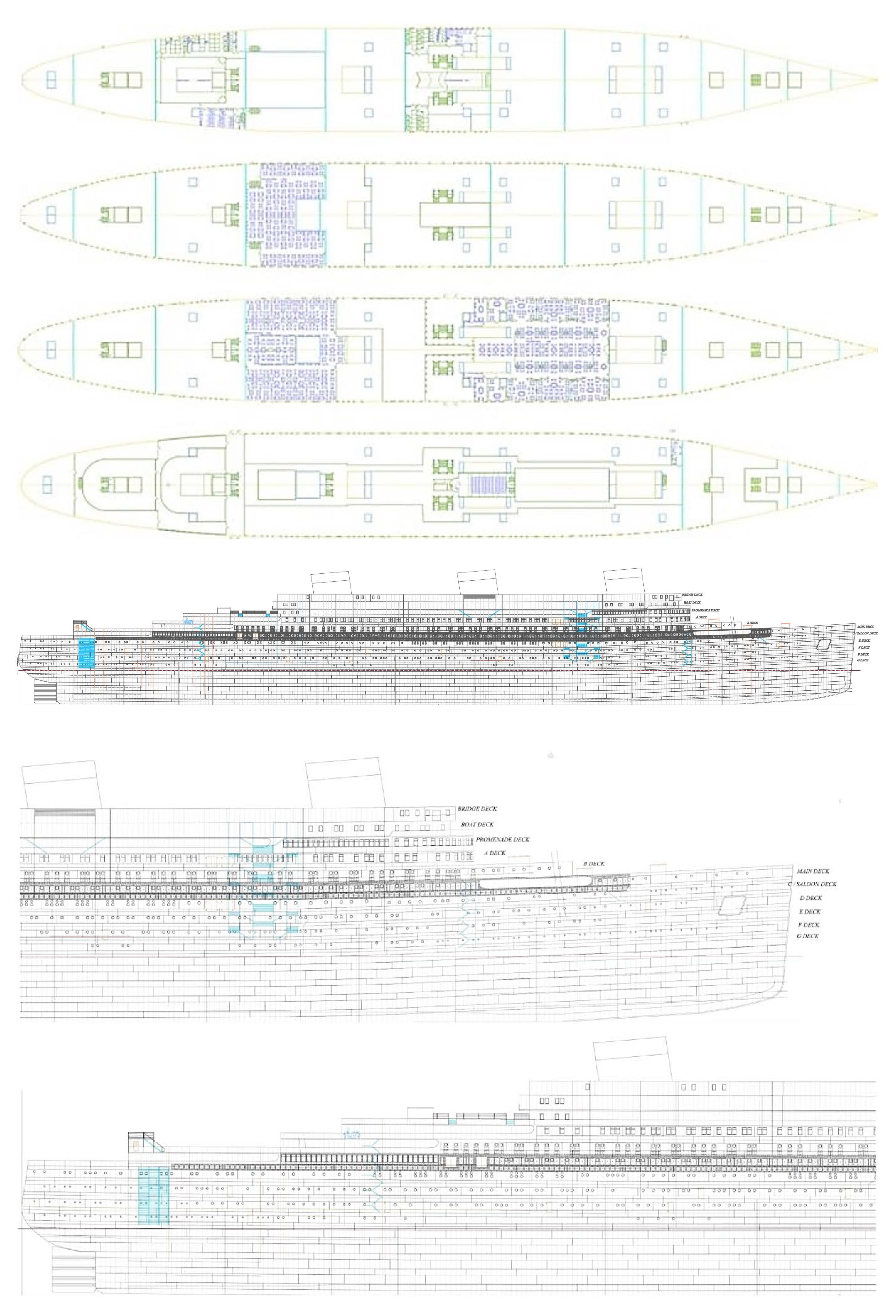

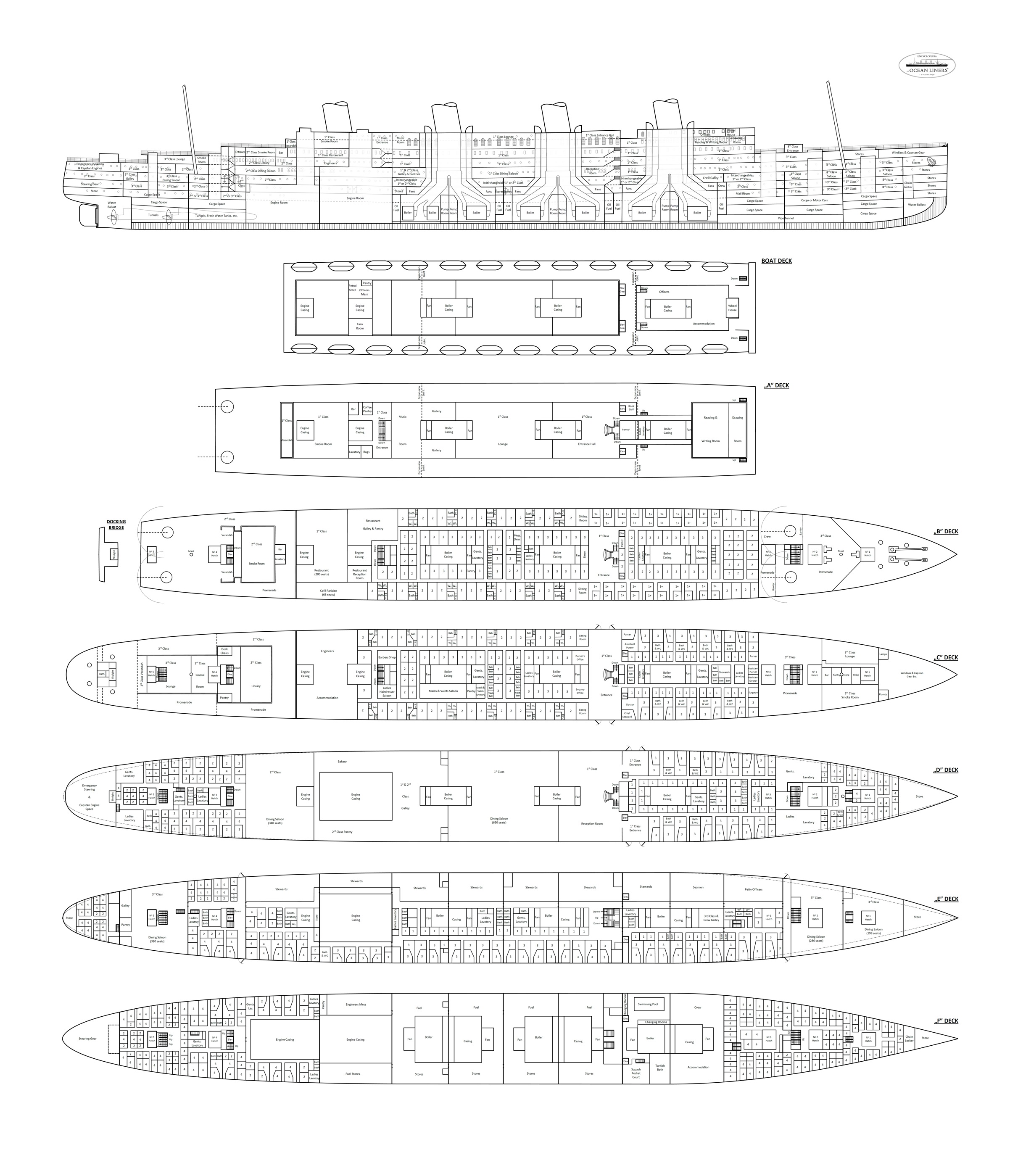

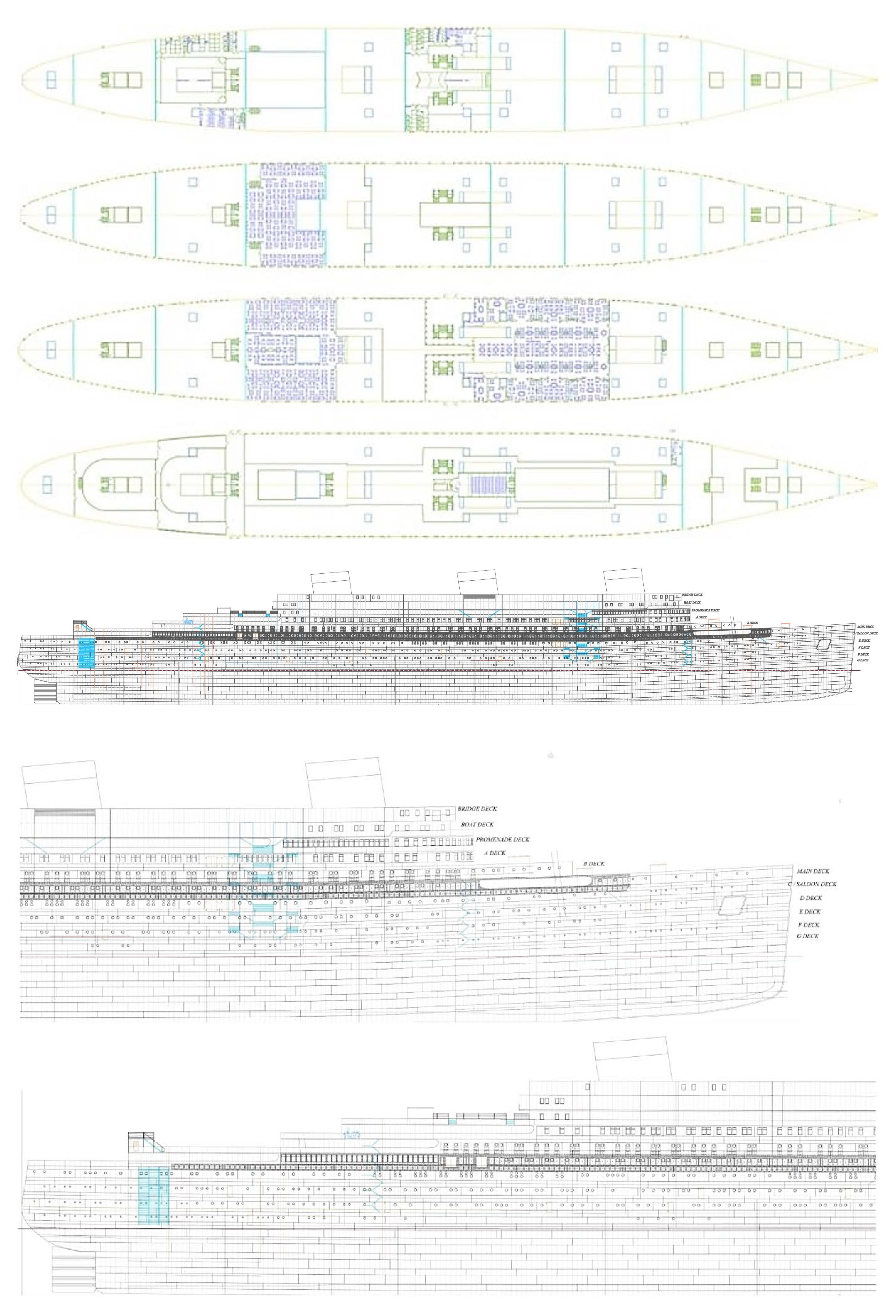

In June 1923, the still American-owned White Star Line asked Harland & Wolff to begin designing a new ship to replace the HOMERIC. However, due to US immigration restrictions in 1924, Harold Sanderson, Chairman of the IMMC Board of Directors, withdrew from the investment. In August 1925, following the introduction and acceptance of tourist class, the White Star Line requested a new offer from Harland & Wolff. Following this, the shipyard prepared several sets of plans[2] for the company between 1926 and 1928, which wanted to name the new ocean liner after OCEANIC (I) built in 1871 – the very first ship of the company – and OCEANIC (II) built in 1899. Both ships were harbingers of great changes: the first OCEANIC introduced the hull form with an almost square cross-section in the middle, which later became common at White Star Line, and the second OCEANIC introduced the corporate business policy of prioritizing comfort over speed. From the third OCEANIC by comparison they expected a rebirth after the great losses – the TITANIC disaster and the World War. The OCEANIC (III) was partially built between 1928-1929, but finally she remained unfinished and her completed parts were dismantled. If completed, she would have been the world's first ocean-going passenger ship longer than 1,000 feet (300 m) and, until 2004 - the launch of the QUEEN MARY 2 - the largest diesel-electric powered ocean liner (moreover, she could have claimed the title of the most powerful diesel-electric powered ship to date).

Of the several plans that were completed, the drawings of only three have surfaced, to varying degrees.

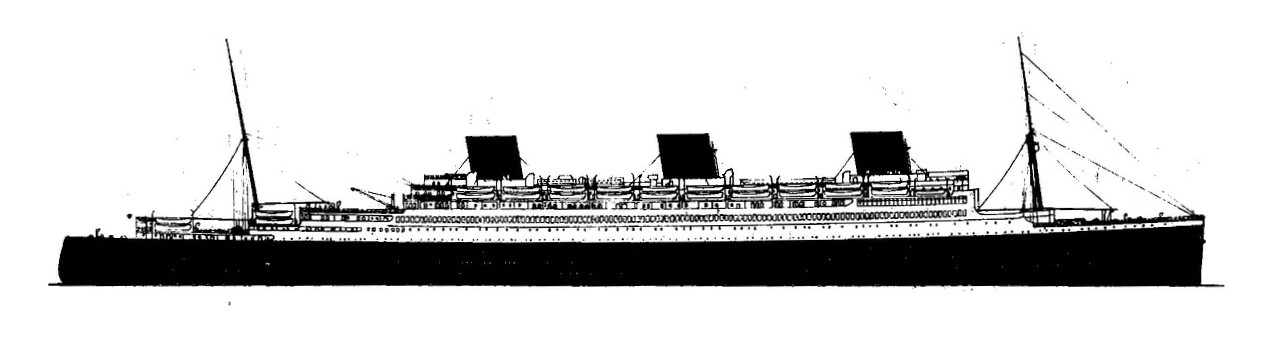

The first among them was completed on January 28, 1926. This first version of the design featured only a conventional steam-powered, 904-foot (276 m) long, four-stacker ocean liner (essentially a fourth OLYMPIC-class ship) that deviated from the traditional WSL outlines in only one respect: she got the so-called "cruiser stern", which was already common in the design of the 1920s. German engineer Jochann Schütte already proposed the use of this stern-shape - typical of cruisers - in 1900, during the design of the german greyhound KAISER WILHELM II., but the first ocean liner with a cruiser stern, the ALSATIAN, was only built in 1913. In any case, Harland & Wolff used this structural element on its ocean liners since the launching of BELGENLAND (1914) and WINDSOR CASTLE (1921) due to its beneficial properties (increasing the waterline length affecting stability and speed and the deck surfaces that can be used for accommodating passengers).

Apart from that, the number and arrangement of the ship's decks - the whole appearance of the ship in general terms - basically reflected to the OLYMPIC class (as far as can be judged from the surviving partial documentation). However, compared to the TITANIC, which was considered as a model for the design, some things have still changed:

Fig. 11: RMS WINDSOR CASTLE, the ship used as a starting point for the concept design (the RMS OLYMPIC shown in the background). (Source: Wikipedia)

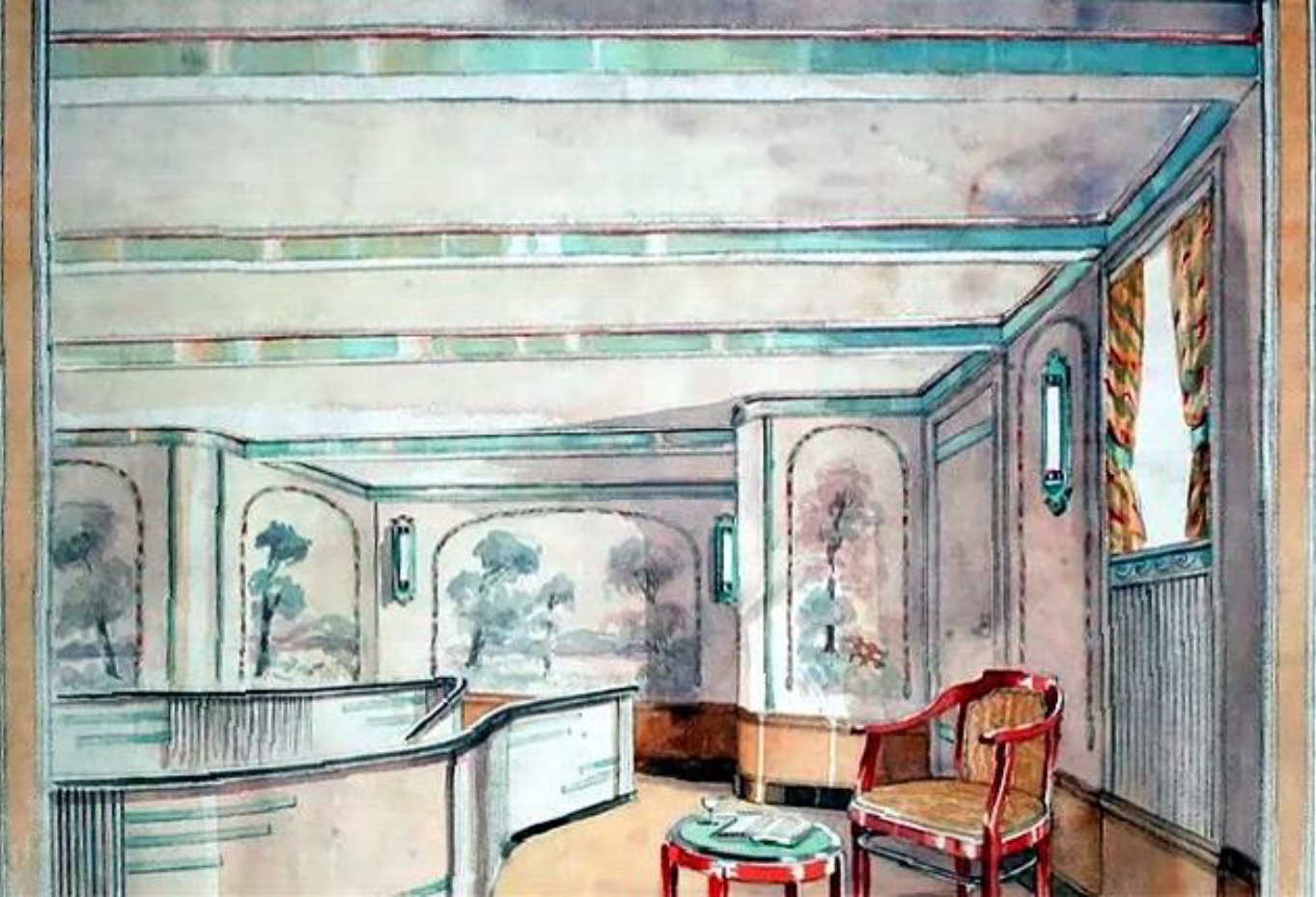

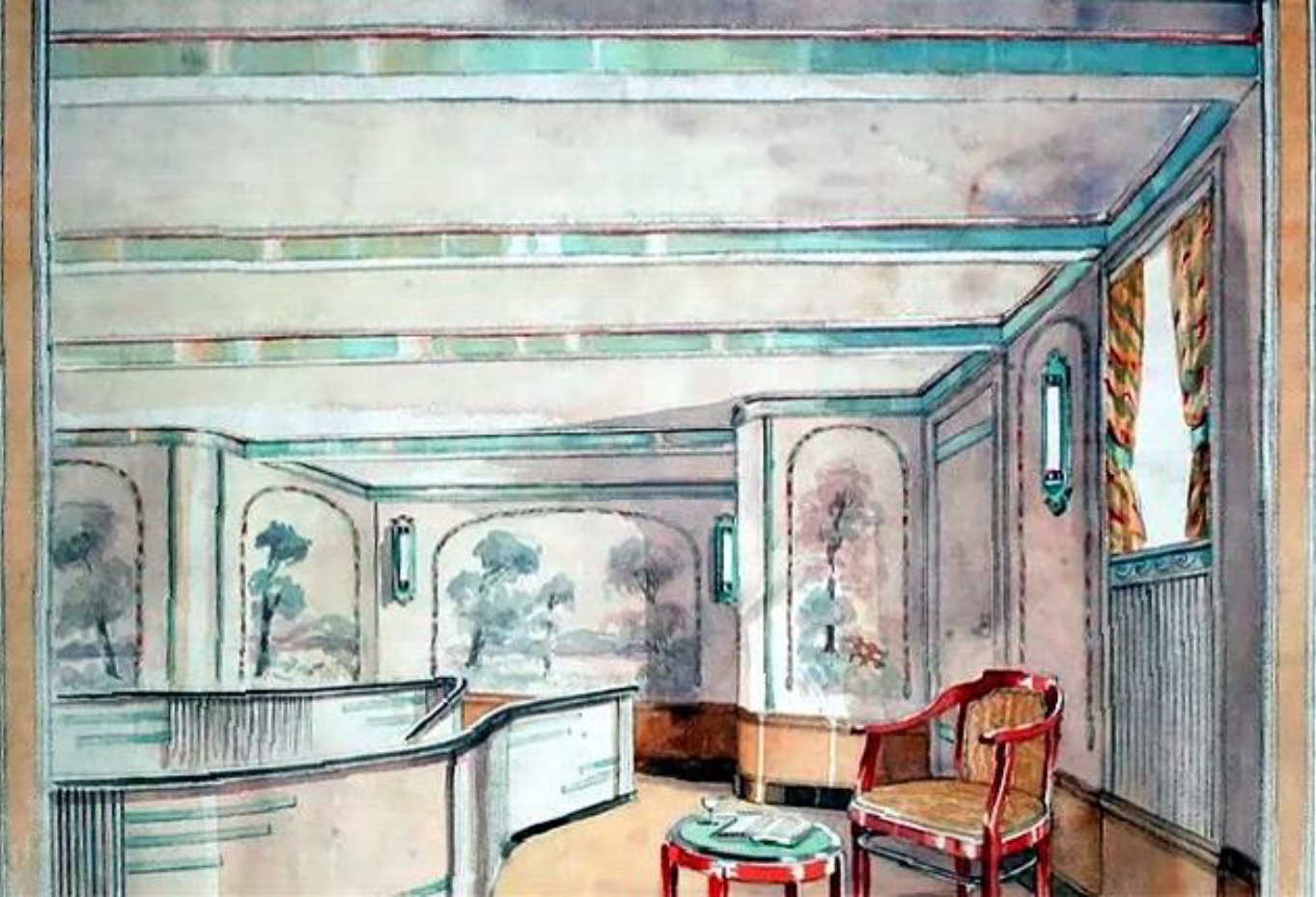

First of all, the front end of the superstructure was changed following the angular form of British Art Deco villa architecture (the curved parapet on wings of the navigating bridge on OLYMPIC and TITANIC was replaced by a more simple parapet, similar to that was used in WINDSOR CASTLE which was completely straight and flat rom top view). The glass-enclosed section of the forward end of the "A" deck first-class promenade was shortened on the model of WINDSOR CASTLE (this design-element derived from the plans of the unfinished liner NEDERLAND of 1914), and most of the deck was thus occupied by the open promenade. Only at the aft end of the "B" deck was a larger, open promenade created for the second class and a glass-closed one for the first class passengers on the territory belonged to the Café Parisien. On deck "C" in the front (where the forward well deck had been situated on the TITANIC) an open promenade was designed for the third class, while at the end of the ship, a glass-enclosed promenade was created for the second- and behind that an open promenade for the third class passengers.

The planned passenger-carrying capacity of the ship was 792 in first class, 380 in second class, and 1,240 in third class, but there were also 326 berths in first class that could be used both for the first or for the second class, and 318 berths in second class that could be used both for the first or for the third-class, and with 126 berths that could be sold as second- or as third-class berths when needed. All in all, the number of places was sufficient for 2,066 people. The plan of the first-class suites was generally similar to the arrangement of the first-class suites on board of the OLYMPIC (decks B and C would have been occupied by luxury suites in the same way as on the TITANIC and on the OLYMPIC after she was transformed due to the loss of the TITANIC). Perhaps that is why Philip Albright Small Franklin - the president of the IMMC - mentioned in the first public communication about the start of the design work, in August 1926, that "The White Star Line is considering the construction of a gigantic ocean liner with a speed of 25 knots to replace the HOMERIC. The new ship will be superior and will have the best qualities of MAJESTIC and OLYMPIC and will show a family resemblance to the latter.” However, at the time of this announcement, new preliminary plans for the ship were ready...

Fig. 12: The first known concept design of OCEANIC (III) (below), and the sample ships BELGENLAND (above) and WINDSOR CASTLE (middle). (Drawings: Dr. Tamás Balogh)

Fig. 13: General arrangement drawing of the first known concept design of OCEANIC (III). (Drawing: Dr. Balogh Tamás, on the basis of the original plans, publiched by the TITANIC Historical Society)

Fig. 14: Profile and longitudinal section of the first remained proposal made for the OCEANIC (III). (Drawing: Dr. Tamás Balogh

Such a reconstruction is an ideal tool to better understand certain elements of the ship's design. With the help of this, it also turns out, for example, that some parts of the plan come from other, earlier ships.

1) The appearance of the ship (hull shape, superstructure design, number of masts and funnels) is an improved version of the OLYMPIC class - OLYMPIC, TITANIC and BRITANNIC.

2) The proportion of the glass-enclosed and open part of the upper promenade on the "A" deck (below the boat deck) and the cruiser stern (which had not been used on White Star Line's superliners until then) are clearly comes from the plans of the NEDERLAND and the ARUNDEL CASTLE, both designed by the Harland & Wolff Shipyard on the basis of the TITANIC.

3) The general arrangement of the interior spaces - the "floor plan" - comes from two sources: On the one hand, the designers adopted several elements of the OLYMPIC-class (e.g. the Café Parisien and the a la carte restaurant on deck "B", or the 1st class dining saloon and reception room on deck "D", the location and size of which are exactly the same as their prototypes designed for TITANIC). On the other hand, the HOMERIC (ex-COLUMBUS), which was taken over from the Germans as war-reparation, was also one of the ships taken into account in the design, insofar as this ship provided the model for the design of the two-deck high public spaces of the "A" deck (the maximum headroom on White Star Line's ships was only one and a half decks, but HOMERIC's spacious interiors proved to be very popular).

4) At the same time, the reconstruction above reveals that the main characteristics of the planned ship not only reflects the shape of other ships built earlier, but also introduced innovations that later gave an inspiration for the designers of other ships: The terraced-design of the aft end of the superstructure and the cruise stern, as well the cabs placed on the wing's ends of the navigation bridge, for example, later reappeared on the designs of the QUEEN MARY.

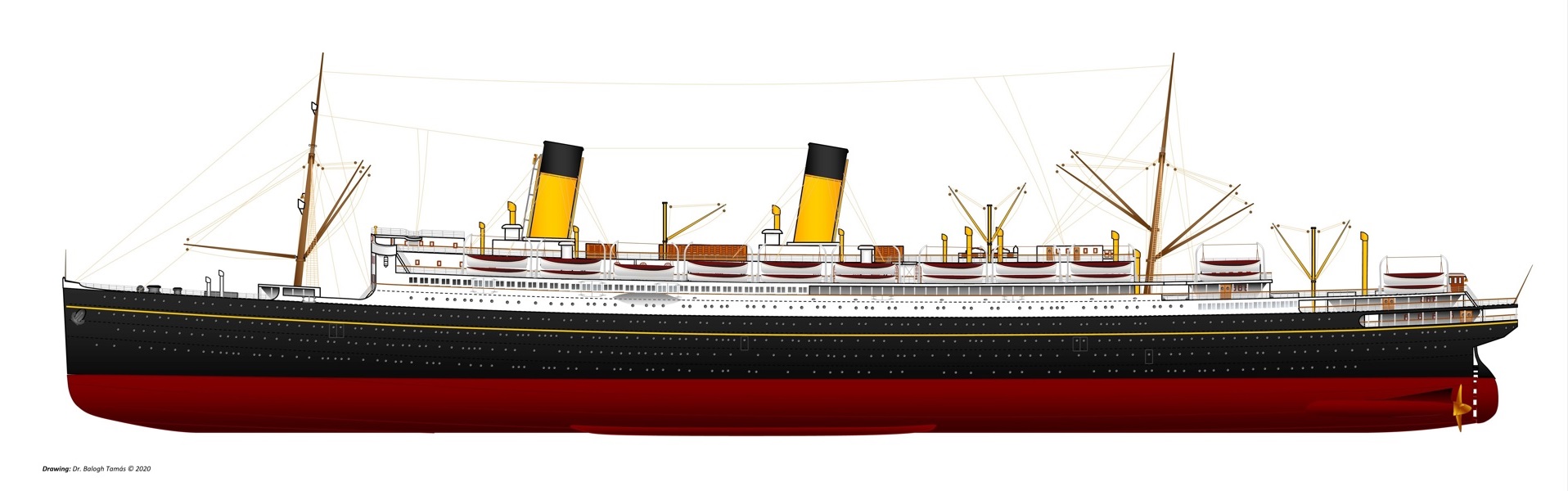

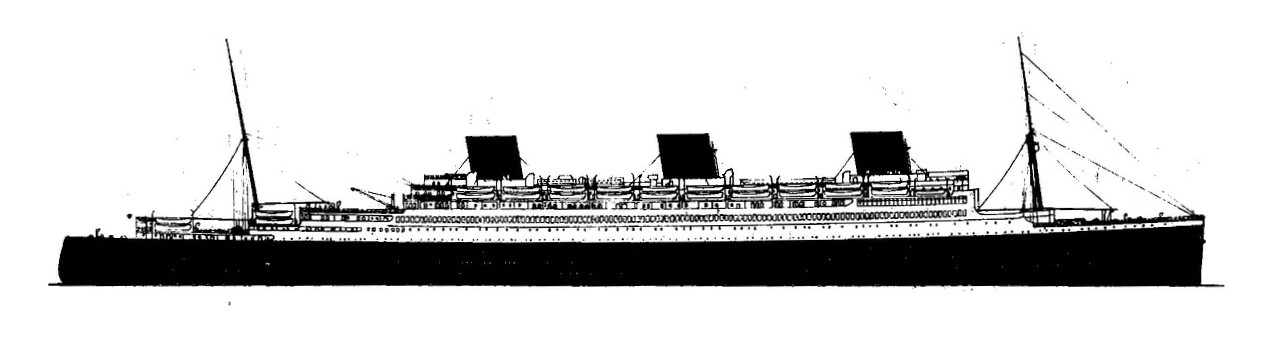

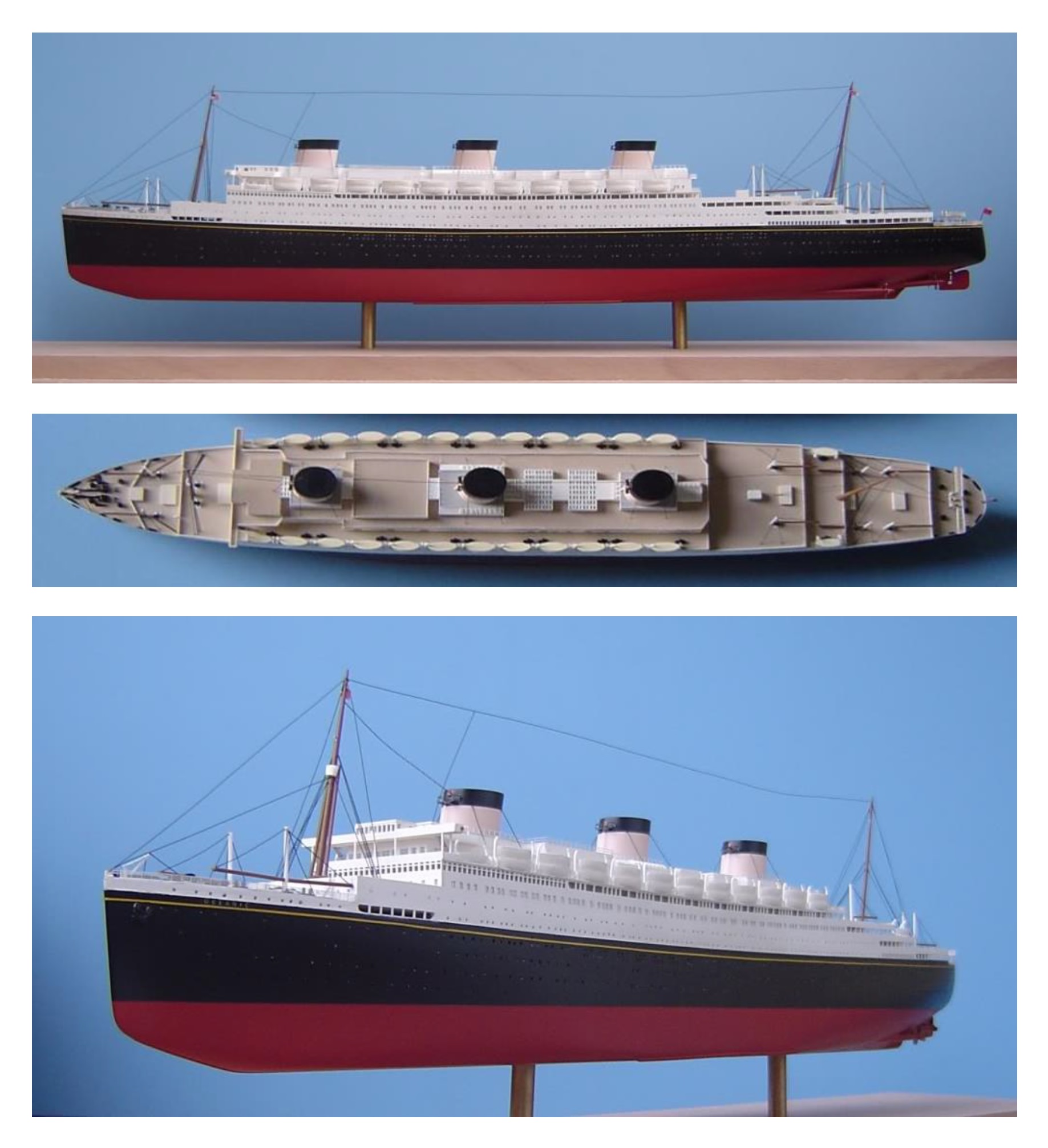

The second set of the plans which can still be known today, dated 9 March 1926, shows a 935-foot (285 m) long, 52,000 BRT three-stacker ocean liner, also built with a cruiser stern, roughly the size of the later German BREMEN and EUROPA. This ship has already differed significantly from the previous design in several points, and adopted more of the structural solutions used in the case of MAJESTIC (II) – the former German BISMARCK: for example, used split funnel uptakes, and the interior height of the large communal rooms in the boat deck superstructures reached 13 feet (4 m). The height of the hull from the keel to the bridge is 105 feet (32 m). Ship designers clearly aimed to create a modern exterior (the front view of her superstructure, for example, is clearly reminiscent of the facade of Villa Stein, also designed by Le Corbusier in 1926).

Fig. 15: Model of the ship made by Richard D. Edwards in 2006 based on the second known preliminary design of OCEANIC (III) (M=1:350).

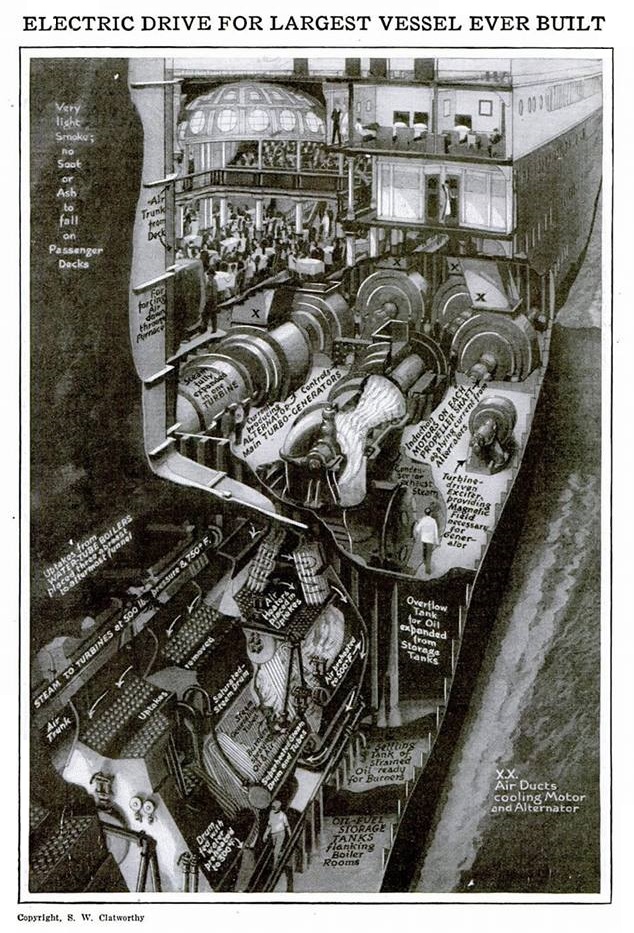

The general arrangement of the hull and the design of the superstructures were essentially the same as the previous design version, since the only significant modification was the relocation of the navigating bridge from the boat deck to the top of the officers' quarter, as well as the shortening of the "A" deck promenade and the moving of the mainmast forward. The fundamental difference between the second version of the design and the first one, lay in the propulsion of the ship, in that the combined system of piston steam engines and low-pressure steam turbine was planned to be replaced by a turboelectric drive system on the new ship, which is clearly indicated by the characteristic three, large-diameter, squat funnels.

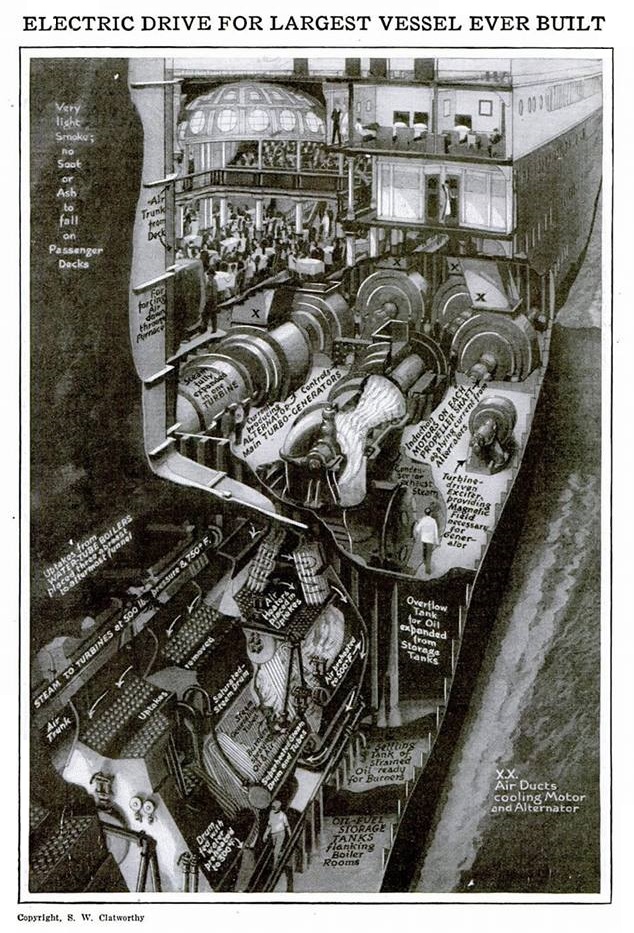

The combination of diesel engines and electric motors enabled a more flexible distribution of the machines inside the ship and, thanks to the flexible axle connections, considerably dampened the significant vibrations that had been continuously occurring until then, while moving forward at a high speed. Another version of the electric drive chain is the turboelectric drive, in which steam turbines are used to drive electric generators, and they convert the kinetic energy into electrical energy, which is then used to drive the electric motors that turn the ship's propellers. The extraordinary advantage of this solution is the safe connection (without complicated gearboxes) between the fast-rotating main engines and the slow-rotating propeller shaft in the water, as well as the operation of all the other electrical systems of the ship without a separate power generator. Frank V. Smith, an employee of the Federal and Shipping Department of the American General Electric company, summarizes the technical novelty of this in terms of the design of the OCEANIC (III) in the January 1929 issue of the technical journal "Pacific Marine Review", in an article describing the propulsion system of the American ocean liner VIRGINIA:

„High-speed, modern transportation is still of the utmost commercial and competitive importance in the seeking of mail contracts, the dispatch of valuable cargo, and in catering to first- class passenger traffic, and means are now being sought to increase again the power and speed of ships. In 1913. United States naval engineers, in cooperation with W. R. L. Emmet, consulting engineer of the General Electric Company, saw the tremendous advantage which electric propelling equipment would have for ships. Through their concerted efforts this type of propulsion was tried out on the collier Jupiter as an experiment. It was an unqualified success—so much so, in fact, that all of the later battleships were so equipped.

Our great background of electrical experience now stands us in good stead; we have a power in our hands which can be carried to any limit desired. Electric drive was installed on the airplane carriers Saratoga and Lexington, and, in a recent trial, the latter developed the unprecedented power of 210,000 horsepower at the propeller shafts; this amounts to 262 per cent of the greatest power ever applied on a North Atlantic liner and 131 per cent that which had ever been applied to a naval vessel of any type whatsoever. Our merchant marine was slow to adopt this new form of drive, until in 1926 the International Mercantile Marine Company, with great vision into the future, decided to build three electric liners for its Panama Pacific Line. This company had the utmost confidence that such a project would stimulate trade between the east and west, and that the traveling public would give its unanimous support to ships that provided both speed and the ultimate in comfort to its passengers.

The steamship California was a brilliant success, and in its one year of service has become one of the most popular ships afloat. Its passenger accommodations have been booked ahead for as much as five months. Its economies usher- ed in a new era in ship propelling machinery' which made it possible to give high speed service at reasonable rates. The fuel rate was but from 60 to 70 per cent of that existing on the large ships of the North Atlantic. The eyes of Europe were turned westward, and the far-reaching effect of the California's performance can hardly yet be fully visualized. The Peninsular & Oriental Line contracted for the building of a similar ship for its India and Australia trade route; this ship, named the Viceroy of India, is now nearing completion, and will soon be placed in service, Lord Kylsant recently announced that the new 1000-foot passenger liner now being built by the White Star Line is to be electrically driven. Other European lines are also thoroughly investigating the new possibilities which have been opened up because of the unlimited and economical power which can now be produced electrically on ships.”

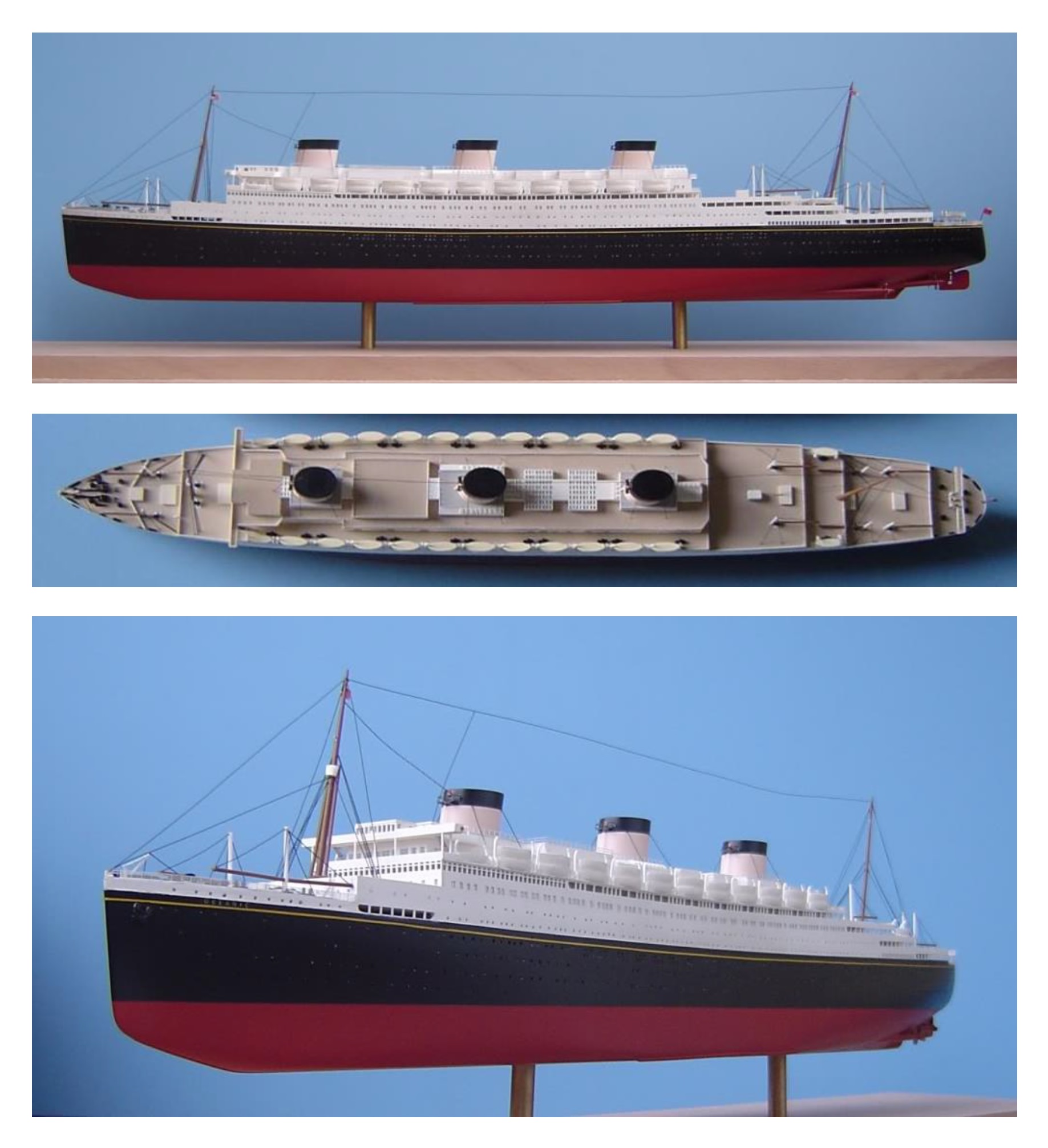

Fig. 16: Contemporary depiction of the OCEANIC (III) turboelectric propulsion system in the Popular Mechanics Magazine by S. W. Clatworthy (Source: Research by Eric Okanume). The caption to the picture was as follows:

„Giant liner to be driven by electric motors – When the White Star Line puts its first big post-war liner into service, it will be not only the biggest ship ever built - 1.050 feet in length and displacing 60.000 tons - but also the biggest electric-driven ship. This type of drive, pioneered by the American navy in battleships some years ago, has been applied to the 17.000-ton liner California and the Virginia, now building, both under the American flag, and in the new 19.000-ton P & O liner Viceroy of India, recently launched in England. The White Star ship, on which work has been started at Belfast, will have four boiler rooms, the aftermost of which is shown in the foreground of the artist's drawing. Oil fuel, with automatic firing, will be used. High-pressure water-tube boilers will be fitted with forced draft of supreheated combustion air. In the main engine room, seen beyond the boiler room, the steam will drive turbo-generators at about 3.000 revolution per minute to generate the electricity for the driving motors, directly connected to the propeller shafts and revolving at about 100 revolutions per minute. The electric drive has many advantages, including ease in maneuvering, quickness of reversing power, and the fact that the propellers cannot race when thrown clear in heavy seas.”

The performance achieved with turboelectric propulsion is typical of the fact that the American aircraft carrier LEXINGTON, mentioned in the quoted article of the Pacific Marine Review, after its launch in 1925 and commissioning in 1927, in the turn of 1929-1930 - for almost a month - supplied the city of Tacoma in Washington State with electricity. During the dry summer of 1929, the western part of the state was drought-stricken, resulting in low water levels at the first dam of Lake Cushman. Since the hydroelectric plant there was the city's primary source of energy, but by December the water level had dropped below the dam's intakes, the city asked for help from the United States federal government, which sent the LEXINGTON to the scene, where the ship's engines - the 4 4 47,200 HP (35,200 KW) generators feeding a 22,500 HP (16,800 KW) electric motor were connected to the city's power grid. The generators provided a total of 4,520,960 kilowatt-hours between December 17, 1929 and January 16, 1930, until melting snow and rain raised the reservoir's water again to a level sufficient to provide the city's entire electrical power supply. This case was an excellent demonstration of the potential of turboelectric propulsion. Although this example was not yet known at the time the OCEANIC (III.) was designed, the propulsion system of the new British ocean liner was modified to introduce turboelectric propulsion, and this change was clearly influenced by the Americans.

However, the implementation of the plans was forced to be suspended in the fall of 1926, when Harland & Wolff's supply of raw materials suffered a serious shortage, and when Lord Kylsant bought the White Star Line from IMMC in November of that year. Kylsant was the champion of (diesel and turbo) electric propulsion in Great Britain, since until then only shipping companies belonging to the interests of Royal Mail Lines built ships with such a drive chain in Great Britain. Since 1920, Harland & Wolff has gained experience in building various motor ships (their first diesel ship was the freighter GLENOGLE built for the Glen Line, launched on 15 April 1920 at Govan, near Glasgow, and their first diesel ocean liner was the Royal Mail Lines ASTURIAS (II.) built for ocean liner launched on 15 Sep 1928 at Alexander Stephen and Son's Shipyard in Glasgow). For OCEANIC (III), Kylsant therefore proposed a diesel-electric drive train instead of the American turbo-electric technology, which presents a fundamentally new design and production challenge.

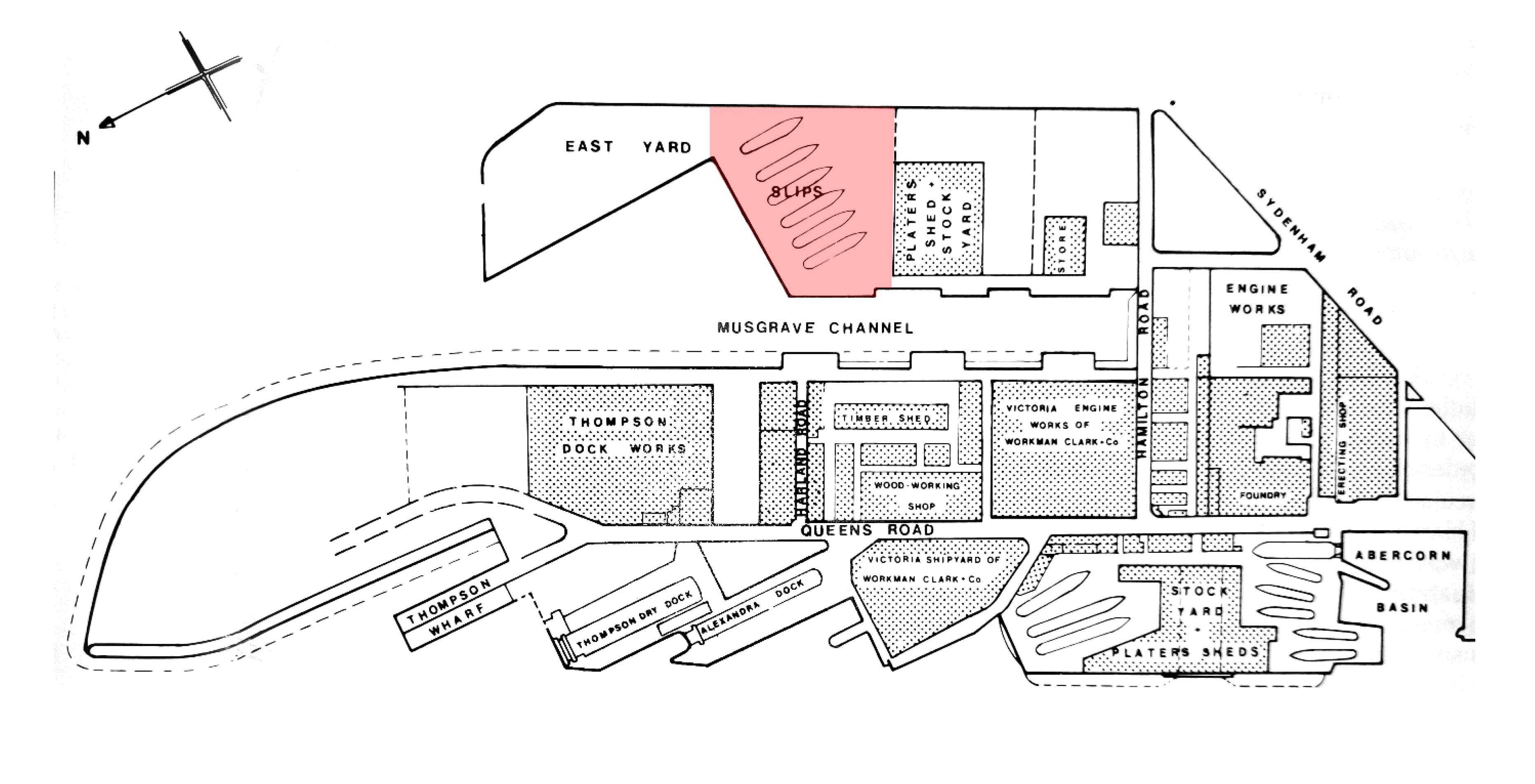

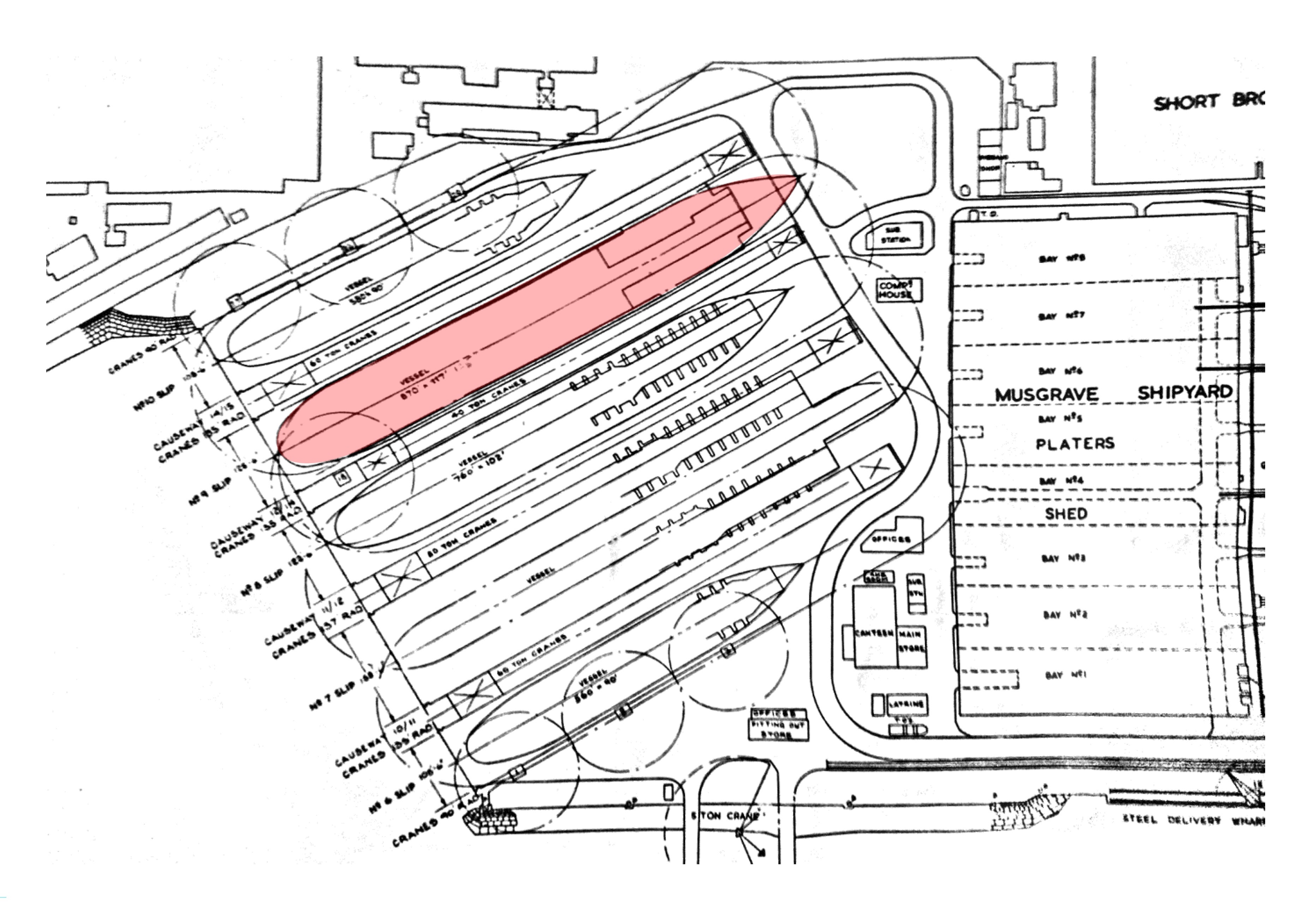

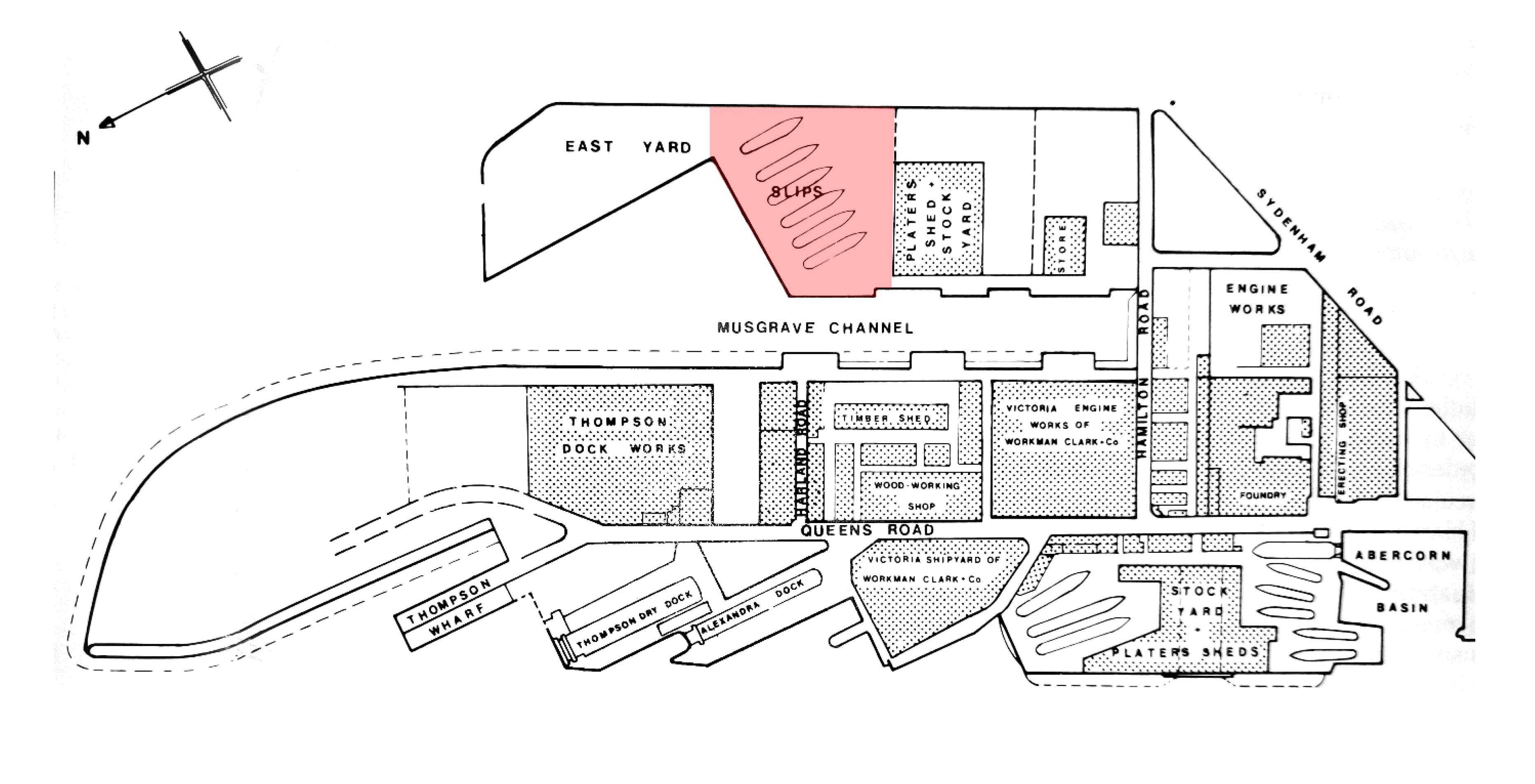

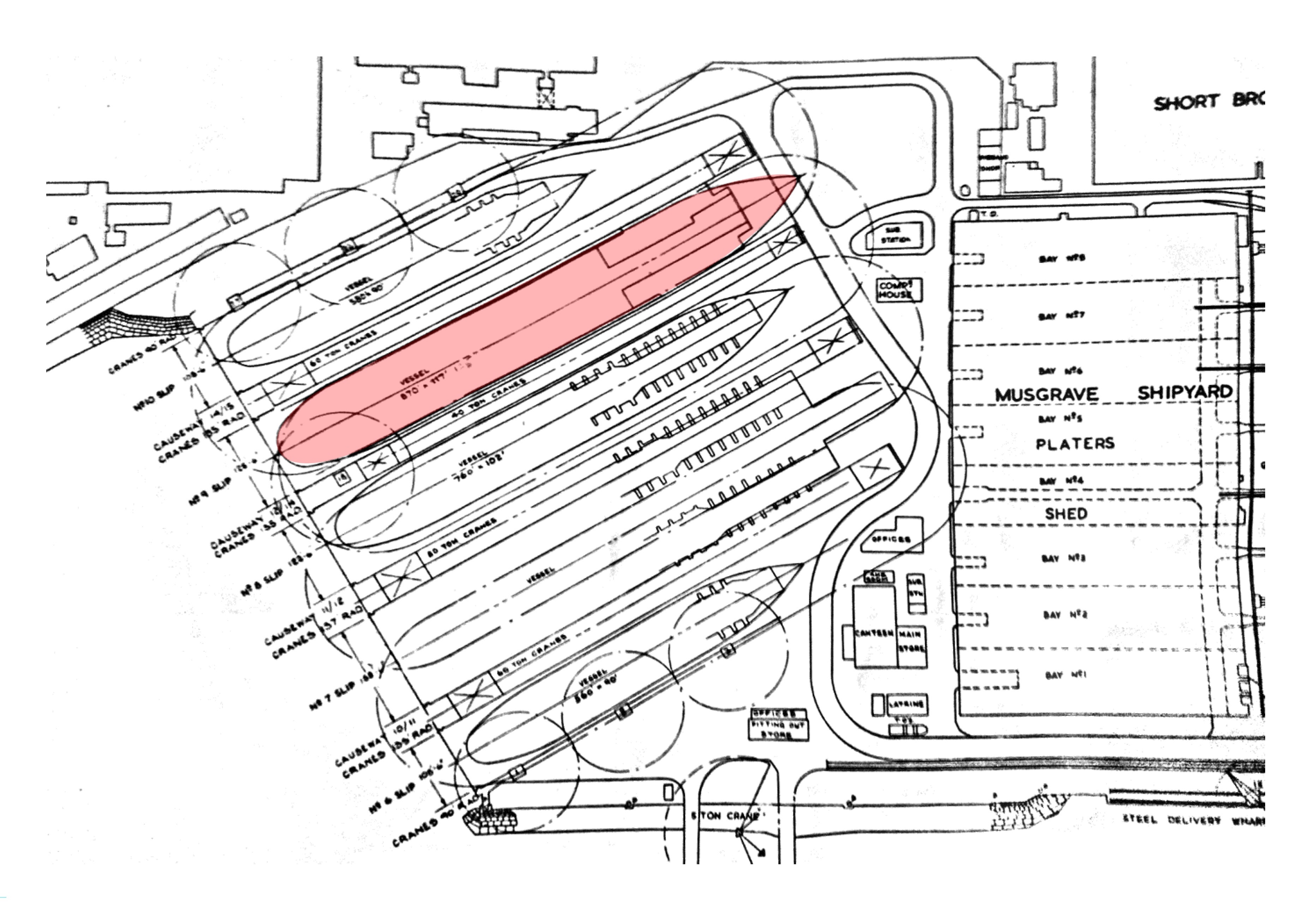

Kylsant also changed the main dimensions of the ship: he added a deck to its height (which increased the tonnage from 60,000 to 65,000 tons), and he also increased its length, although regarding the exact dimensions of the ship - as the final shipyard blueprints and the builders model were lost - only estimates, oral communications, and recollections are known (the shipyard had to be remodeled in any case, just as it was before the construction of the OLYMPIC-class). C.J. Slater, an employee of Harland & Wolff, who began his career as an architect and civil engineer in 1928 (taking over from his father, who was a consulting civil engineer at the factory), later wrote that he was the "innocent junior" to whom the abolition of labor was entrusted after the decision to dismantle the finished parts of the ship was made. Prior to the laying of the ship's keel, he was also responsible for the extension of slipway 14 established at Harland & Wolff's new, northern building site, the so-called Musgrave yard. This extension alone consisted of driving more than 1,000 40- to 60-foot piles, each 15 inches in diameter, and reinforcing ("wrapping") the pre-existing concrete piles. In his memoirs, he states that "the contours of the ship were always marked as 1,001 feet long on drawing of the slipway." However, some sources (such as the author of the article cited in Figure 13) mention a total length of 1,050 feet.

The concepts of length between perpendiculars (LBP) and length over all (LOA) must be clarified here. The length between the perpendiculars is the value of the distance between the vertical stern post (column in front of the rudder) and the stem (column between the keel and the upper deck, erected at the very forward end of the hull). Compared to this, the total length is the value of the distance between the farthest points of the structural elements extending beyond the bow and stern (the tip of the bow that leans forward and the stern that bends over the rudder).

Fig. 17: The construction site of the OCEANIC (III), at Harland & Wolff's northeastern (Musgrave) yard, which was expanded in the 1920s.

Fig. 18: The original slipway No 9. – after the expansion, slipway No 14. – on which the keel of the OCEANIC (III) was laid. Since the ship would not have been able to dock in the available docks, the construction of a 1,500-foot (460 m) long dry dock was started on March 24, 1928, simultaneously with the preparation of the construction site.

On later large liners of the era, the difference between LBP and LOA ranged from 40 to 70 feet. For the French NORMANDIE, the overall length was 1,029 ft (313.6 m), the length between the perpendiculars was 962 ft (293.2 m) (67 ft - 20.5 m - the overhang), and for the QUEEN MARY LOA 1 019 (310.7 m) to LBP 975 (294.1 m) with an overhang of 44 ft (13.4 m). Based on this, it cannot be ruled out that OCEANIC (III)'s planned length between perpendiculars of 1,001 feet (306.3 m) was accompanied by an overall length of 1,050 feet (320 m), while its width was 120 feet (36.6 m), its draft and was determined to be 38 feet (11.6 m).

Fig. 19: Artist's rendition of OCEANIC (III), as seen on the cover of the book "Damned by Destiny", from 1982. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The third version of the plans to resurface - dated from 1927 and finally accepted by the White Star Line - accordingly shows a giant of 80,000 GRT built with three squat funnels and a cruiser stern, with a height of 144 feet (44 m) from the keel to the bridge. Unfortunately, the information has remained about this design is the least detailed.

Fig. 20: Princess Mary - the only daughter of King George V and Queen Mary - visits the keel of OCEANIC (III) in the Harland & Wolff Shipyard, in October 1928. This is the only known surviving photographic representation of the ship. (Source: British Pathé, 746.22)

The White Star Line ordered the ship on June 18, 1928, and the keel was laid ten days later. It is typical of the level of public interest surrounding the event that even the heir to the throne visited the Motherwell Steel Works, the manufacturer of the ship's keel plates, where he took part in the producing of one of the them. However, work soon slowed as OCEANIC's propulsion system had to be completely redesigned again, this time with performance in mind. The frenzy for size and speed that revived after the First World War necessarily led to an increase in the performance of ship machines: after all, the White Star Line wanted to build not only the largest but also the fastest ship in the world with the new OCEANIC, when it decided to recapture the Blue Ribbon lost in 1892. While at first it seemed that it would be enough "only" to break the MAURETANIA's speed record of 26.06 knots (48.26 km/h) set in 1909, for which a sustained speed of at least 27, but even more 30 knots (50-55 km/h ) needed to maintain speed, until the time of the keel laying of OCEANIC (III), the situation changed, as new rivals appeared on the horizon: In 1926, Cunard Line announced its brand new ocean liner to replace the AQUITANIA built in 1913 - the later QUEEN MARY – the beginning of its design, while in France they started to design a new mammoth ocean liner, the later NORMANDIE, capable of surpassing all previous competitors. In addition, it was already under construction in Germany since June 18, 1927, and were launched on August 15 and 16, 1928, the pair of ships EUROPA and BREMEN, which were also constructed to win the Blue Ribbon. Construction was therefore suspended on 23 July 1929, immediately after BREMEN had captured the Blue Ribbon from MAURETANIA on 16 July at a speed of 27.83 knots (51.54 km/h), as it became apparent that OCEANIC (III), knowing the new developments, it is necessary to design a machinery that provides really convincing performance, which was made difficult by the fact that the main dimensions of the ship had previously been considerably increased.